Haley Miller

Waco High School

Individual Performance

Senior Division

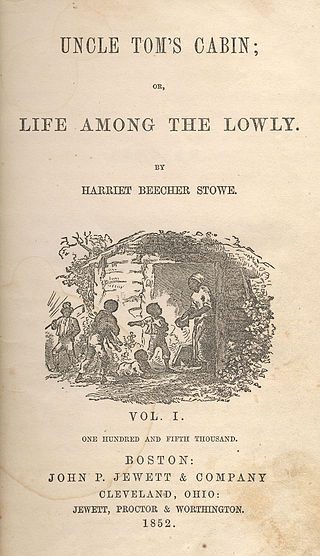

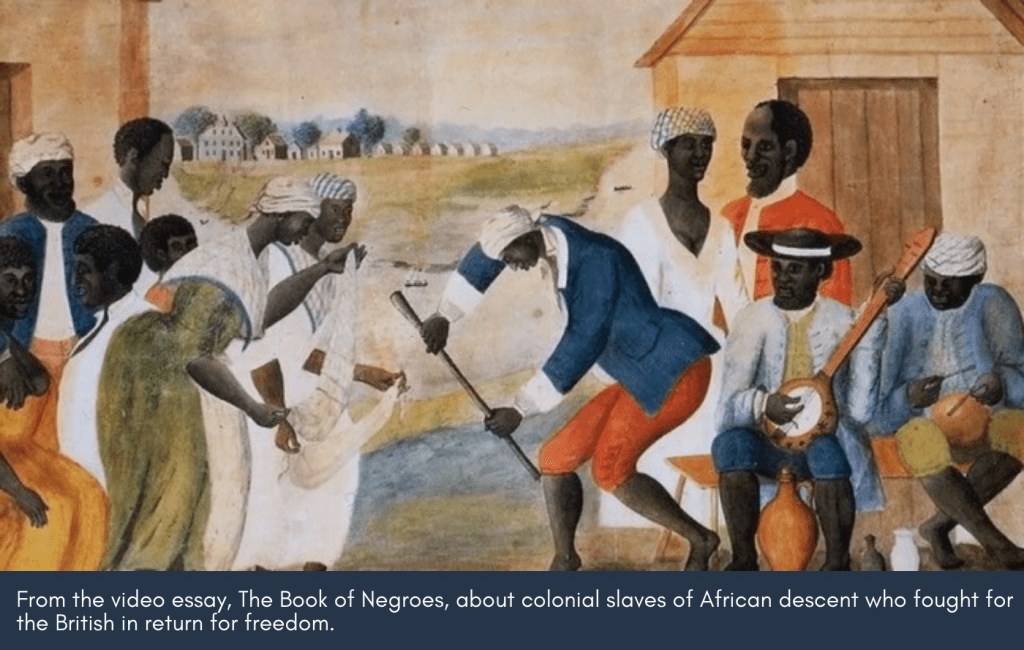

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was far more than just a novel–it was a dramatic literary attack on the immorality of slave holding. Over 300,000 Americans bought a copy in 1852 alone, making it one of the most widely-read abolitionist texts in American history.

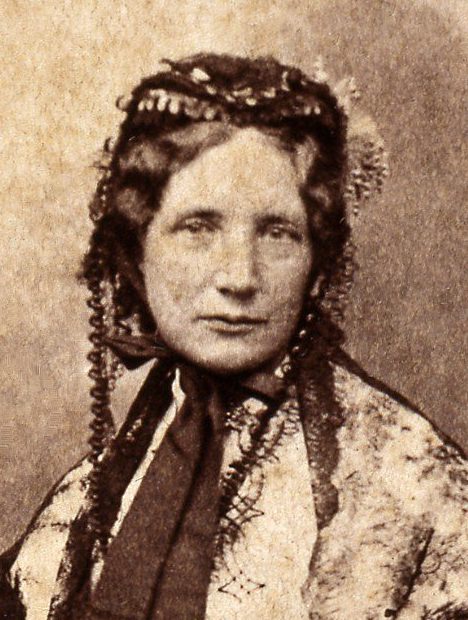

In order to explain the abolitionist message of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Haley Miller decided to assume the dramatic role of Harriet Beecher Stowe and let her tell the tale. Haley talked about the inspiration behind this unique project and the process of performing as one of America’s most famous writers.

Last year in my U.S. History class, I learned about Uncle Tom’s Cabin as a major event in the Abolitionist Movement. It shocked me that Lincoln described its author as “the little lady who wrote the book that started this great war!” I decided to read the novel over the summer to understand its impact on slavery. It truly touched me the same way it touched earlier readers upon its initial release.

I chose the individual performance category because I have enjoyed my past experiences in living history. The book’s author seemed to me the best person to tell its story. As I created my script, I decided to emphasize Stowe’s events that urged her to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the reaction of the public to the bestselling novel of the nineteenth century. My performance is set in the parlor of Stowe’s home on the 40th anniversary of the book’s publishing, as if Stowe were responding to questions from reporters. Many of the statements I incorporated are from her letters. Since Stowe’s actions were motivated by her Christian beliefs, I used many biblical references to explain her thoughts.

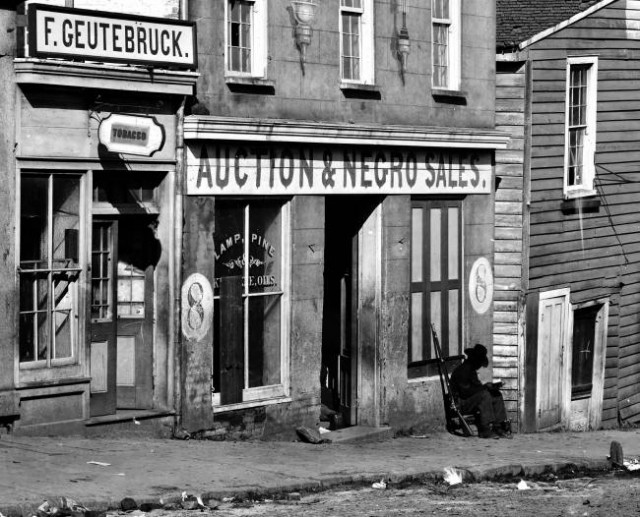

The publishing of Uncle Tom’s Cabin fits the theme, “Rights and Responsibilities in History,” because it equated slaves with whites and spoke out against the Southern system of labor. Stowe explained that, as the Lord’s children, blacks deserve to have united families and to be treated as humans. Stowe believed that God was speaking through her with Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and that it was her Christian responsibility to expose the cruelty of the South. After reading the novel, many felt an obligation to join the Abolitionist Movement to save “Uncle Toms” throughout the United States and to give slaves the right to avoid oppression. It called Christians to put morals over monetary values because, as Galatians 3:28 states, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, neither slave nor free, nor is there male or female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Uncle Tom’s Cabin reaffirmed what our founding fathers wrote, that all men are created equal.

Catch up on Texas History Day:

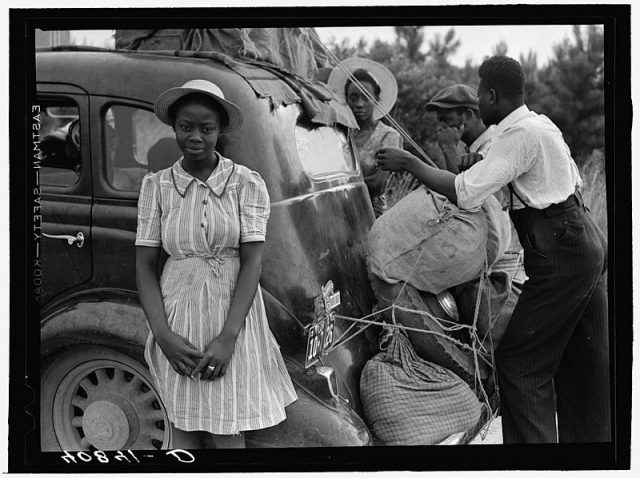

The harsh world of migrant work during the Great Depression

The history behind one of New Orleans’s most iconic neighborhoods

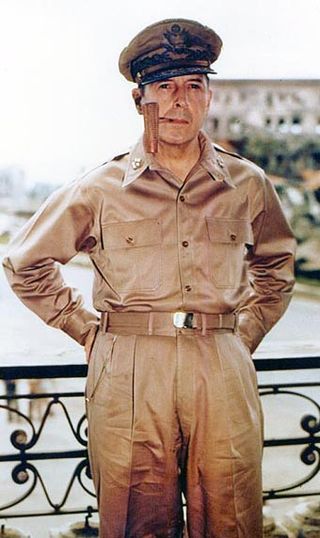

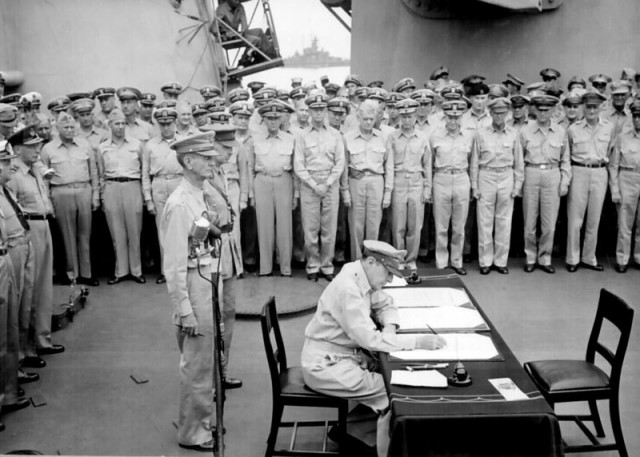

And the story of Douglas MacArthur, right down to his corn cob pipe