By Nakia Parker

After the American Civil War ended in April 1865, white Southerners living in the defeated Confederacy faced an uncertain social, economic, and political future. Many, disappointed in the outcome of the conflict and fearful of vengeful reprisals from the victorious Union government, decided to leave the United States altogether and start afresh in a foreign land. Central and South America, in particular, seemed a safe and welcoming haven for ex-Confederates living in the Gulf South region of Alabama, Texas, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The overwhelming choice of destination for these discontented emigrants was Brazil, where slavery was still legal and the Emperor offered attractive economic incentives, such as inexpensive land ownership and favorable tax laws. These expatriates, possibly numbering into the thousands, became known as “Confederados,” the Portuguese word for “Confederates.” However, not everyone living in the recently vanquished Confederate States of America was keen on the idea of beginning a new life in Brazil. An editorial written on the August 25, 1865 in the Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph meticulously weighs the advantages and disadvantages of the Brazilian emigration movement.

Transcription of the editorial that appeared in the Houston Telegraph

In an attempt to “look at the question fairly,” the editorial highlighted similarities between Texas, the South in general, and Brazil, such as their comparable climates and agricultural production. Yet, the parallels abruptly stop there. The writer of the piece employed common racial stereotypes of the day, claiming that while both Brazil and the U.S. South each had “plenty of free negroes,” people of Afro-Brazilian descent were “of a much lower order of intelligence than ours,” yet enjoyed “social equality.” Even more interesting is the emphasis on the commonalities between Black and White Southerners — their shared religion, language, and “familial” ties — ignoring the devastating, bloody conflict over slavery that just ended a mere few months prior.

Thus, the seedlings of the “Lost Cause” mythology of paternalistic slave owners and happy slaves as a part of their extended family reveals itself in the article’s description of Southern African-Americans. Furthermore, the document vacillates from the practical to the poignant, imploring readers to consider such factors as the financial costs of making an overseas move, the health risks of resettling in an unfamiliar land, the repercussions of moving to a country with a different political and religious infrastructure, along with the emotional and psychic wages of leaving behind beloved friends, family, and an established way of life, no matter how “shaken,” for unsure prospects. The author resolutely came to the conclusion: “No Brazil for us. The “land of the South, imperial land is still for us our home and grave. We hope to go to heaven from it.”

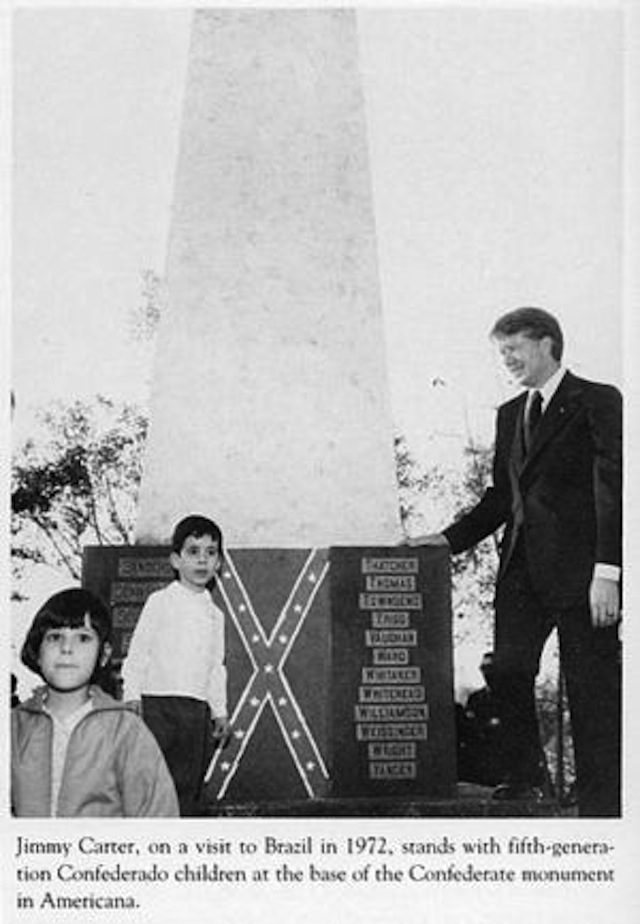

Despite the objections of the unknown writer, many Texans did leave for Brazil. Today, many of their descendants honor their American South/Brazilian lineage with a festival known as the Festa Confederada. This annual celebration combines Brazilian culture, such as dances and music, with traditional “Southern” foods, Confederate uniforms, antebellum dresses, and the waving of Confederate flags. This proud, yet problematic, commemoration highlights the powerful hold that the Civil War exercises not just in the American South, but in the “global South” as well.

More amazing finds at the Briscoe Center:

A Texas Ranger and the Letter of the Law

“The Die is Cast”: Early Texans Face the Comanches

Standard Oil writes a “history” of the old south

Stephen F. Austin visits a New Orleans bookstore

All images via Wikimedia Commons.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.