By Ben Breen

Sanjay Subrahmanyam is a historian of remarkable erudition and imagination. His personal itineraries over the years—from the New Delhi School of Economics to the École des Hautes Études in Paris, and from Oxford to UCLA, where he currently holds an endowed chair in history—mirror those of the early modern travellers who frequently take center stage in his historical work. The book reviewed here (the second volume of Explorations in Connected History, which includes a companion volume called Mughals and Franks) is a collection of eight incisive essays penned by Subrahmanyam between 1993 and 2003.

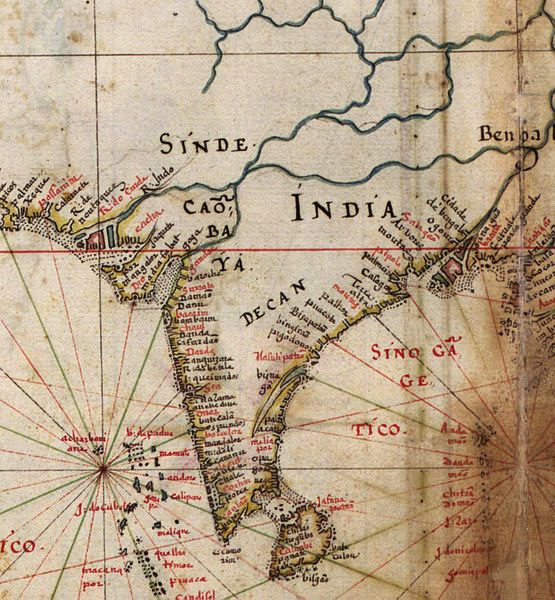

As Subrahmanyam notes in his introduction, these essays “had a rather complex evolution.” The first chapter, a previously unpublished reflection on the scope of “Indian history” as a field of study, began life as a lecture at the University of Oxford. Chapter two, on Asian perspectives on the Portuguese colonies in the Indian Ocean, is a translation from an edited volume published in Portuguese, while the third chapter previously appeared in an edited collection on the Bay of Bengal. Other chapters originally appeared in a range of scholarly journals. Although these chapters range extremely widely, they are bound together by Subrahmanyam’s methodological concern with what he calls “connected histories.”

The notion of “connected histories” is, for Subrahmanyam, a necessary corrective to at least three distinct historiographic trends. First, it seeks to move away from what Subrahmanyam regards as an overly simplistic, isolated, and “mechanistic” framework for writing global histories that has prevailed in the past: comparative history. Second, Subrahmanyam’s connected history methodology seeks to expand the geographic and thematic scope of what we mean by “the early modern period.” The societies that existed in the Old and New World prior to European imperial hegemony, he suggests, were participants in a nascent modernity that was taking place organically and chaotically on a global level, rather than being engineered by European states. And finally, Subrahmanyam marshals the notion of connected histories to challenge what he considers to be a submerged form of “exoticism” at work in post-colonial studies. Subrahmanyam, never one to shy away from a scholarly confrontation, takes special aim at the Subaltern School, which he critiques for “see[ing] the Indian role as one of largely reacting and adapting to European initiatives.”

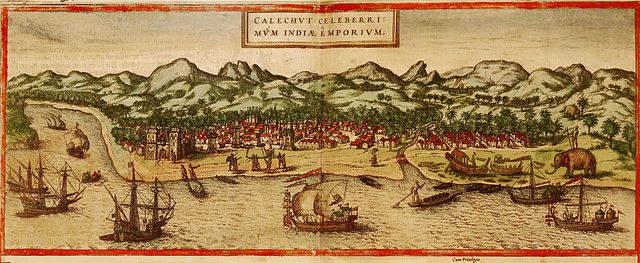

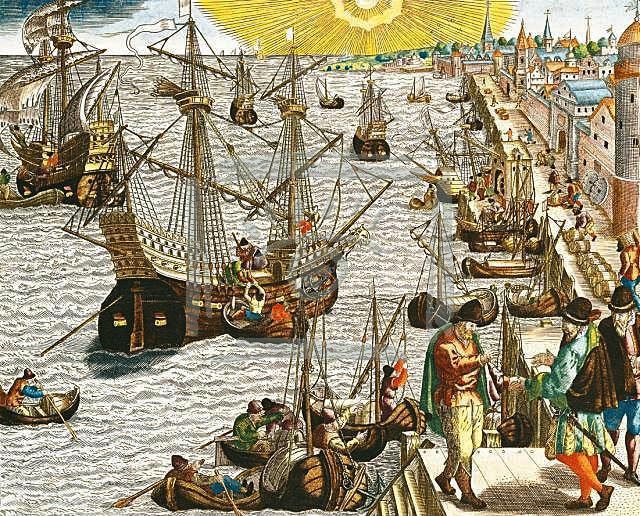

What, then, does a connected history methodology offer in place of comparative history, early modern European history, or post-colonial studies? Subrahmanyam is that rare historical writer who is equally skilled at intervening in big-picture historiographic debates and digging deeply in difficult archives and specialist bodies of knowledge. The work on display here amply demonstrates the promise of his methodology. Subramanyam engages closely with Portuguese chronicles of Indian conquest and the rather myopic Lusophone historiography that has built up around them, showing that a careful attention to alternative narratives—like texts written in Malay, Arabic, and Farsi—can challenge many of our prevailing assumptions about European colonialism. Crucially, Subramyam differentiates between the various imperial powers in the Indian Ocean—not only the Portuguese, Dutch, and British, but also non-European polities. This sets his work apart from other big-picture studies of what was once called “the Age of Expansion” (like Andre Gunder Frank’s ReOrient or Janet Abu-Lughod’s Before European Hegemony), which suffer from a tendency to sort the region’s actors into overly binary “European” and “non-European” camps.

Although the essays in this book focus on south Asia, Subrahmanyam makes clear that the problems of Indian historiography—what he calls “an extravagant nationalism and crude ‘presentism’”—are not unique. From France to Java, historians have tended to reify contemporary distinctions between regions as if they were immutable historical facts. But if part of Subrahmanyam’s aim is to “complicate” (that favorite verb of historians) our understanding of nation and place in the early modern world, he also seeks to clarify. Subramanyam’s connected history approach, which shares a family resemblance to Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra’s “entangled empires” and Joseph Fletcher’s “integrative history,” is not a totalizing effort to explain all of world history à la Toynbee. But it is ambitious in both its geographic and linguistic scope. Marshaling his remarkably polyglot erudition, Subrahmanyam argues that the early modern world must be understood as a porous network of regions and local communities rather than as a patchwork of well-defined states. Although this framework demolishes facile comparisons between, say, “French” and “Indian” mentalities or cultural practices, it also allows us to think in a more theoretically well-defined way about the connections between the societies and regions of the early modern world.

The advantages of such an approach are apparent in Chapter Five of this volume, which advances the startlingly original thesis that a “millenarian conjuncture… operated over a good part of the Old World in the sixteenth century.” In other words, a set of apocalyptic beliefs and concerns were shared between both Portuguese mariners and the South Asian merchants and courtiers with whom they interacted. Fears about portents, omens and signs, no less than currencies and gems, flowed between Europe and the Indian Ocean in this period. Although scholars of Reformation-era Christianity have written extensively on the apocalyptic currents of this era, Subrahmanyam’s mastery of Persian, Turkish, and South Asian sources allows him to connect this historiography to what he calls the “messianic pretensions” of the Persian ruler Isma’il, to various strands of Sufi mysticism, and to the medieval Alexander legends. It is a bravura display of learning that also sets up a bold new framework for thinking about religion as a factor in early modern globalization.

One potential objection to Subramanyam’s connected histories framework arises from his own erudition. The promise of such an approach is obvious in his own work. But this work depends upon a mastery of a dozen languages and the kind of deep historiographic knowledge that takes decades to amass. Who else, besides Sanjay Subrahmanyam, is capable of working in the framework he advocates? History needs more historians who are able to cross national and linguistic boundaries, yet the North American and British academies continue to require historians to specialize on area studies or nationalist historiography. Scholars with the polymathic knowledge on display here are rare, and producing more of them may well require a new approach to how we train young historians.

Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Explorations in Connected History: From the Tagus to the Ganges, (Oxford University Press, 2004)

You may also like:

Bradley Dixon, Facing North From Inca Country: Entanglement, Hybridity, and Rewriting Atlantic History

Christopher Heaney reviews Poetics of Piracy: Emulating Spain in English Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013)

Jorge Esguerra-Cañizares discusses his book Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-170 (Stanford University Press, 2006) on Not Even Past.

Christopher Rose recommends The Ottoman Age of Exploration (University of Oxford Press, 2011) by Giancarlo Casale

Renata Keller discusses Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 (Yale University Press, 2007) by J.H. Elliott

Christina Marie Villarreal recommends Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (University of Chicago Press, 2012) by Daniela Bleichmar

All images via Wikimedia Commons

According to Vladimir Putin, the new textbook must “be based on a single concept, drawing on the same logic of continuous Russian history, on interconnection between all its stages, and respect for all its milestones.” He also noted that the textbook must also be free of any “internal contradictions,” and it should not allow “different interpretations.”

According to Vladimir Putin, the new textbook must “be based on a single concept, drawing on the same logic of continuous Russian history, on interconnection between all its stages, and respect for all its milestones.” He also noted that the textbook must also be free of any “internal contradictions,” and it should not allow “different interpretations.” the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-Aggression Pact, as well as the beginning of the Great Patriotic War) and, finally, the post-Soviet phase (where assessments may be grounded in mass media reports and op-ed articles with varying degrees of bias).

the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-Aggression Pact, as well as the beginning of the Great Patriotic War) and, finally, the post-Soviet phase (where assessments may be grounded in mass media reports and op-ed articles with varying degrees of bias).