Institute for Historical Studies – Monday February 21, 2022

In coordination with Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives, a conference presented by LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections, February 24–25, 2022.

Notes from the Director

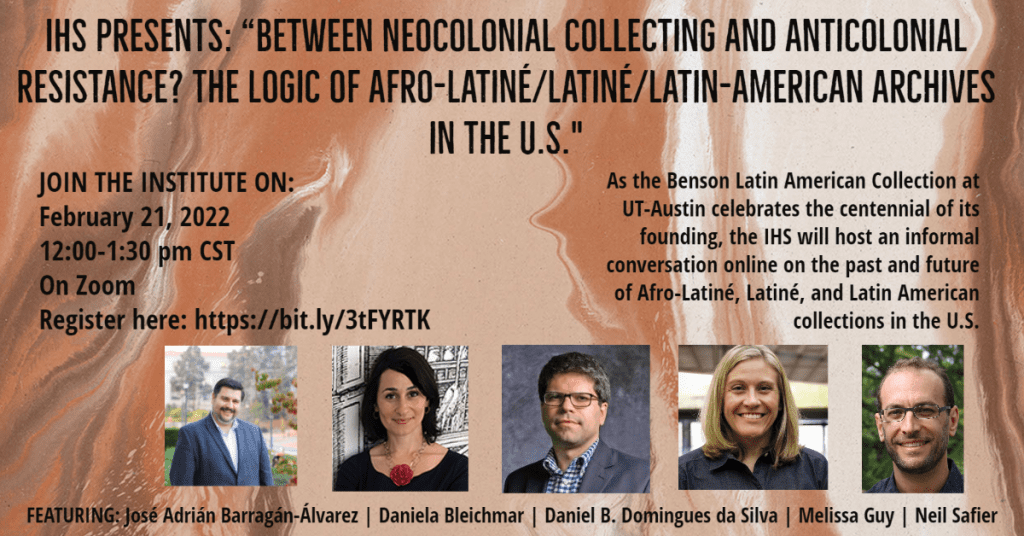

As the Benson Latin American Collection at The University of Texas at Austin celebrates the centennial of its founding, the Institute for Historical Studies will host an informal conversation online on the past and future of Afro-Latiné, Latiné, and Latin American collections in the United States.

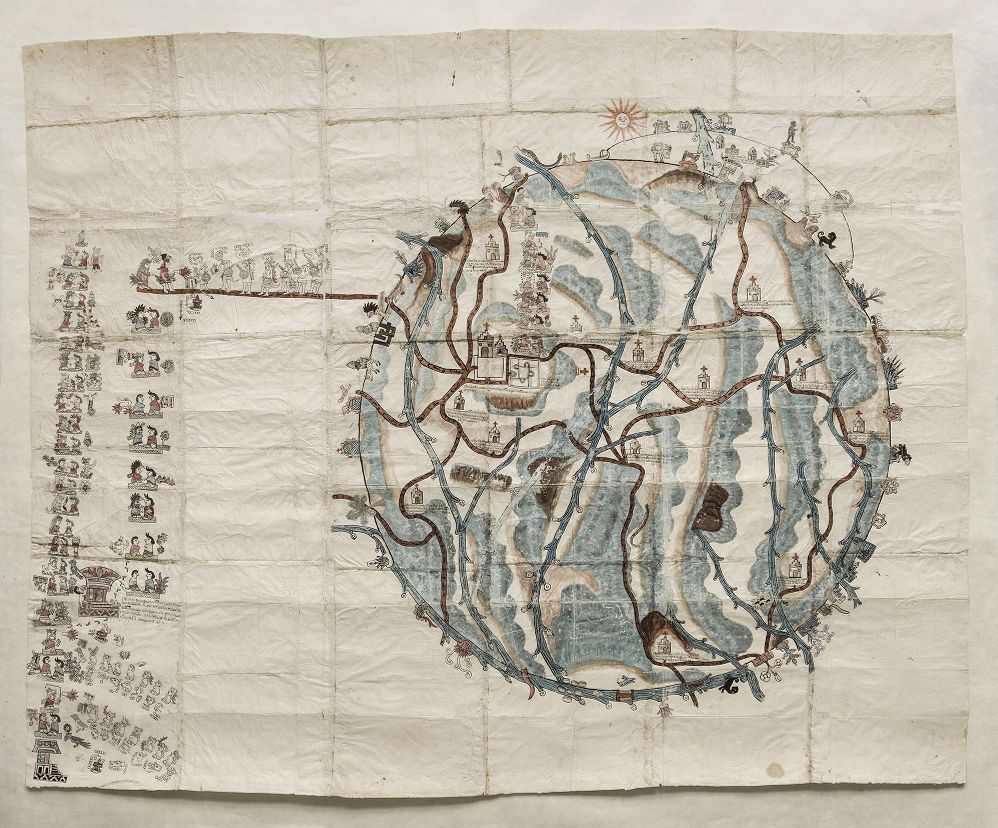

With the acquisition of Genaro Garcia’s massive library on post-revolutionary Mexico in 1921, UT assigned a librarian to organize the collection. In 1934, a specialized library for Latin American materials emerged out of Garcia’s core collection. Only three years later the new library acquired the papers of Joaquin Garcia Icazbalceta, including some of the Indigenous maps prompted by the Spanish crown geographical queries of 1576, known today as Relaciones Geográficas. These images are today a synecdoche for the Benson Library itself. In the 1960s, the Chicano mobilization on campus forced the administration to collect materials on the Latiné experience. While no specialized Chicano library emerged out of the turmoil, the Benson was charged with assembling Latiné collections. The Benson has continued to collect both Latin Americana and Latiné materials.

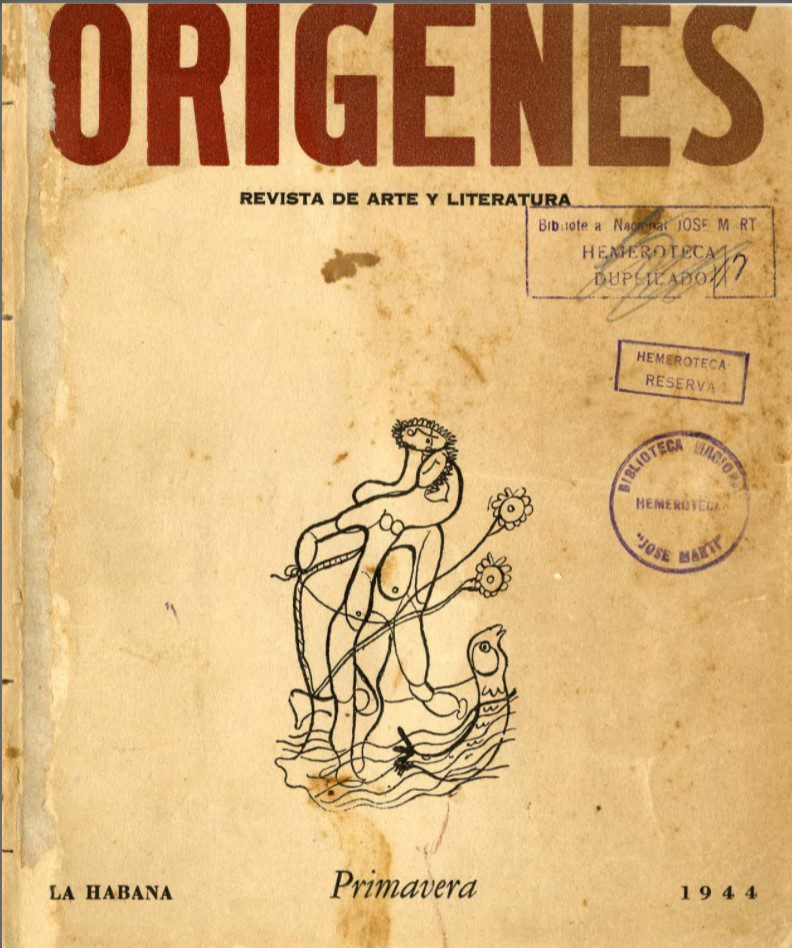

The history of the Benson is a window into several transnational, national, and local processes that are worth exploring. The 1910s and 1920s rise of Hispanism and borderland history among White academics like Eugene Herbert Bolton, the 1920s and 30s expatriation of Mexican collections, the rise of Pan Americanism in the 1940s and the Cold War in the 1960s, and the Chicano student mobilization of the Civil Right Era are all contributing factors to understanding the origins of the UT collections. These same factors help explain many other collections in the U.S., including the Bancroft, Tulane, the Huntington, and the Hispanic Society, among many others.

The purpose of our conversation would be to explore the nature of these various historical developments not only to shed light on the past but to address the future of Latiné and Latin American collections in the U.S. and Latin America.

The end of the Cold War did not put an end to Latin American collecting. The opposite happened. As large waves of migration from Central America and Mexico continued across the border, the U.S. itself became a “Hispanic” society, not just the Southwest. The rapid growth of dual immersion education in Spanish in white middle class neighborhoods is a testament to this larger cultural transformation. More recently, BlackLivesMatter has also made the Afro-Latiné experience more visible after centuries of archival neglect.

How to correct this racist bias that has excluded Afro-Latiné from collections? How to create Afro-Latiné and Afro-Latin-American collections? Have the new politics of Latiné and Latin American identities outgrown the neocolonial and anticolonial forces that first created these collections? Should we continue to decontextualize colonial Indigenous “paintings” as “codices” when they were part of colonial paperwork, documenting various forms of mundane, local, community politics? Should neocolonial Hispanism, the Black Legend, and anticolonial identity politics continue to organize our collecting regimes? How to remember Latin America as the cradle of 19th century revolutionary global republicanism and democracy? Are the processes that have caused Chile to develop the most advanced anti-earthquake engineering in the world also worth collecting? Should we emphasize only archiving the memory of colonialism, poverty, and repression? How to collect a history of Latiné businesses and wealth? How are common transborder experiences changing the priorities of collecting? Should we keep Latiné and Latin American materials separate anymore? What else is worth collecting in the U.S. about Latiné and Latin American societies?

Featured Panelists:

José Adrián Barragán-Álvarez

Curator of Latin Americana

The Bancroft Library

University of California, Berkeley

Daniela Bleichmar

Founding Director, Levan Institute for the Humanities

Director, USC Society of Fellows in the Humanities

University of Southern California

Daniel B. Domingues da Silva

Co-Curator, Slave Voyages digital archive

Associate Professor of History

Rice University

Melissa Guy

Nettie Lee Benson Librarian and Director, Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection

LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections

The University of Texas at Austin

Neil Safier

Former Beatrice and Julio Mario Santo Domingo Director and Librarian, The John Carter Brown Library (2013-2021), and

Associate Professor, Department of History

Brown University

Sponsored by: Institute for Historical Studies in the Department of History; and LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.