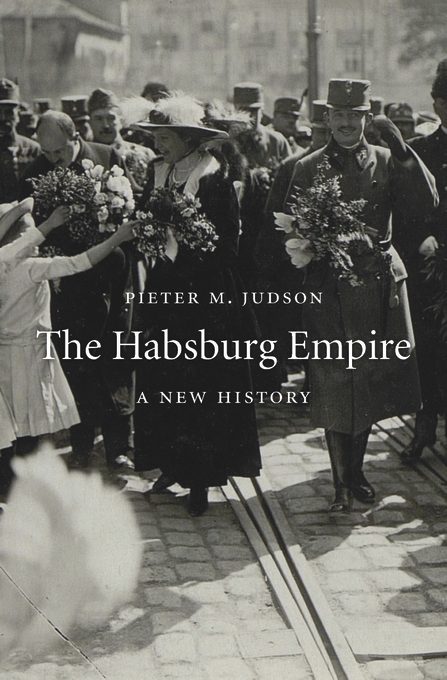

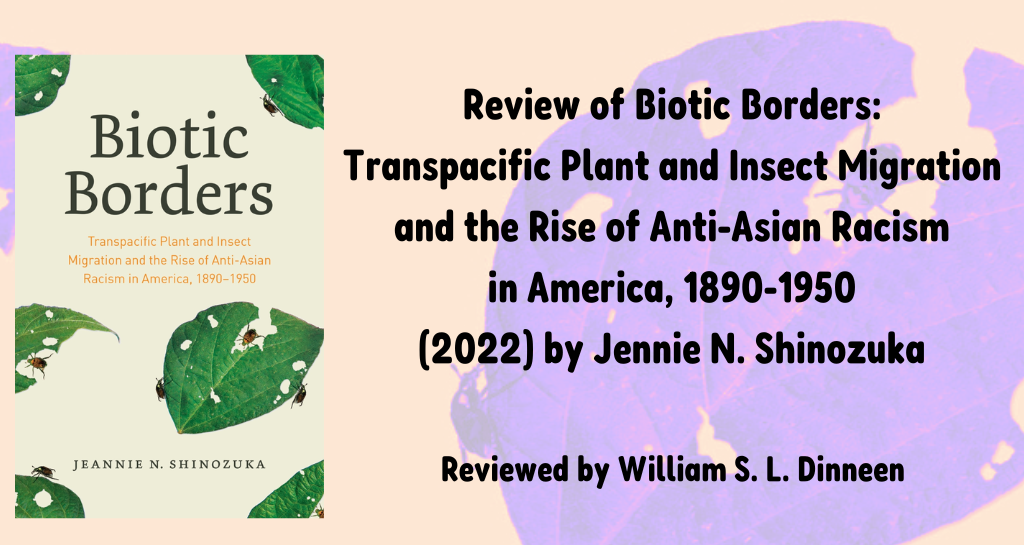

Jeannie Shinozuka’s new book, Biotic Borders, is not only a “history of bugs and other bothers,” [209] but also a demonstration of how ecological actors played a fundamental role in shaping sociopolitical responses to Japanese immigration to the US from 1890-1950. The book shows how racialized invasive species furthered American nationalism in the name of biological security. The othering of invasive species along racial lines and legitimate alarm over environmental destruction contributed to the consolidation of American biotic borders. This review of Biotic Borders highlights how ecological fears were deeply intertwined with racial politics of the era.

Frequently, these invisible eco-invaders—mostly agrarian insect pests—were used by American citizens and government agencies as an excuse to take action against an equally invisible ‘yellow peril’—the increasing number of Asian migrants—through discriminatory agriculture policies, scientific racism, accusations of treachery, medical discrimination, and the consolidation of borders. Indeed, Shinozuka argues that the erection of “‘artificial barriers,’ such as plant quarantines and other regulations ‘redrew’ imaginary lines determined by national boundaries.” [55] In this way, the transpacific ecological borderland enshrined at the end of a romanticized Western American frontier contributed to nationalist notions of a biologically native American utopia, and ultimately, an emergent American empire.

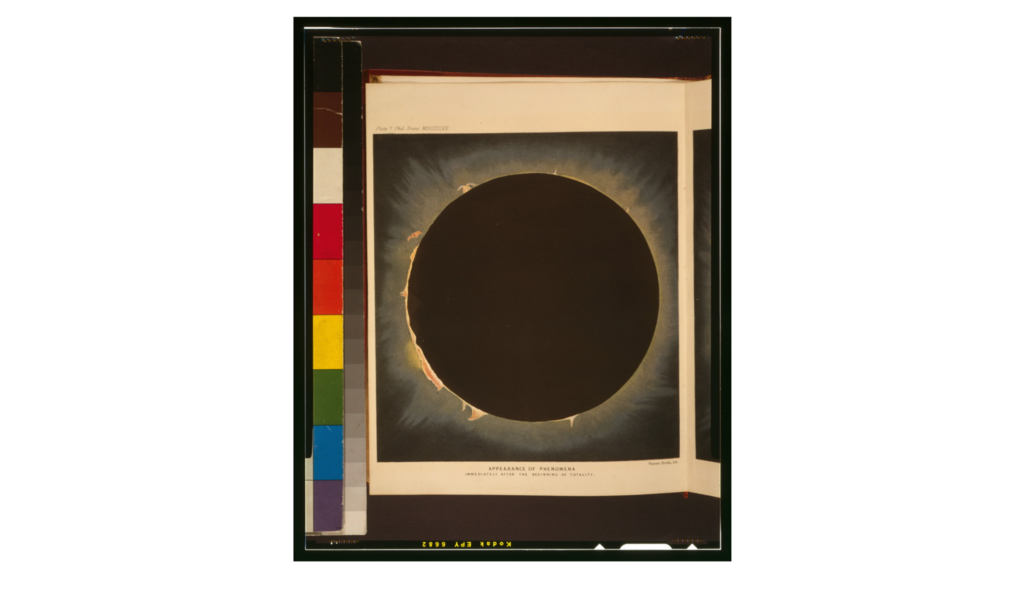

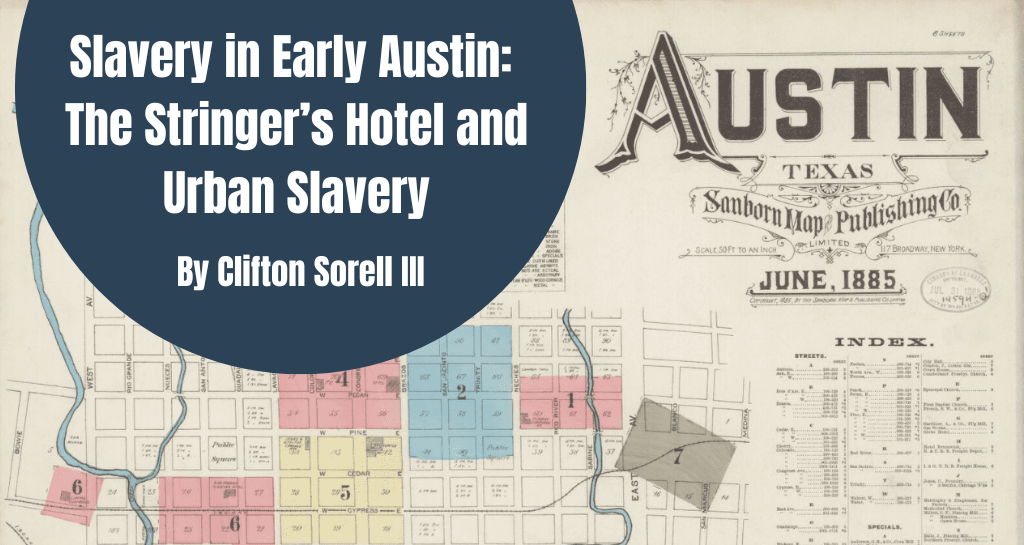

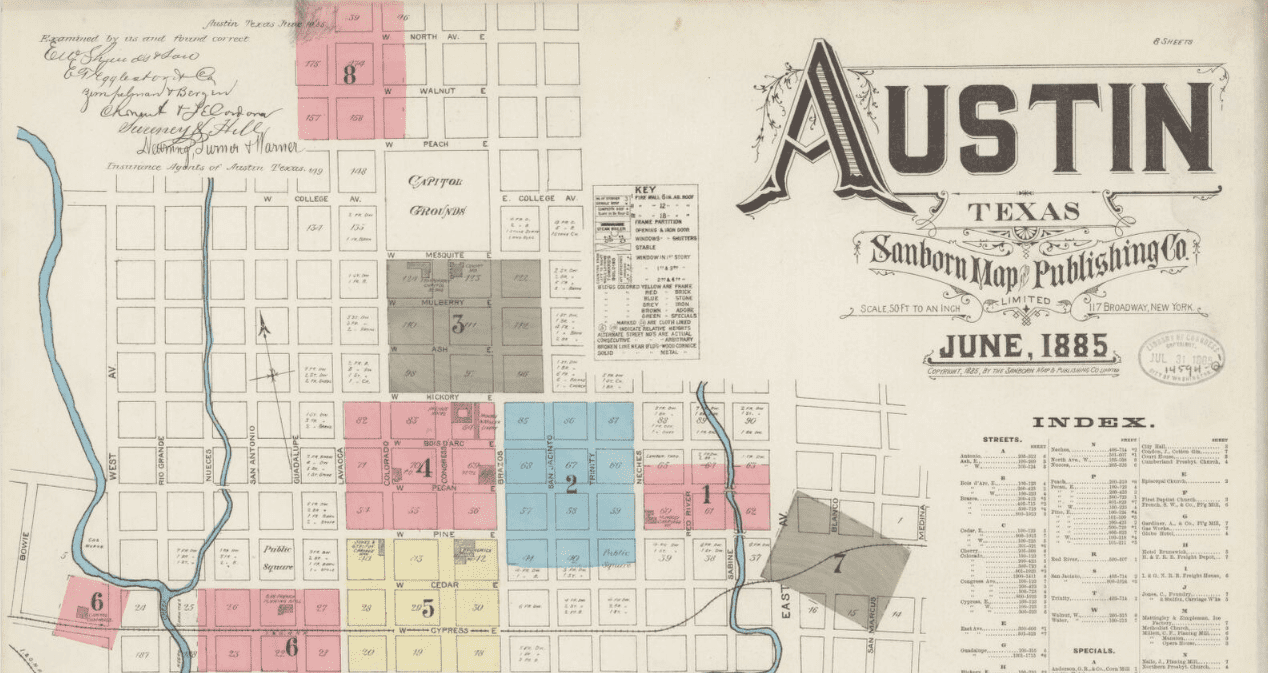

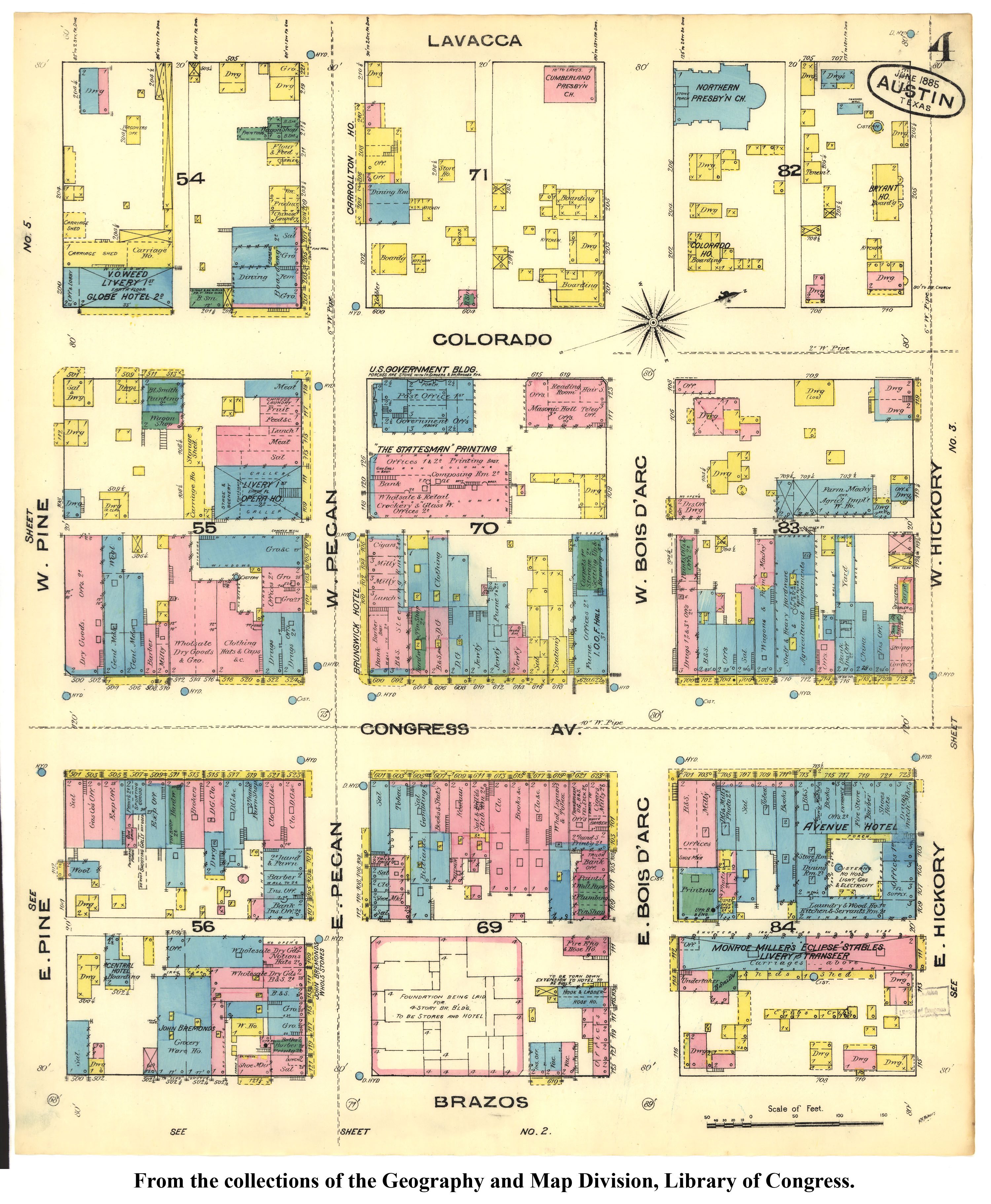

Source: Library of Congress.

Throughout the book, Shinozuka uses ‘immigrant’ in reference to human migrants and the non-human plants and animals that crossed the Pacific during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The human immigrants were the large numbers of Japanese and Japanese-Americans who struggled against pervasive anti-Asian hostility in the United States. The non-human immigrants consisted of the hundreds of Asiatic plant species, and the insects that lived within their fibers, that were shipped and sold in the US to meet a growing demand for Japanese-style gardens and “Asian exotics.” [9] As these two types of ‘immigrant’ became entangled in the American imagination, so too did American hostility towards all foreign species, human or not. However, the word ‘immigrant’ is not the only parallel Shinozuka draws between these two subjects of her book. Biotic Borders is a compelling attempt to connect these two histories, which Shinozuka argues are inextricably bound together.

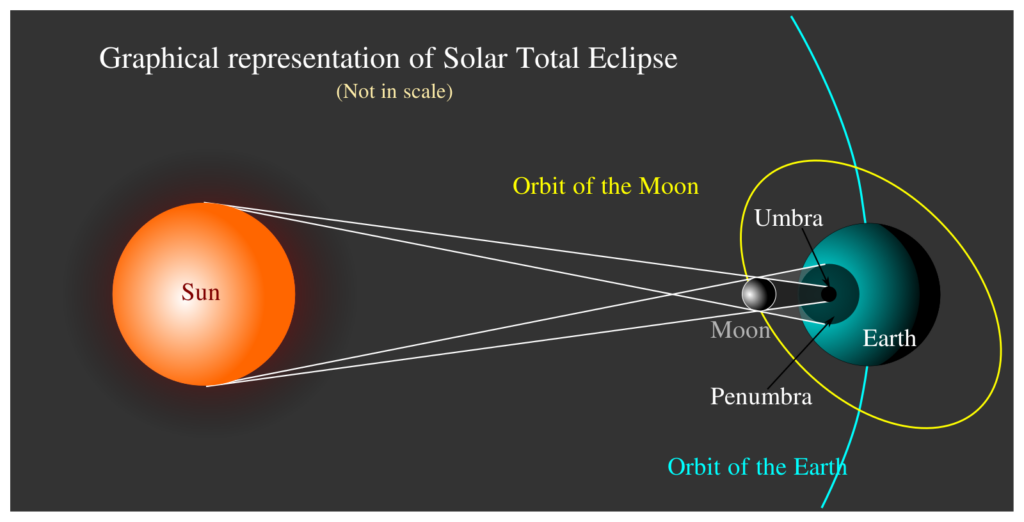

As agriculture in the US became professionalized and monoculture became standardized, the fear of invasive species, imported via increasingly globalized transportation networks, exploded. Entomologists empowered by newly-established government agencies like the Department of Agriculture and the Bureau of Plant Industry sought to uncover the origin of invasive insects. Yet by searching for their non-native origins, these scientists racialized the insects, giving them names such as the Japanese Beetle or the Oriental Scale and facilitating two-way comparisons between humans and insects: the personification of insects and the dehumanization of humans. In turn, these racialized species provoked widespread biological xenophobia, spurred on by the real fear of economic destruction in the agrarian sector, and by a growing desire for environmental border control to protect an illusory vision of American biological nativism. The fear of racialized insects shaped hostility towards similarly racialized human immigrants.

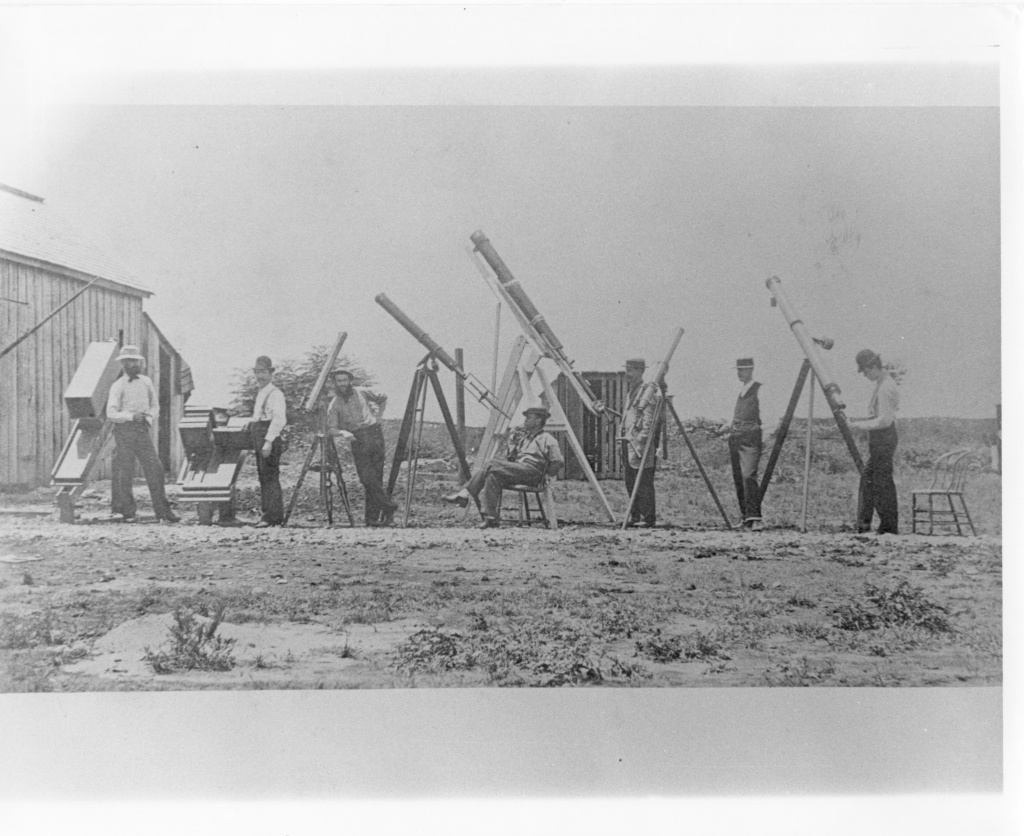

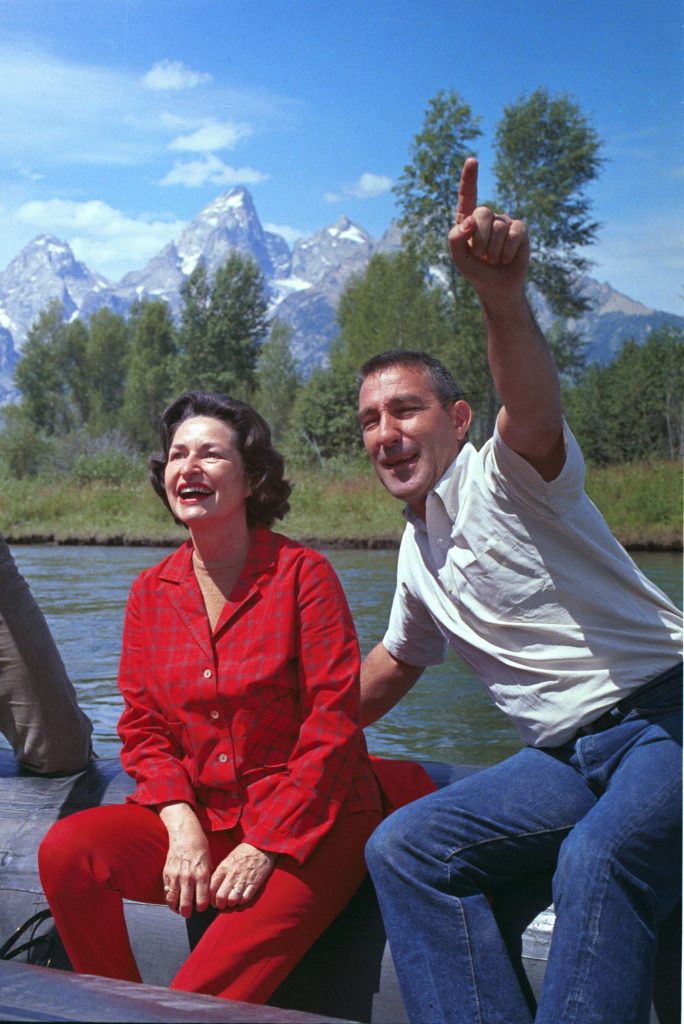

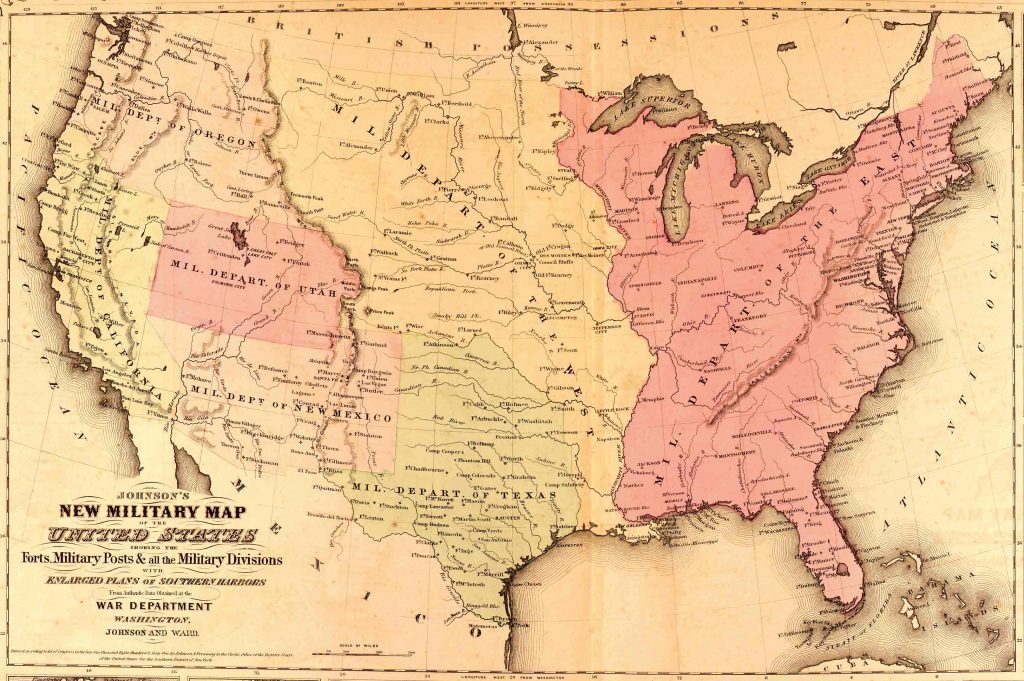

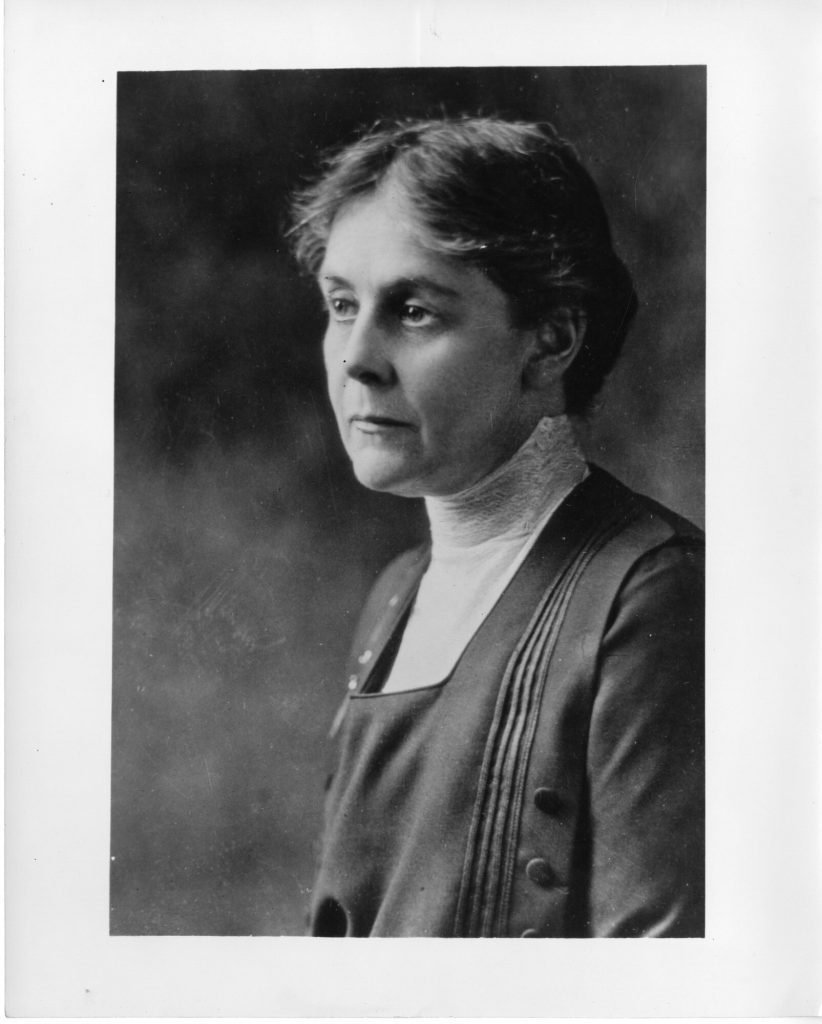

Dr. Wm. A. Taylor, Chief Bureau of Plant Industry, Dept. Agrl, circa 1920.

Source: Library of Congress.

Each of the eight chapters of Biotic Borders is loosely centered around a particular cross-border ecological crisis or invasive species. Chapter 1 focuses on the San José Scale (Quadraspidiotus perniciosus), Chapter 2 on the Chestnut Blight (Cryphonectria parasitica), Chapter 3 on insects at the US-Mexico border, and so on. However, the predominant thread of the book is dedicated to the experience of Japanese immigrants during the growing, racist, anti-immigrant hysteria prevalent at the time. In Chapter 4, Shinozuka explains how Japanese Americans were classified as “unhygienic,” [103] were accused of price fixing and unfair business practices, and were accused of bearing responsibility for hookworm and foodborne illnesses.

Chapter 5 shifts focus to Hawai’i. As a gateway between the US and Asia, Hawai’i became a central focus in securing ecological borders. Shinozuka uses the chapter to demonstrate how scientific authority was deployed as a tool of empire. The remaining chapters cover a growing anti-Japanese paranoia during WWII, including a discussion that joins the incarceration of the Japanese American population and the widespread use of chemical pesticides to combat Japanese Beetle infestations.

Biotic Borders is a thoroughly researched book. Shinozuka uses a variety of sources, including oral histories, to weave together human and non-human narratives. However, occasionally the exact relationship between the human and insect migration is obscured. Whether nativism was a driving force in the creation of ecological borders or whether the creation of ecological borders contributed to growing nativism is unclear in her telling. Similarly, the causal relationship between alarm over Japanese immigration and alarm over plant and insect immigration is sometimes confused. This said, what is clear from Shinozuka’s book is that these processes mirrored each other, and that through one, we gain a better understanding of the other.

By the end of the book, Shinozuka weaves the historical questions of globalization and racism with contemporary challenges. Citing the recent example of COVID-19, she demonstrates how politicians fixated on the Chinese origins of the virus, compared the pandemic to Pearl Harbor and 9/11, and—just like at the end of the nineteenth century—racialized a biotic invader. The book concludes with a direct disagreement with environmental historian Peter Coates who once argued that the brand of “botanical xenophobia” and “eco-racism” [217] presented by Shinozuka had largely dissolved by the late twentieth century. To Shinozuka, as globalization accelerated, science played an increasing role in “the transnational flow of bodies, agricultural products and livestock, and pollution” [219]. She argues that this role is too often obscured when immigration is discussed in a vacuum. Despite its somber content, the book ends with a hopeful note that Biotic Borders could serve as an example for an interdisciplinary, open-ended dialogue about questions of science, racism, nationalism, and ethics.

William Dinneen is a pre-doc research associate at the University of Pennsylvania’s PDRI-DevLab. He graduated with a bachelor’s in history from Emory University where he wrote a thesis about the environmental restoration of the Rocky Flats nuclear facility.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.