By Ted Banks

(This article is reposted from Fourth Part of the World.)

The Progressive-Era white press and their audience had a fascination with Indians judging from the amount of ink that was devoted to musings on their place and progress in society. One component of that fascination, indeed one that was the basis for much speculation on how successfully or not Indians were integrating into white America, was how much “Indianness” could be attributed to Indian blood.

Many observers have noted that notions of blood and “mixing” among whites varied depending on whose blood was being considered. While the “one-drop” rule dictated that a single drop of black blood could overwhelm generations of otherwise Anglo (or Indian) infusion, Indian blood offered no such absolute outcome. At times commenters noted the tenacity of Indian blood, as demonstrated by its ability to preserve Indian physical characteristics across generations. Other times, white observers painted Indian blood as conversely unstable, susceptible to dilution through intermarriage, and seemingly at times, social contact or cultural proximity.

In a 1907 article penned by Frederic J. Haskins titled “Indians Increasing in America,” the author cites several examples of the persistence of “Indian” traits, which he ties to a rough accounting of blood quantum. He notes that the “strength of Indian racial traits is shown by the fact that the 700 persons now in Virginia who can prove their descent from Pocahontas and her English husband, John Rolfe, still have the Indian hair and high cheek bones.” Commenting on a handful of Indian politicians, Haskins introduces “Adam Monroe Byrd, a Representative from Mississippi, [who] is also of Indian blood.” Haskins reports that Byrd “traces his ancestry through a long line of distinguished Cherokee chieftains,” and that “He has the high cheek bones, copper skin and straight hair which indicate the blood of the original American.” Haskins’s article reveals the casual ambivalence with which settlers framed the racial makeup of Indians, and their desire to monitor the relative progress of Indians in America accordingly.

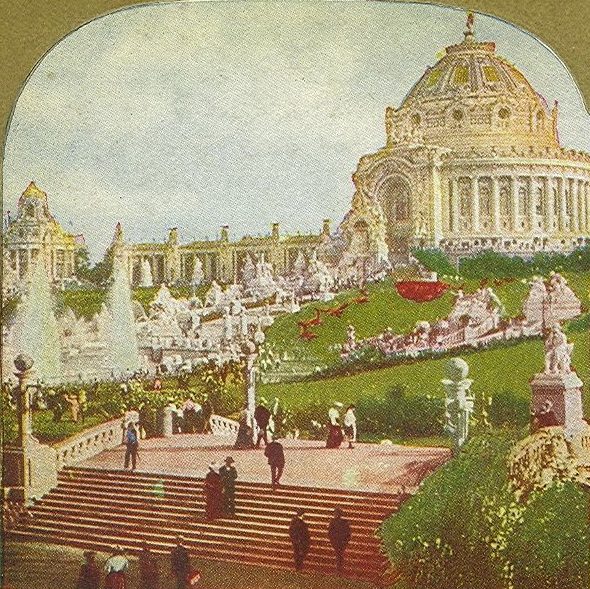

Four years before Haskins’s piece, an article on the upcoming Indian exhibition at the St. Louis World’s Fair played the other side of the ambivalence spectrum while employing much the same rhetoric regarding Indian racial traits. Titled “Pageant of a Dying Race,” the feature dramatically promised the “last live chapter of the red man in American history is to be read by millions of pale faces at the Universal Exposition.” Like Haskins, the author of “Pageant of a Dying Race,” T. R. MacMechen, describes the persistence of Indian racial traits, observing that “(the) blood of Pontiac, of Black Hawk, of Tecumseh and his wily brother, The Prophet, flows in the veins of the descendants who will be at the exposition,” and that “(no) student of American history will view the five physical types of the Ogalalla Sioux without memories of Red Cloud, nor regard the (word unclear) without recalling the crafty face of that Richelieu of Medicine Men, Sitting Bull.” However, MacMechen argues that despite the seeming durability of Indian traits, “the savage is being fast fused by marriage and custom into a dominant race, so that this meeting of warriors becomes the greatest and probably the last opportunity for the world to behold the primitive Indian.” In MacMechen’s account, marriage and custom function as ways to counterbalance, or perhaps mask, the otherwise durable Indian blood.

Festival Hall at World Fair (via Wikipedia)

White supremacy dictated the ways in which whites interacted with racial “others,” but not in such a way that all of these interactions were uniform across groups. That is to say that while intermarriage between blacks and whites was prohibited throughout much of the country on either a de facto or de jure basis, intermarriage between settlers and Indians was, at least at times, encouraged. A 1906 Dallas Morning News piece reported that “Quanah Parker is advocating the intermarriage of whites with the Indians for a better citizenship among the Indians.” The piece noted that “Quanah’s mother was a white woman and several of his daughters have married into white families.” The item quoted Parker as saying “Mix the blood, put white man’s blood in Indians, then in a few years you will have a better class of Indians,” and noted that “(Parker) hopes to live to see the time that his tribe will be on the level with those of pure anglo-saxon blood.” Another DMN article from two years later seems to reveal a gendered wrinkle to such unions, reporting that “(with) the coming of Yuletide Chief Quanah Parker of the Comanche Indians realized one of the greatest ambitions of his life when his young son, Quanah Jr., a Carlisle graduate, was married to Miss Laura Clark, a graduate of the Lawton High School last year,” and that “(this) is the first time in the history of Indians of this section where an Indian has been married to a girl of white blood.”

If persistent racial traits were attributed to Indian blood, but Indians were being “fast fused by marriage and custom” into white society, the result might be some Indians in unexpected places, or at least circumstances. Haskins, in his piece, noted that at the 1904 St. Louis Exposition, “. . . the strong voice at the entrance of the Indian Building calling through a megaphone, . . . (the) barker who thus hailed the passing throng in the merry, jocular fashion of the professional showman was a full-blooded Indian boy, a product of the new dispensation of things, just as Geronimo was of the old.” Of Charles Curtis, a US Senator from Kansas, Haskins observed that “(he) is not of pure Indian heritage, but his mother belonged to the Kaw tribe. . . . He has the hair and color of an Indian, but in politics does not play an Indian game.” A Dallas Morning News correspondent reported in 1906 that Quanah Parker had been elected a delegate to the Republican convention, but that he had declined, stating that he had no interest in politics. The anonymous scribe went on to comment that

Quanah is a half-breed, his mother having been Cynthiana (sic) Parker. Having

white blood in his veins, his conduct is absolutely incomprehensible. For who

ever heard before of a white man, or any kind of a man with white blood in his

veins, who did not want the honors or the salary of office? Still we must remember

that Quanah is King of the Comanches, and that is a pretty good position itself.

The writer’s tone indicates he was speaking somewhat in jest, but the gist of his comment was that Quanah, although possessing “half” white blood by his estimation, was “playing the Indian game” by staying out of politics, and, in doing so, positioned himself a world away from “any kind” of white man.

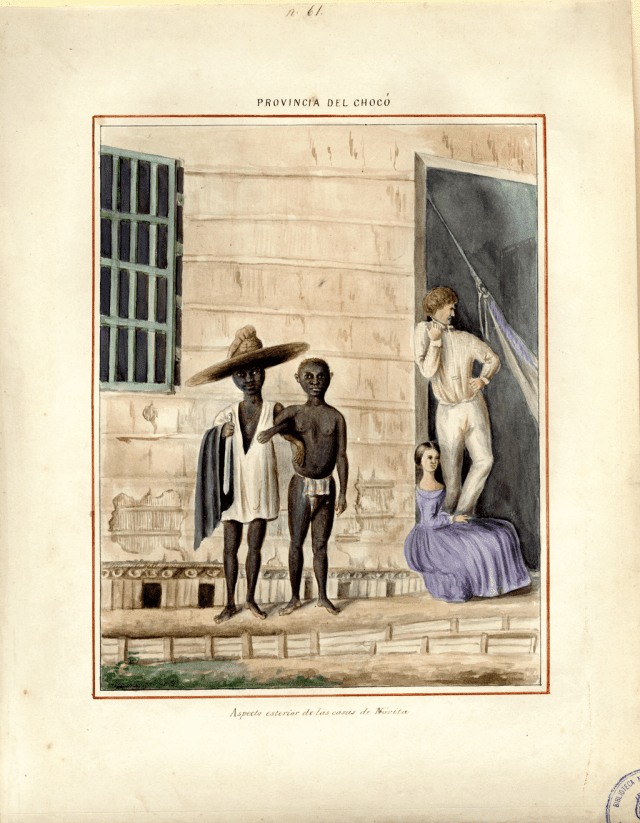

(via Wikimedia)

This is all to say that if one wanted to track the uses of “blood” in white America’s Progressive-Era discourse on Indians, the results would be—excuse the pun—mixed, to say the least. Like their feelings on Indians in general, the habitual deployment of blood as an explanatory concept nonetheless exhibited a remarkable ambivalence; white Americans seemed to think both that “Indian blood” definitely was of immense importance and that it could mean about anything they needed it to. This ambivalence stands out even more starkly when compared to the aforementioned belief in the complete impenetrability of African blood of the same period. A cynical reading might well deduce that white Americans said anything and everything about blood that would help to fortify white supremacy. A devil’s advocate counterpoint might argue that the rise of the eugenics movement indicated that white Americans of the time indeed believed in at least some of what they said. And still another would remind us that both of those could be, and probably were, the case.

You May Also Like:

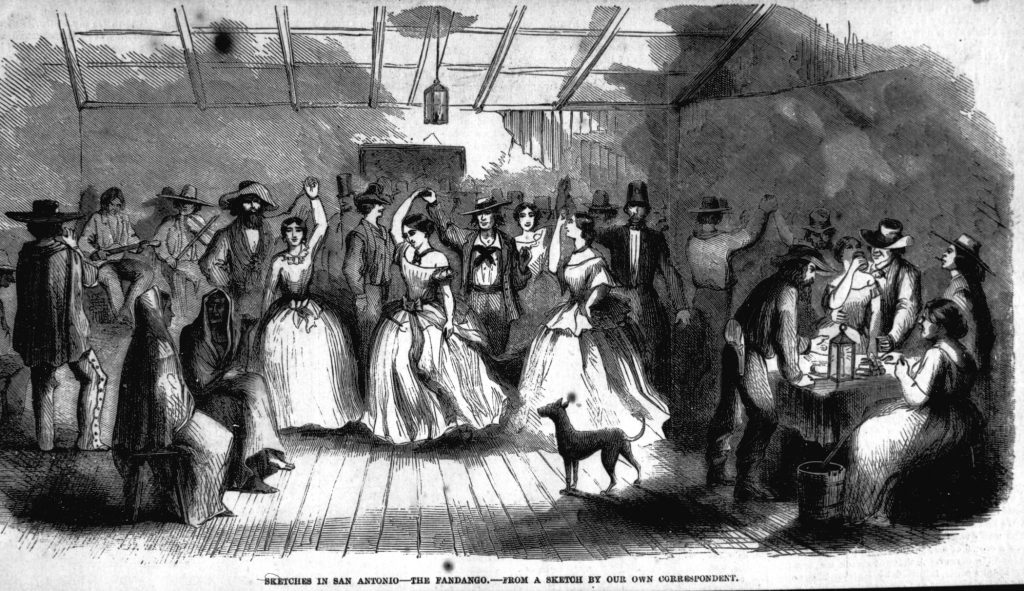

Fandangos, Intemperance, and Debauchery

The Illegal Slave Trade in Texas

Conflict in the Confederacy: William Williston Heartsill’s Diary