The historical value of black life and the casual killing of Eric Garner.

by Daina Ramey Berry and Jennifer L. Morgan

This article first appeared in The American Prospect (December 5, 2014).

In less than a month, our nation will commemorate the 150th anniversary of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery. This should be a time of celebratory reflection, yet Wednesday night, after another grand jury failed to see the value of African-American life, protesters took to the streets chanting, “Black lives matter!”

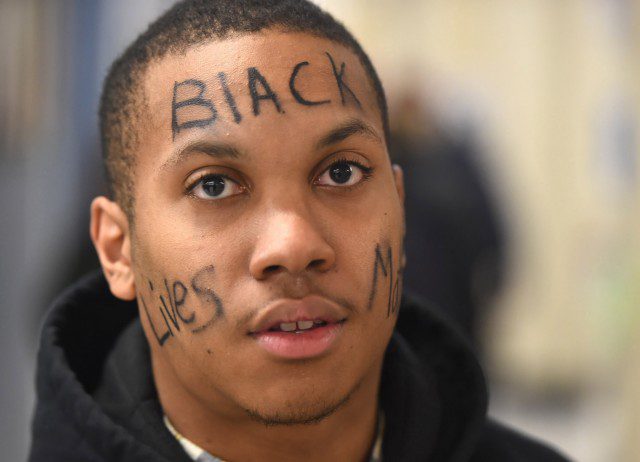

Shippensburg University student Cory Layton, a junior from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, paints his face with the slogan “Black Lives Matter” at the ‘Fight for Human Rights and Social Equity’ rally at Shippensburg University in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, on Thursday, December 4, 2014. (AP Photo/Public Opinion, Ryan Blackwell)

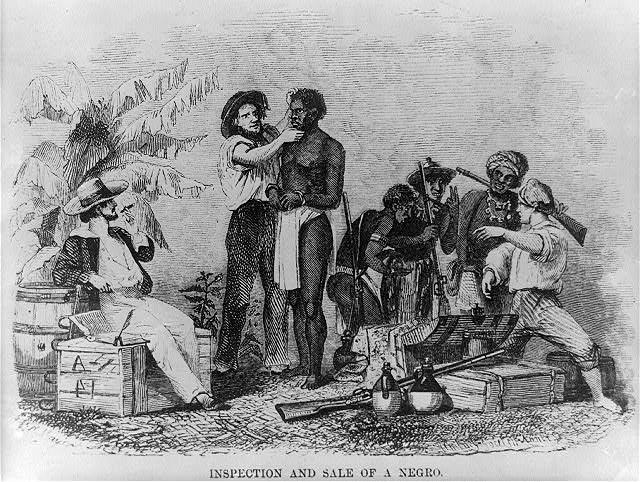

As scholars of slavery writing books on the historical value(s) of black life, we are concerned with the long history of how black people are commodified by the state. Although we are saddened by the unprosecuted deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner and countless others, we are not surprised. We live a nation that has yet to grapple with the history of slavery and its afterlife. In 1669, the Virginia colony enacted legislation that gave white slaveholders the authority to murder their slaves without fear of prosecution. This act, concerning “… the Casual Killing of Slaves,” seems all too familiar today.

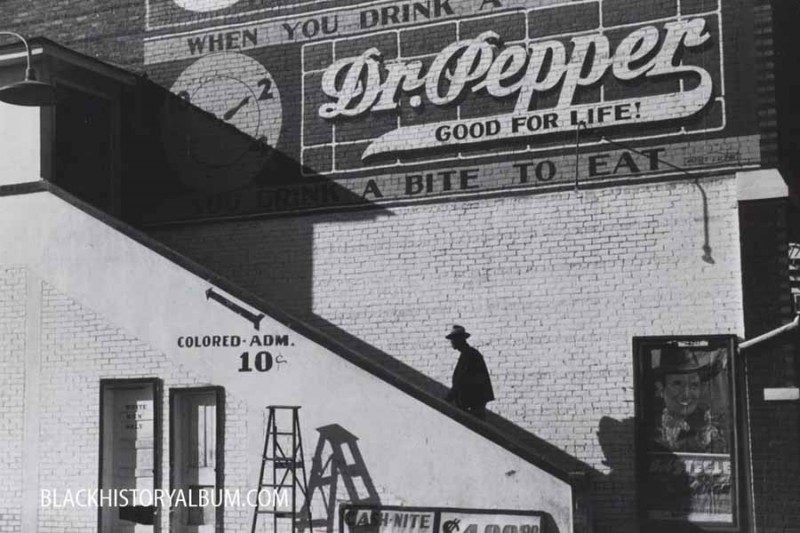

This legislation declared that a grand assembly [jury] could “acquit” those who killed their slaves during a “correction” because a slaveowner could not be guilty of a felony for destroying “his owne property.” Given such laws, the history of commodification before 1865 is clear: The enslaved were chattel—movable and disposable forms of property valued only as long as their labor produced wealth for their owners. A slave in need of “correction” could be destroyed with impunity. Black life existed on a pendulum, either valued or worthless according to the vagaries of the marketplace. With the abolition of slavery, it appeared that black life would no longer be determined by the starkness of a racial marketplace; however, in the aftermath of slavery, the devaluation of black life continues.

The abolition of slavery did not do away with the commodification of black people. Instead, in a nation founded on the idea that black life was only of value when it produced wealth for the elite, free black people became associated with sloth and violence. Slavery meant that black people had no intrinsic human worth, but were only of interest for the monetary value that they could convey. Apparently, freedom could not dislodge the fundamental belief that casual killing could be excused. Free or not, black men and women have remained disposable.

In 1886, in the heart of the Jim Crow South, Hal Geiger, an African-American attorney and prominent leader of the black community from Texas, was shot five times in court. The prosecuting attorney and confirmed shooter, O.D. Cannon, did not like the way Geiger spoke to him. Taking the law into his own hands, Cannon pulled out a pistol and shot Geiger, who died a month later. It took 10 minutes for a jury to acquit Cannon of this “crime.” Twenty years after slavery, the state exonerated the murder of an African American, killed in full view of a judge and jury in a courtroom. Clearly Geiger’s life, and the lives of the black women he was defending, had no value in the eyes of the jury. Black death was deemed the legitimate and justifiable response to a black man who’d transgressed the boundaries of his proper place.

We live at a moment when many black men and women have secured our economic and social standing in this country—a moment at which black men and women occupy positions of prominence, influence and wealth. And yet this spate of murders at the hands of law enforcement clearly tells us that, on a fundamental level, black life does not matter. What does it mean that in 2014 we must warn our children that any one of us can be recast as dangerous monsters, whose pleas for breath, ignored on camera, might awaken the sleeping giant? We must say to ourselves and our children that, for many people, our lives, no longer associated with the accumulation of wealth for others, now do not matter at all.

How could this happen?” This is the question our own children asked us in the wake of the grand jury decisions regarding the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Gardner. This is the question reverberating in our communities. This is the question we ask ourselves. And yet, as scholars of slavery we know the answer. It happened because life that is bought and sold is life that can be reduced to surplus. Life that can be disposed of. Life that can be dismissed.

We are appalled by these deaths. But we are equally appalled by our ability to make sense of them. We live embedded in the afterlife of slavery. We are a nation that has failed to grapple with our past.

When the Virginia House of Commons argued that no one could be charged with committing a felony for a homicide that amounted to the destruction of their own property, it set in motion a racial logic in which we are still entangled. No one will be punished for the taking of black life. Darren Wilson’s actions are understood by the grand jury and many members of his community as unfortunate—but justified. The only valuable thing lost during those four hours as Michael Brown’s body lay uncovered in the street was Officer Darren Wilson’s peace of mind. Million-dollar war chests and speaking engagements will compensate Wilson. Because in the current racial marketplace, the only people compensated for the loss of black lives are those who take them. Black life is only valued when it’s harnessed to white capital.

What we are left with is a perversion of value. A society in which the taking of black life—in public, on camera—is of no consequence. Black men and women appear to be disposable to all but the families and communities who mourn them. We are reduced to the fury and loss and pathos encompassed in our screaming assertion that black lives matter.

Daina Ramey Berry, an associate professor of history and African diaspora studies at the University of Texas at Austin, is a Public Voices Fellow with the Op-Ed Project.