By Fei Guo

China Today was a monthly periodical and the official organ of the American Friends of the Chinese People (AFCP), an organization formed by a group of American Communist Party members and left-leaning intellectuals devoted to introducing the Chinese communist revolutionary movement to Americans. Located in New York, the AFCP also organized public talks on Chinese politics and economics. The journal never became widely popular, with its highest monthly sale of a mere 7,000 copies, yet it remained influential among left-wing intellectuals who shared a concern for events in China.

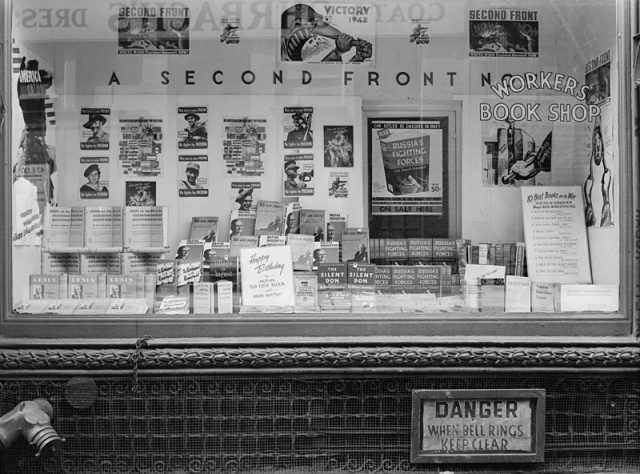

The Communist Party USA’s Workers’ Bookshop, at its headquarters on 13th Street, between University Place and Broadway, New York City. Posters in the window advocate for a U.S. invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe, to open a “second front” in 1942 (via Wikimedia Commons).

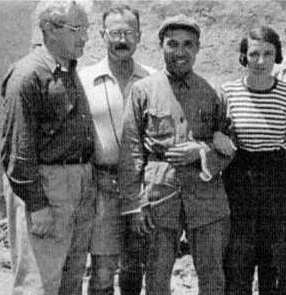

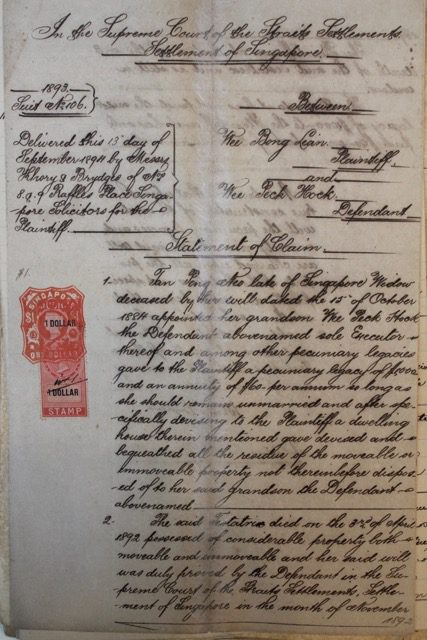

The editors included Philip Jaffe and a secret Communist Party member and graduate student at Columbia University, Chi Ch’ao-ting, using the pseudonym Hansu Chan. Chi joined the Communist Party in America, and together with a few other Chinese students, formed the Chinese Bureau of the Communist Party of USA. With the help of Moscow, Chi was able to receive Chinese Communist Party (CCP) documents, which became an important source for articles in China Today. Chi later returned to China and acted as an undercover agent inside Kuomintang (KMT) government, the main enemy of CCP. Chi eventually became a prominent trade official in Mao’s China in the 1950s. Philip Jaffe, a successful leftist businessman, became well known because of the “Ameraisa” spy case in 1945, in which he and several other Amerasia editors were accused of espionage, after US intelligence agents found classified government documents in their office. The espionage charge was later dropped due to lack of evidence, and they were only punished with fines. Jaffe supported the journal financially since China Today was never an economically profitable enterprise and he gave the journal some credibility. Jaffe became interested in China well before the launch of the journal and, although a leftist, Jaffe never joined the Communist Party, sometimes even criticizing the orthodox Moscow-dominated communist movement.

There were two reasons behind the launch of China Today. First, American Leftists were curious about the Chinese revolutionary movement. Classical Marxism predicted that communist revolutions would sooner or later sweep the world and liberate the whole of humankind. The founding of Soviet Union seemed to confirm the inevitability of the spread of communism globally giving hope to leftists. Many intellectuals believed that China would be the crucial next step in the global enterprise of revolutionary human liberation. A journal dedicated to introducing the Chinese communist revolution would perfectly fit the niche. Second, the journal sought to compete with reactionary news outlets and spell out the Communist perspective on Chinese events for the Anglophone world. China Weekly Review, a prominent pro-KMT government newspaper based in Shanghai was their direct target. Given its limited circulation, it appears China Today only partially fulfilled this object.

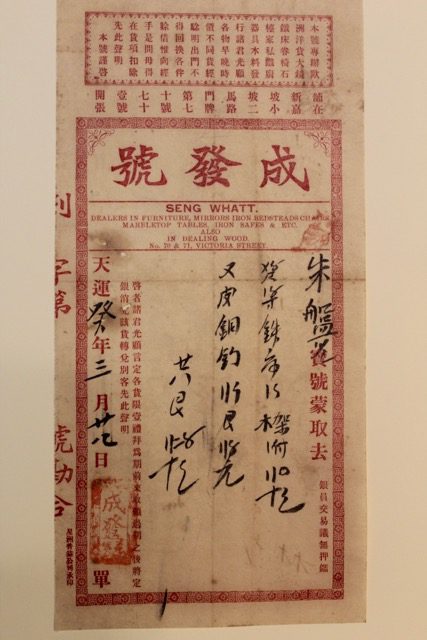

What gave this China Today a special advantage was its ability to procure Chinese communist documents. Because of KMT government censorship, people both inside and outside China had difficulty accessing undistorted political messages of the CCP. China Today offered such an opportunity when publishing original political manifestos or decrees of Soviet China. Chi was the crucial link as he was secretly receiving documents from China.

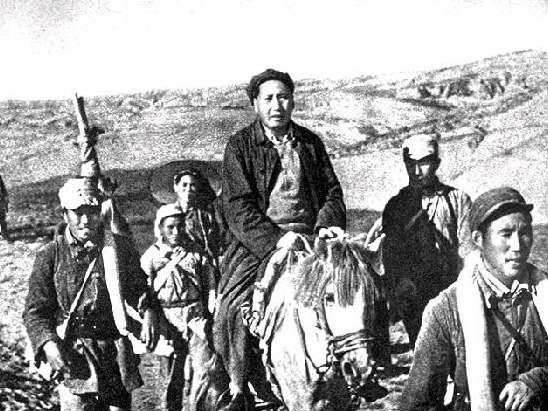

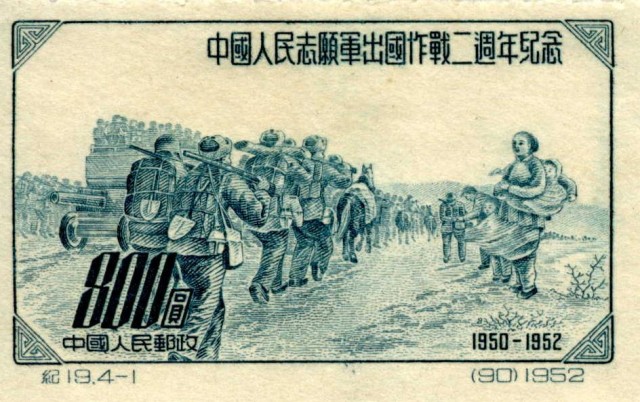

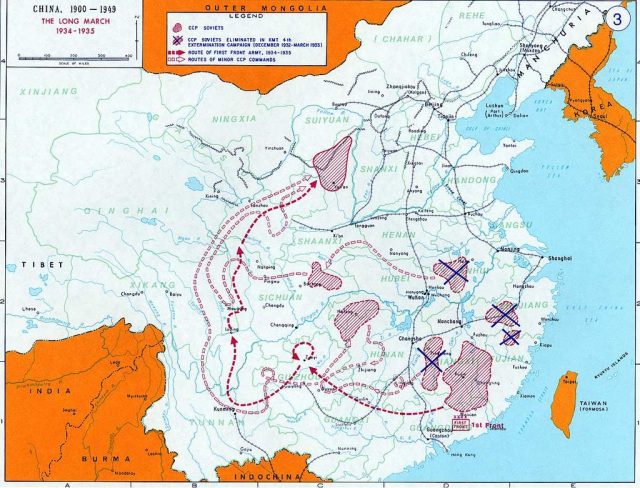

Three reports from China Today give an indication of the character of the journal. The three articles center on Chinese communists’ activities in Szechwan Province during the war between the Nationalist government and the communist insurgency that resulted in the Long March (1934-36) and the ascendancy of Mao Zedong. The first two articles give a detailed account of the origins of Szechwan Soviet Base (1929-35) and the military campaigns conducted by its main force, the Fourth Red Army. The third article surveys the communist military movements towards the latter stages of Long March.

These articles contain important material not available elsewhere and they offer perspectives on the ways Chinese history, in this case the history of the Long March, was framed for an American audience. The heroism and sacrifice of Chinese communists portrayed in these articles are helpful in writing a more nuanced and comprehensive history of Communist China in America. The article on the Fourth Red Army, which occupies a unique position in Chinese revolutionary history, offers both valuable information and a case study in the political shaping of the past. The Fourth Red Army was led by a prominent Chinese communist leader Zhang Guotao (Chang Kuo-tao) who had a huge policy disagreement with Mao Zedong during Long March and even tried to kill Mao in late 1935. Szechwan was the base area controlled by Zhang at that point in time. The Fourth Red Army subsequently was defeated by government troops and suffered huge losses. Zhang lost his power base and eventually defected to KMT. As a result of this internecine fighting, official Communist Party history tends to erase the achievements attained by Zhang in constructing Szechwan Soviet Base. But these China Today articles were published just after the Zhang-Mao split, when the Fourth Red Army was still praised. Given the poor communication during Long March, the editors of China Today were probably still not aware of the inter-party struggle and therefore their account was more accurate and informative than later assessments of Zhang Guotao.

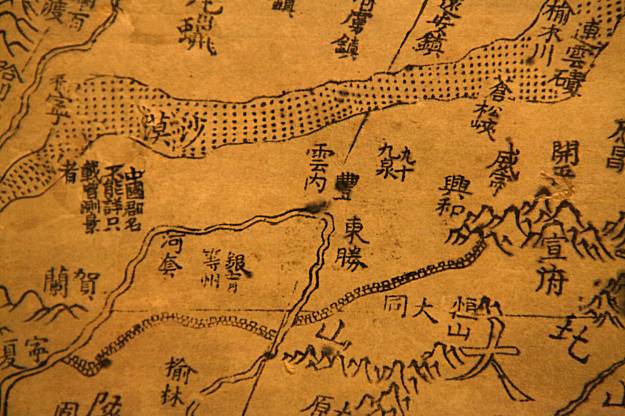

These news reports were about the events occurring during the epic Long March, but the reporters never explicitly mentioned the term Long March or the supposed goal of Long March: to go to North China to fight with Japanese invasion. This is a call to rethink the narrative of Long March. Chinese official history tends to frame Long March in a way that emphasizes the CCP’s superb strategical capabilities and nationalist political agenda. The Long March was considered to be a strategic retreat that has a clear purpose and destination. We can hardly glean any convincing evidence in articles in China Today that support this characterization. The Communist forces acted more opportunistically, striving to fend off government forces and find a favored location for building a new base. This was in fact for a long time a distinct pattern of Chinese communist guerrilla warfare before Long March. Thus, these news reports open a window to scrutinize pro-communist narratives of CCP activities from 1934-36 before a full-fledged account of Long March came into being.

Route of the Long March (via Wikimedia Commons).

The articles in China Today provide useful information regarding both historical facts and narrative building. We still need to be cautious about overstating the achievements of the Fourth Red Army, but in this case, considering interpretations of Long March narratives, the journal’s ideological bias are not an obstacle, but instead a valuable asset.

![]()

Sources:

China Today is part of the Philip J. Jaffe Collection of Leftist Literature in Harry Ransom Center, the University of Texas at Austin.

Stephen Averill, Revolution in the Highlands: China’s Jinggangshan Base Area (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006)

Harvey Klehr and Ronald Radosh, The Amerasia Spy Case: Prelude to McCarthyism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

This essay mainly uses Wide-Giles Romanization System to denote Chinese names and places following its usage in the historical sources being analyzed, except for some well-known Pin-yin names such as Mao Zedong.

![]()

You may also like:

CIA Study: “Consequences to the US of Communist Domination of Mainland Southeast Asia.”

Writing Chinese History.

Peeping Through the Bamboo Curtain: Archives in the People’s Republic of China.

![]()