On February 26-27 2018, The History Department at the University of Texas at Austin was pleased to welcome Dr. Manisha Sinha, Professor and James L. and Shirley A. Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut, as the featured speaker for the Littlefield Lecture Series.

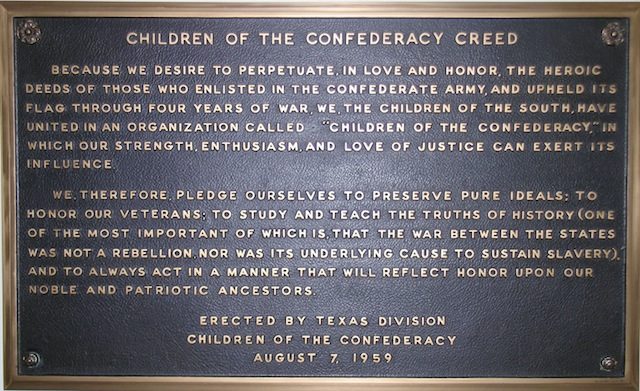

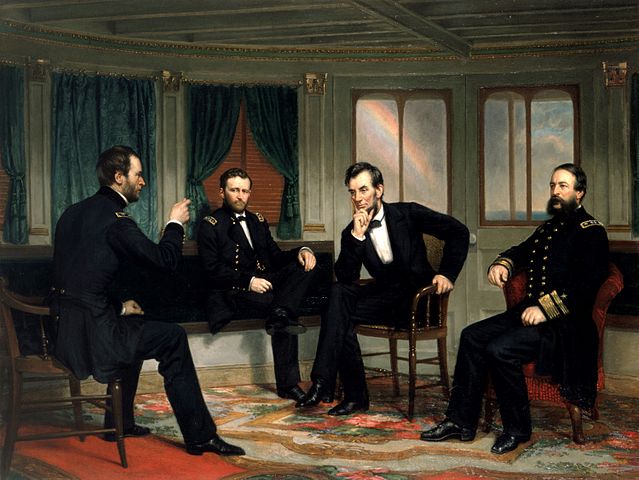

Watch Professor Sinha’s first lecture on Not Even Past, titled “Abolition and the Making of Southern Reaction:”

Dr. Manisha Sinha was born in India and received her Ph.D. from Columbia University where her dissertation was nominated for the Bancroft prize. She was awarded the Chancellor’s Medal, the highest honor bestowed on faculty and received the Distinguished Graduate Mentor Award in Recognition of Outstanding Graduate Teaching and Advising from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, where she taught for over twenty years.

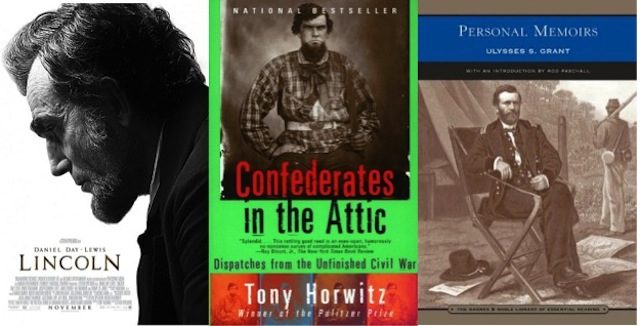

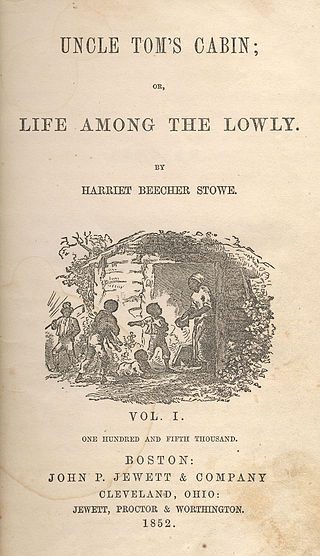

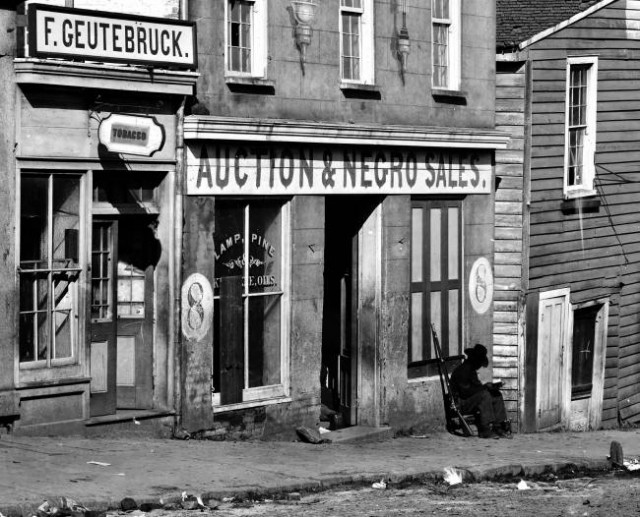

Her recent book The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition, winner of the 2017 Frederick Douglass Prize, is a groundbreaking history of abolition that recovers the largely forgotten role of African Americans in the long march toward emancipation from the American Revolution through the Civil War.

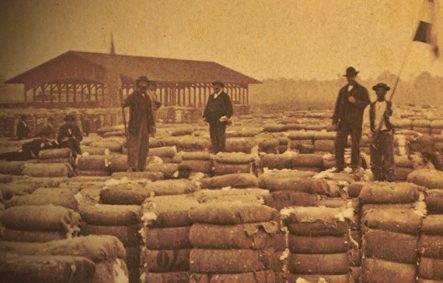

Her first book, The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina, was a Finalist for both the Avery O. Craven Award for Best Book on the Civil War Era, Organization of American Historians, and the George C. Rogers Award for Best Book on South Carolina History. It was named one of the ten best books on slavery in Politico in 2015.

Dr. Sinha’s research interests lie in United States history, especially the transnational histories of slavery and abolition and the history of the Civil War and Reconstruction. She is a member of the Council of Advisors of the Lapidus Center for the Historical Analysis of Transatlantic Slavery at the Schomburg, New York Public Library, co-editor of the “Race and the Atlantic World, 1700-1900,” series of the University of Georgia Press, and is on the editorial board of the Journal of the Civil War Era. She has written for The New York Times, The New York Daily News, Time Magazine, CNN, The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, and The Huffington Post, and been interviewed by The Times of London, The Boston Globe, and Slate.

In 2014, she appeared on Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show. She was an adviser and on-screen expert for the Emmy nominated PBS documentary, The Abolitionists (2013), part of the NEH funded Created Equal film series. In 2017, she was named one of Top Twenty Five Women in Higher Education by the magazine Diverse: Issues in Higher Education. Professor Sinha is currently working on her new book on abolition and the making of Radical Reconstruction.

You may also like:

15 Minute History Episode 105: Slavery and Abolition with Dr. Manisha Sinha

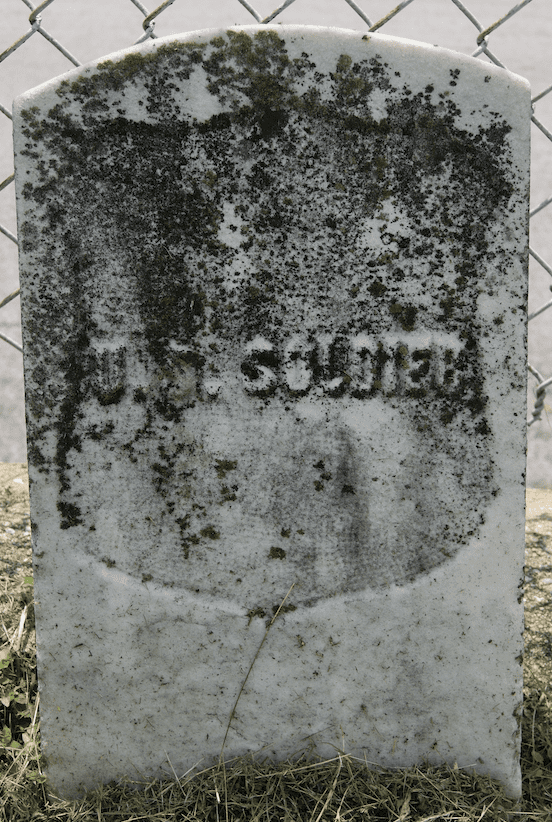

Reconstruction in Austin: The Unknown Soldiers by Nicholas Roland

Work Left Undone: Emancipation was not Abolition by George Forgie

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.