By Rachel Herrmann

In his novel, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, Laurence Sterne describes the character Uncle Toby and his hobby-horse, the military. A hobby-horse, which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as “a favourite pursuit or pastime,” is something you’ve trotted out and ridden nearly to death. At the risk of losing the remainder of my friends, I am here to once again sing the praises of my hobby-horse, Twitter, and explain why you should be on it if you care about history.

Twitter is a website where users can “tweet” their statuses in 140 characters or less. Historians use it to start conversations, to follow people with like interests, and to keep abreast of history-related news and stories (links are automatically shortened so that there’s enough room to fit a comment and a link within the space of one tweet). When people want to talk about a specific topic, they use a hashtag—a phrase preceded by the “#” sign—which then becomes searchable. Basically, it’s a way to have all your history information in one place.

Twitter’s short, snappy platform for allowing people to communicate means that tweets have generated blog posts, conference papers, and articles. News travels fast on Twitter; when that earthquake hit Virginia in August 2011, I had friends in New York who read about it on Twitter before they felt the ground rumble beneath their feet. These possibilities for lightning-fast networking have engendered the rise of a group of historians on Twitter known as #twitterstorians. They’ve been around for over two years now. When you put that hashtag in front of the phrase “twitterstorians,” anything that the #twitterstorians are talking can be searched for on Twitter.

A growing group of professors and graduate students from UT’s history department are on Twitter. Our very own Not Even Past (@NotEvenPast) is on there, tweeting about recent blog posts, book reviews, podcasts, and short history articles. H.W. Brands (@hwbrands) is tweeting the history of the United States in haiku—he’s currently up to President Polk’s election. Jeremi Suri (@JeremiSuri) tweets about foreign policy blog posts, but he also posts links to current events stories and fellowships for students. Ben Breen (@ResObscura) can be counted on for tweets that share interesting, funny, and sometimes disgusting medical remedies in the Early Modern world. Bryan Glass runs the Twitter feed for the British Scholar Society, (@britishscholar), disseminating op-eds on British studies, and listing upcoming talks and lectures. Chris Dietrich (@C_R_W_Dietrich) is on there talking about twentieth-century history and foreign affairs. Brian Jones (@jonesbp) opines on new music, restaurant plugs, and getting writing done. Jessica Luther (@jessicaluther) can be trusted to post about her research on Barbados, with links to interesting pictures from her Tumblr blog. And oh, I’m on there (@Raherrmann), tweeting about research, writing, and food.

In case these glimpses aren’t enough to convince you that there are conversations happening on Twitter that are worth joining in on, I’d like to point out that Twitter is very useful for networking, conference-going, and researching. I’ve met people through Twitter that I’ve then connected with in real life. It’s comforting to arrive in a strange city, and to have a coffee date set up with someone you’ve never met, but have been talking to about history.

Historical organizations, including the American Historical Association (@AHAhistorians), the Society for the History of Authorship, Reading, and Publishing (@SHARPorg), and the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations (@SHAFRConference), have used Twitter at their national conferences. Their tweets gave attendees logistical information before they arrived at the conference, and during the conference, hashtags covered what happened on the ground. Organizers set up a hashtag, and then conference-goers and non-conference-goers alike could follow along with what was happening at panels. Usually, people in attendance live-tweet the papers as people are presenting them—this conversation is called “the backchannel.” At the American Historical Association’s annual conference in Chicago, over 4,500 tweets hit the airwaves.

People who didn’t make it to the conference get to feel like they’re participating. And people who are there don’t have to worry about missing papers when panels are timed to happen simultaneously, because they can read what’s going on at a different panel from a few rooms away. Participating in the backchannel also gives conference-goers the ability to react to a paper as it’s being presented. Panelists can check the backchannel during their presentations so that they can anticipate questions, and they can read up on it afterwards to get almost instant feedback on their papers.

The fact that so many people are using Twitter at conferences has also been useful in getting me to think about those Twitter users when crafting my own conference talks. Gone are the days when I start a paragraph with a five-line long topic sentence. Now, I’m looking at my paper and wondering how listeners are going to condense my words into 140-character sound bites. My arguments come through a bit more forcefully, since I know that people will be multitasking as they listen to me speak, tweet about what I’m saying, and read what other attendees at other panels might be talking about.

The other venue where I’ve found that Twitter is useful is when I’m doing history, and I’m not alone in this respect. Public historians have argued that Twitter has been good practice for creating explanatory displays for museums and exhibits, where captions must be short, but informative. I love using Twitter when I’m off researching. Since I study a topic that demands that I cast a very wide net, I sometimes have days where I’m doing a whole lot of skimming with not much return. Having Twitter open is like having a group of colleagues in the room with you. You can use them to complain to, but you can also field a research question to them, and have five answers in as many minutes. It’s a fun way to share the joys of research; the same holds true for when I’m writing. There’s a group of people there, just waiting to support your recent attack on a bad paragraph, or to agree to write with you and check-in for a progress report every hour.

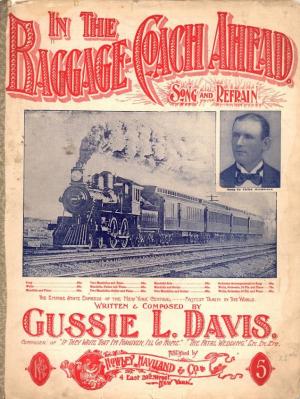

The song was the most popular composition of

The song was the most popular composition of  In 1925, he re-imagined himself as a hillbilly singer and achieved his greatest popularity with

In 1925, he re-imagined himself as a hillbilly singer and achieved his greatest popularity with