October 14th is what most people know as Columbus Day. However, for many Indigenous peoples, the celebration of Christopher Columbus is a reminder of the generations of trauma and settler conquest of Native nations and lands. For that reason, several states, including Alaska, Minnesota, Vermont, and South Dakota (and cities like Austin), have chosen to rename the holiday Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Native activists have been at the forefront of this movement. Here is a twitter thread discussing the global campaigns to reframe the day:

It is difficult to study or teach American history without including Native peoples. That said, many historians limit mention of Indigenous peoples to the period before 1776 or even 1840, but the narrative that the cultures died or were replaced by the United States relegates Native peoples to the past, furthers the colonial project of erasure, and simply does not do enough scholarly diligence. There is a difference between talking about Native peoples and teaching Native histories. “Decolonizing your syllabus” by including one Indigenous, Black, or POC scholar is not sufficient either.

On Indigenous Peoples’ Day, I’d like to suggest some easy additions to your syllabus, playlists, and bookshelf. This is a brief review of some seemingly untraditional academic works by Native authors, scholars, artists, and creators. My reflection on Native literature here includes scholarship in a number of forms that could easily be incorporated into a syllabus or added to your Comprehensive Exam List. This list is a starting point and I’d encourage readers to go further by listening to Native leaders, scholars, and artists.

ART

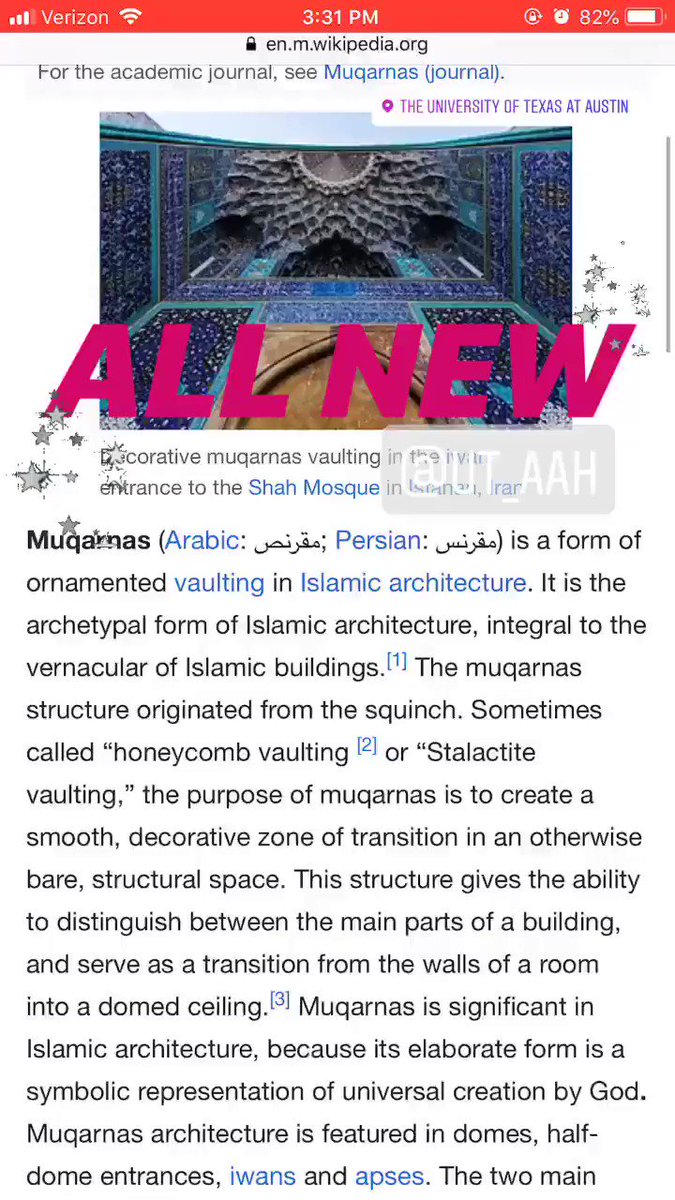

The Blanton Museum of Art recently featured the work of Cherokee and Choctaw artist, Jeffrey Gibson in an exhibit called “Jeffrey Gibson: This Is the Day.” Gibson’s art was recognized by the MacArthur Foundation when he was awarded a 2019 MacArthur Genius grant. The exhibit was celebratory, sincere, and visually stunning. Gibson’s talent was on full display in a wide range of pieces. They included sculptures, textiles, paintings, film, even several boxing bags. Descriptions of each piece were written by Gibson himself. (They are generally written by exhibit curators so to have Gibson’s narration was an honor!)

A room of the exhibition hall was dedicated to the ghost shirt, a garment used by ghost dancers during the ceremony but reinterpreted here by Gibson. Each ghost shirt carries its own symbolism and messaging. Gibson’s use of a wide range of materials, textiles, prints, and textures allows his work to explore ideas of race, sexuality, gender, and religion. Gibson’s perspective bridges cultural practices and modern art forms and visualizes coalitions in the global struggle for Indigenous rights. Gibson wrote, “A garment acts as the mediator between the wearer–myself in this case– and the rest of the world. It can protect me, draw attention to me, celebrate me, allow me to be another version of myself.” The exhibit closed on September 29th, but you can find out more about Gibson’s work on his website.

Frank Waln’s “What Makes The Red Man Red” and “AbOriginal” are must listens. The music video for the former shows imagery and lyrics from Disney’s Peter Pan (1953). Scholars and social commentators have observed the obvious racism in the almost 70-year-old animated film, however, Waln’s work includes both audio clips and an answer to the question “what makes the red man red”?:

You made me red when you killed my people

Made me red when you bled my tribe

Made me red when you killed my people

(Like savages/ Like savages)

In “AbOriginal,” Waln goes home. The lyrics talk of life in his reservation— the pains, protests, and resilience that comes from his tribe.

I got this AB Original soul/ I got this AB Original flow

I got this pain that I can’t shake/ ties to my people I can’t break

Got this history in my blood/ got my tribe that shows me love

So when I rise/ you rise/ come on let’s rise like

Similarly, the music video pays tribute to Waln’s tribe and hometown in Rosebud, South Dakota. (ALSO–today he is releasing “My People Come From the Land,” a track that he worked on in collaboration with a Lakota language teacher and is his debut of playing the Native flute.)

PODS

Cherokee scholar Adrienne Keene (@NativeApprops) and Swinomish and Tulalip photographer Matika Wilbur (@matikawilbur) host the All My Relations Podcast. Their podcast bridges Keene’s expertise in the history of appropriations of Native culture and Wilbur’s interest in the modern for a truly delightful podcast. Their guests include academics, tribal elders, creatives, aunties, and artists. Their latest episode, “Beyond Blood Quantum” features Charlotte Logan, Gabe Galanda, Tommy Miller, and David Wilkins, and discusses the tribal implications, legal basis, and colonial origins of blood quantum.

Rick Harp (Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation) hosts Media Indigena, with regular roundtable guests Candis Callison, Brock Pitawanakwat, Kim TallBear, and Kenneth T. Williams. The scholars, journalists, and policymakers discuss the latest developments in North American news and the direct impact on Indigenous peoples in the 21st century. The conversations are pointed and nuanced. Each guest brings their expertise and insight into the complex issues facing Indian Country. Their latest episode, which was recorded live in Edmonton, Alberta, is called “Is the Green Movement Still Too White?” and looks at the global green movement, the media attention that propelled Greta Thunberg into the spotlight, and some of the pushback from Native Twitter.

This Land, a Crooked Media podcast hosted by Rebecca Nagle (Cherokee Nation) is especially timely. Nagle unpacks how a 20-year-old murder case in Oklahoma made it to the Supreme Court in 2019, the history of land divisions in Indian Territory, the Trail of Tears, and the long-term ramifications for tribal sovereignty and Native land rights.

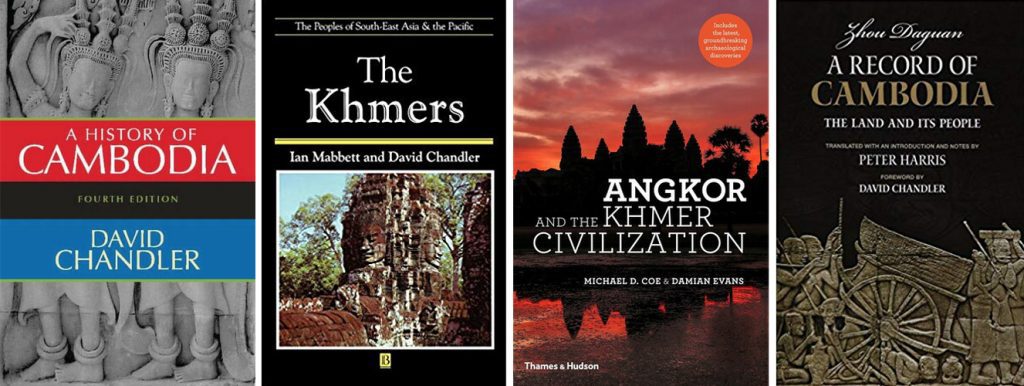

BOOKS & BOOKLISTS

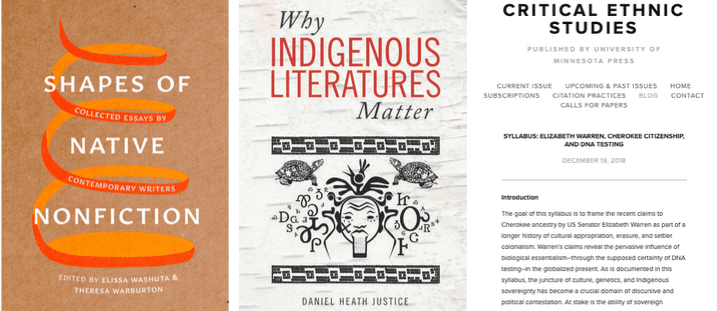

Shapes of Native Nonfiction: Collected Essays by Contemporary Writers (2019) is edited by Elissa Washutta and Theresa Warburton. This is one of the best books I’ve read as a graduate student and holds a permanent place on my shelf. The collection was composed with care and intention. As the editors described it, Shapes of Native Nonfiction is meant to hold structure throughout like a basket. The collection is structured in four terms based on the basket metaphor: technique, coiling, plaiting, and twining. Each represents a different style of non-fiction writing The editors and contributors are speaking directly to the idea that the academic essay is the only valid form of nonfiction. Form here is critical to the decolonial process. The editors write, “our focus on form-conscious Native nonfiction insists on knowledge as a resource whose coercive extraction is used to narrate settler colonialism in order to normalize its structure.”(11). It is a phenomenal collection specific to individuals, peoples, and places.

Daniel Heath Justice’s Why Indigenous Literatures Matter calls into question basic assumptions about what makes up Indigenous literature and, as the title states, why they matter. Justice’s work urges readers to expand their view of what should be considered “Indigenous Literature.” This work is accessible to the generalist and the specialist, yet acknowledges their added significance: “our literatures are just one more vital way that we have countered those forces of erasure and given shape to our own ways of being in the world…they affirm Indigenous presence– and our present.” (xix)

The Elizabeth Warren Syllabus, which seems to become timelier every year, combines the specialties of several scholars already mentioned and citizens of the Cherokee Nation: Adrienne Keene (@nativeapprops), Rebecca Nagle (@rebeccanagle), and Joseph M. Pierce (@pepepierce). The syllabus was meant to not only address Presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren’s claims to Cherokee ancestry but to contextualize the history of such claims by non-natives to Native ancestry. The Syllabus is structured by theme and topic and generally touches on the ideas of DNA and genetic testing, Indigenous citizenship, Cherokee history, erasure, cultural appropriation, blood, and tribal sovereignty. The syllabus was published in the Journal of Critical Ethnic Studies.

Finally, one way to observe Indigenous Peoples’ Day is to support the UT Native American and Indigenous Studies program and institutions that support Native students. Show up to events. Rally around causes. The NAIS Program provides an undergraduate certificate and graduate portfolio for UT students and also hosts a number of speaker series and workshops. This semester’s lineup includes Angelo Baca (Hopi/Diné), Tiya Miles, Héctor Nahuelpan (Mapuche), and Roxana Miranda Rupailaf (Mapuche). Consider attending one or several of these events.

Happy Indigenous Peoples’ Day!

Related Links:

- Kū Haʻaheo Music Video

- Young climate activists working with Greta Thunberg you should know

- Red New Deal

- Red Nation Podcast (They are relaunching on Indigenous Peoples’ Day with 3 new episodes!)

- The 184-Year-Old Promise to the Cherokee Congress Must Keep

- A Tribe Called Red

- Tanya Tagaq

- Frank Waln’s Treaties

- Billy Ray Belcourt’s This Wound Is a World

- Abigail Echo-Hawk on the art and science of ‘decolonizing data’

- IllumiNative

- Native Appropriations

- #HonorNativeLand: A Guide and Call to Acknowledgement

You might also like:

Authorship and Advocacy: The Native American Petitions Dataverse by Alina Scott

Who Put Native American Sign Language in the US Mail? by Jennifer Graber

For Native Americans, Land Is More Than Just the Ground Beneath Their Feet by Kelli Mosteller

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.