During the summer of 2016, we will be bringing together our previously published articles, book reviews, and podcasts on key themes and periods in the history of the USA. Each grouping is designed to correspond to the core areas of the US History Survey Courses taken by undergraduate students at the University of Texas at Austin.

Based in a border state, the historians at UT Austin are in a good position to offer historical perspectives on the Mexican-US borderlands. Below we have compiled a selection of articles on this topic previously published on NEP. These insights add much needed context to counter studies that separate the history of the US and Mexico in to distinct categories.

To start, Anne Martínez contextualizes the economic ties between the United States and Mexico during the twentieth century and discusses the ways Salman Rushdie and Sebastião Salgado conceptualize the US-Mexico borderlands.

The Mexico-US border is often talked about as a religious frontier dividing the Catholic South from the Protestant North. However, as Anne Martínez shows, Catholics on both sides of the border were very much part of the history of Mexico-US interactions. Read more about the Catholic borderlands between 1905 and 1935 and a list of recommended further reading.

The Mexican Revolution knew no borders. People quite freely moved between Texas and Mexico as Lizeth Elizondo highlights in her review of Raul Ramos’ War Along the Border: The Mexican Revolution and the Tejano Communities.

The “War on Drugs” often dominates discussions about Mexican-American relations. UT graduate student Edward Shore broadens the discussion to a global level arguing that the violence, disorder, and political, social, and economic instability associated with the drug trade has a long history with repercussions across the world.

And Christina Villareal recommends A Narco History: How the United States and Mexico jointly created the Mexican Drug War, by Carmen Boullosa and Mike Wallace (OR Books, 2015)

While relations between Mexico and the United States are commonly discussed in negative terms, this has not always been the case. Emilio Zamora’s book Claiming Rights and Righting Wrong in Texas highlights the most cooperative set of relations in US-Mexican. Could this serve as a model for what is possible?

Over the past few years the Texas State Historical Association (TSHA) has increasingly focused on the history of Mexican Americans living in the state. History Professors Emilio Zamora, University of Texas, and Andrés Tijerina, Austin Community College, are co-editing the forthcoming Tejano Handbook of Texas. And Dr Cynthia E. Orozco discusses the increased presence of Latinas and Latinos at the 2015 meeting of the TSHA.

Policing the Mexican-American border is not a new issue. Christina Salinas discusses the Texas Border Patrol and the social relations forged on the ground between agricultural growers, workers, and officials from the U.S. and Mexico during the 1940s.

From 15 Minute History:

In the late 17th century, Native American groups living under Spanish rule in what is now New Mexico rebelled against colonial authorities and pushed them out of their territory. In many ways, however, the events that led up to the revolt reveal a more complex relationship between Spanish and Native American than traditional histories tell. Stories of cruelty and domination are interspersed with adaptation and mutual respect, until a prolonged famine changed the balance of power.

In the late 17th century, Native American groups living under Spanish rule in what is now New Mexico rebelled against colonial authorities and pushed them out of their territory. In many ways, however, the events that led up to the revolt reveal a more complex relationship between Spanish and Native American than traditional histories tell. Stories of cruelty and domination are interspersed with adaptation and mutual respect, until a prolonged famine changed the balance of power.

Guest Michelle Daneri helps us understand contemporary thinking about the ways that Spanish and Native Americans exchanged ideas, knowledge, and adapted to each others’ presence in the Southwest.

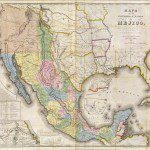

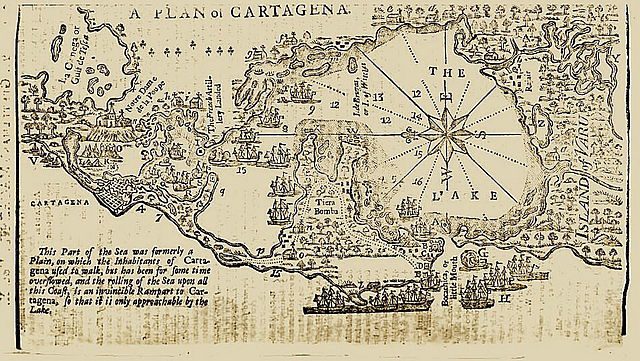

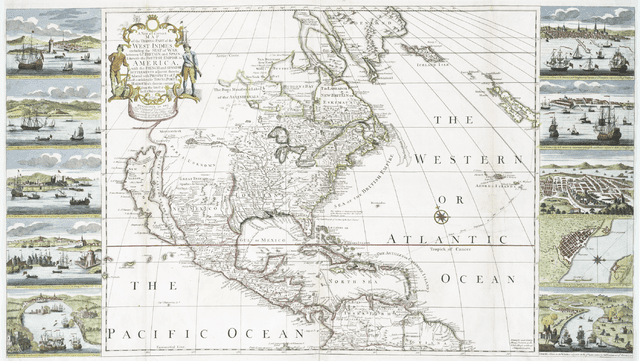

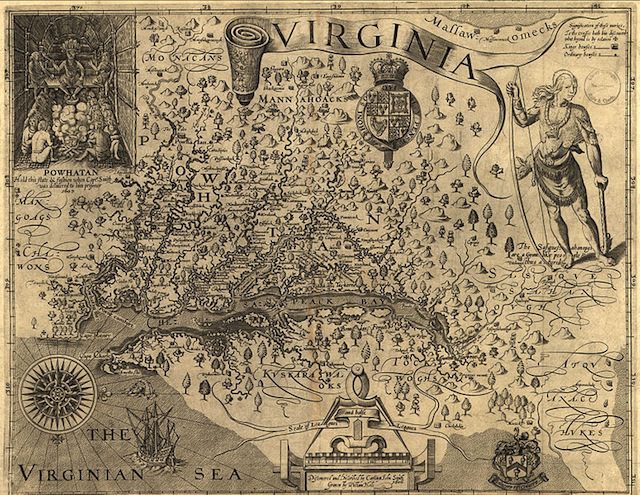

Mapping Perspectives of the Mexican-American War

This episode looks at US perceptions of Mexico through map making during the US / Mexico War, in which a private publisher sold maps that were reissued annually to reflect ongoing progress in the campaign. Intended for a general, popular audience, these maps served as propaganda in aid of the conflict, but historians and military analysts alike have ignored them until recently—even though they may well have influenced the positioning of the border at the war’s end.

This episode looks at US perceptions of Mexico through map making during the US / Mexico War, in which a private publisher sold maps that were reissued annually to reflect ongoing progress in the campaign. Intended for a general, popular audience, these maps served as propaganda in aid of the conflict, but historians and military analysts alike have ignored them until recently—even though they may well have influenced the positioning of the border at the war’s end.

Guest Chloe Ireton looks at the intriguing history of maps as propaganda and the role of two publishing houses—J. Disturnell and Ensigns & Thayer—not only in rewriting the history of the Mexican-American war, but in influencing the outcome of the war even as it was still ongoing.

The words “Mexican immigration” are usually enough to start a vibrant, politically and emotionally charged debate. Yet, the history of Mexican migration to the U.S. involves a series of ups and downs—some Mexicans were granted citizenship by treaty after their lands were annexed to the U.S., and, until the 1970s, they were considered legally white—a privilege granted to no other group. At the same time, Mexicans crossing the border every day were subjected to invasive delousing procedures, and on at least two occasions were subjected to incentivized repatriation.

Guest Miguel A. Levario from Texas Tech University (and a graduate of UT’s Department of History!) walks us through the “schizophrenic” relationship between the US and its southern neighbor and helps us ponder whether there are any new ideas to be had in the century long debate it has inspired—or any easy answers.

In the early part of the 20th century, Texas became more integrated into the United States with the arrival of the railroad. With easier connections to the country, its population began to shift away from reflecting its origins as a breakaway part of Mexico toward a more Anglo demographic, one less inclined to adapt to existing Texican culture and more inclined to view it through a lens of white racial superiority. Between 1915 and 1920, an undeclared war broke out that featured some of the worst racial violence in American history; an outbreak that’s become known as the Borderlands War.

Guest John Moran Gonzalez from UT’s Department of English and Center for Mexican American Studies has curated an exhibition on the Borderlands War called “Life and Death on the Border, 1910-1920,” and tells us about this little known episode in Mexican-American history.

At 2:30 pm on Saturday September 21 1969, US president Richard Nixon announced ‘the largest peacetime search and seizure operation in history.’ Intended to stem the flow of marijuana into the United States from Mexico, the three-week operation resulted in a near shut down of all traffic across the border and was later referred to by Mexico’s foreign minister as the lowest point in his career.

Guest James Martin from UT’s Department of History describes the motivations for President Nixon’s historic unilateral reaction and how it affected both Americans as well as our ally across the southern border.

Colonial Connections and Entangled Histories:

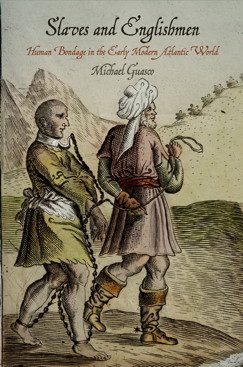

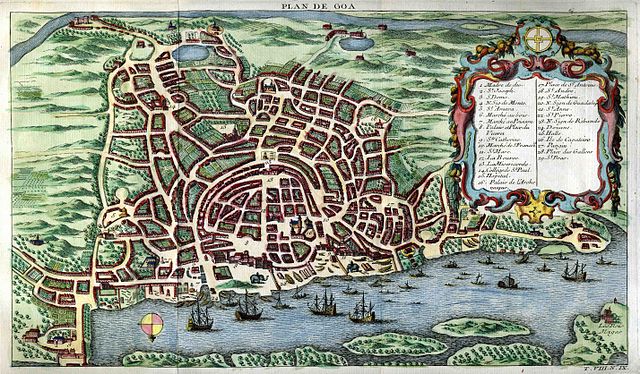

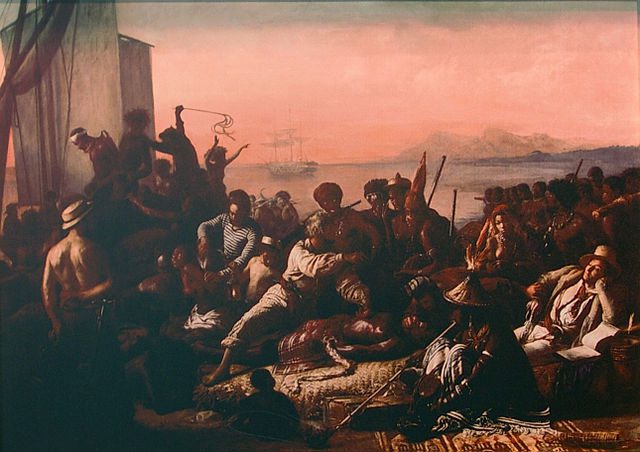

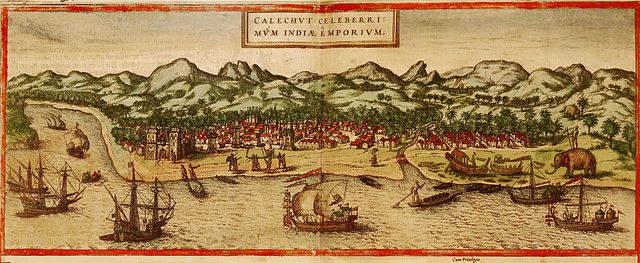

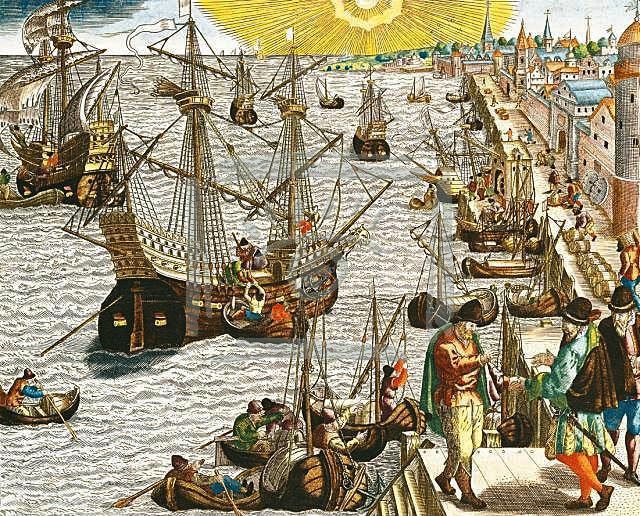

The history of Mexican-American relations extends back into colonial history as Not Even Past’s series on the Entangled Histories of the Early Modern British and Iberian Empire and their Successor Republics demonstrates. Start with Bradley Dixon’s excellent introduction Facing North From Inca Country: Entanglement, Hybridity, and Rewriting Atlantic History and then explore the following:

- Christopher Heaney reviews Poetics of Piracy: Emulating Spain in English Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) by Barbara Fuchs

- Jorge Esguerra-Cañizares discusses his book Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-170 (Stanford University Press, 2006).

- Renata Keller discusses Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 (Yale University Press, 2007) by J.H. Elliott

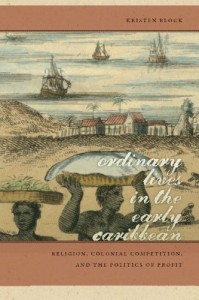

- Ernesto Mercado Montero discusses Ordinary Lives in the Early Caribbean: Religion, Colonial Competition, and the Politics of Profit, by Kristen Block (2012)

- Mark Sheaves reviews Francisco de Miranda: A Transatlantic Life in the Age of Revolution 1750-1816, by Karen Racine (2002)

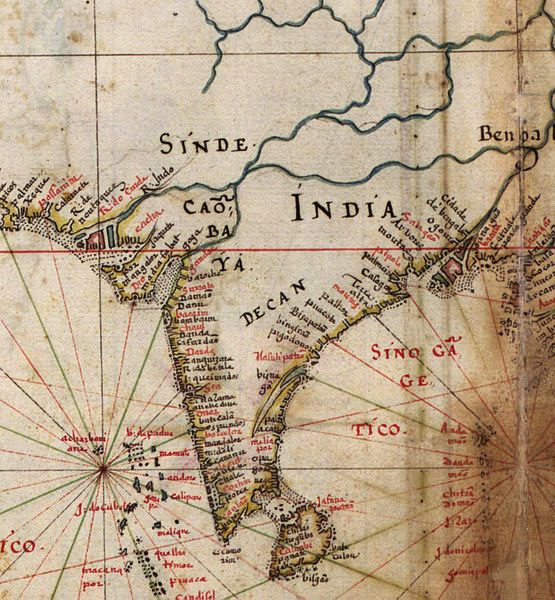

- Ben Breen recommends Explorations in Connected History: from the Tagus to the Ganges (Oxford University Press, 2004), by Sanjay Subrahmanyam

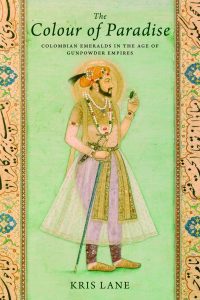

- Maria José Afanador-Llach recommends Colour of Paradise: The Emerald in the Age of Gunpowder Empires, by Kris Lane (2010)

- And finally, Jorge Cañizares Esguerra recommends Felipe Fernández-Armesto’s Our America: A Hispanic History of the United States (2014).

![Description des Indes Occidentales [Description of the West Indies]. Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas. Amsterdam: M. Colin, 1622. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)](http://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/tordes.jpg)