by Shery Chanis

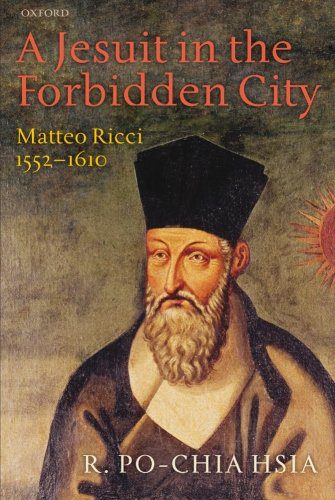

Hsia’s book on Matteo Ricci expands the traditional narratives of the Age of Expansion and transforms our understanding of them. Beyond the Mediterranean and Atlantic worlds, early modern Europeans, Jesuits among them, also ventured to Asia. Published on the four-hundredth anniversary of Matteo Ricci’s death, Ronnie Hsia’s biography of the Jesuit also marks part of a larger effort to commemorate one of the most important figures in the history of Christianity in China. In addition, this book shows a shift in focus to China by Hsia, who has produced an abundance of works on German social and cultural history during the Reformation era.

Hsia departs from other Ricci biographies with a more down-to-earth and rounded portrayal of the Jesuit missionary. Rather than claiming Ricci to be a saint or a pioneer cultural accommodationist who allowed Chinese converts to continue certain Chinese rituals, Hsia examines the context in which Ricci operated in two new ways. First, Hsia includes many other Jesuits in his book, illustrating that Ricci was part of a greater effort of the China Mission. Hsia discusses many Chinese figures along Ricci’s path, some of whom helped the Jesuit mission, some debated with the Jesuit, some were converted, and some collaborated with Ricci on various works. Second, Hsia discusses Ricci’s emotions at various stages of his mission. Although Ricci was highly successful in China, Hsia shows that he also experienced melancholy and sadness in his tenure in China.

Hsia departs from other Ricci biographies with a more down-to-earth and rounded portrayal of the Jesuit missionary. Rather than claiming Ricci to be a saint or a pioneer cultural accommodationist who allowed Chinese converts to continue certain Chinese rituals, Hsia examines the context in which Ricci operated in two new ways. First, Hsia includes many other Jesuits in his book, illustrating that Ricci was part of a greater effort of the China Mission. Hsia discusses many Chinese figures along Ricci’s path, some of whom helped the Jesuit mission, some debated with the Jesuit, some were converted, and some collaborated with Ricci on various works. Second, Hsia discusses Ricci’s emotions at various stages of his mission. Although Ricci was highly successful in China, Hsia shows that he also experienced melancholy and sadness in his tenure in China.

After a creative prologue about Ricci’s death and burial, Hsia outlines Ricci’s life, from his birth in Macerata, Italy to his burial in Beijing, China. Hsia traces Ricci’s education and training in Europe and his journey to Asia before settling in China. Hsia devotes a chapter to each Chinese city where Ricci lived – Macao, Zhaoqing, Shaozhou, Nanchang, Nanjing, and Beijing –to illustrate Ricci’s northward movement within the Chinese empire moving towards the capital, his ultimate goal. Hsia follows this with a discussion of The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven, which he argues is Ricci’s most important work. Hsia concludes his book with an Epilogue, witha brief historiography of works on Ricci in the four centuries since his death, from Nicholas Trigault to Jonathan Spence to Chinese scholars including Lin Jinshui and Sun Shangyang.

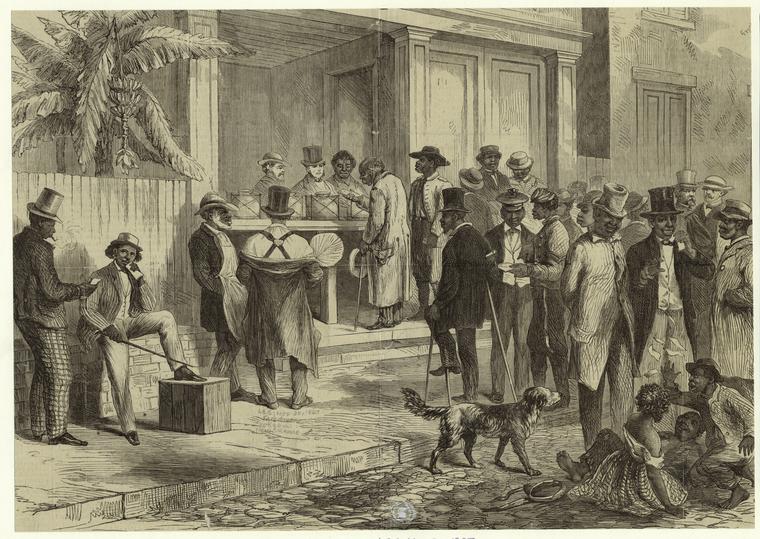

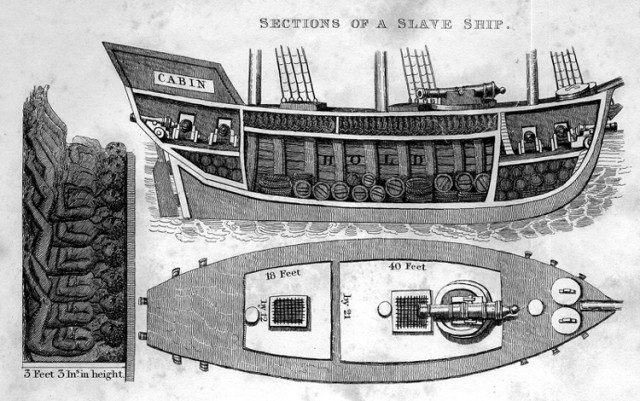

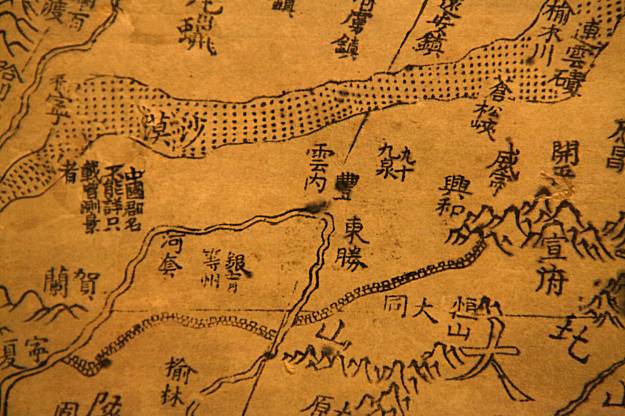

Detail from the China section of Matteo Ricci’s 1602 map, the “Impossible Black Tulip of Cartography” (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

Hsia’s innovative approach continues with his attention to Michele Ruggieri, Ricci’s fellow Italian Jesuit and partner at the beginning of the Jesuit mission in China. Not only does Hsia devote an entire chapter to Ruggieri, he also includes a legal case against Ruggieri in his appendix. Hsia’s inclusion of Ruggieri, who is usually seen only in Ricci’s shadow, helps expand our knowledge of the Jesuit mission in China.

Hsia’s increasing focus on China in his scholarship is also reflected in his incorporation of many Chinese sources in his book. In addition to Ricci’s extant letters and published works, Hsia includes such Chinese materials as local gazetteers, tax records, poems, and letters. This offering of a more balanced perspective between Europe and China makes his focus and methodology less Eurocentric, which is also a strength of this book. Hsia’s inclusion of photographs he has taken in some of the cities Ricci had lived also serves as a great addition to the book.

Hsia’s micro-historical approach of focusing on one Jesuit does not provide a full account of the Jesuit mission in China which can be viewed as a weakness of the book. In addition, the book title might be somewhat misleading, since Hsia is interested in not only Ricci in Beijing, the Forbidden City, but also in other places. Nonetheless, Hsia has provided an intriguing account of an important figure in the Jesuit China mission who was also part of the larger narrative of the Age of Expansion.