By Chris Babits

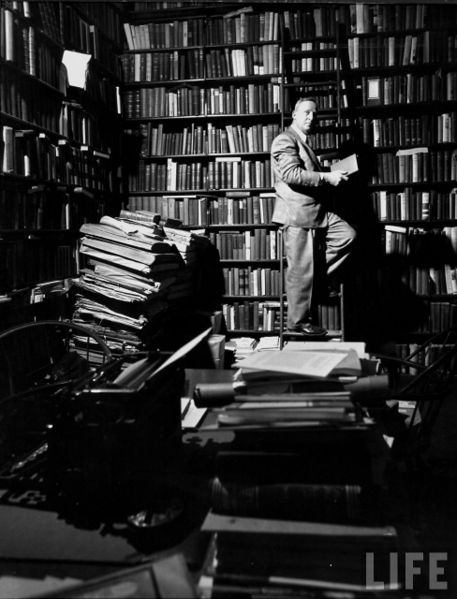

In a May 2016 podcast for the Journal of American History, Yael A. Sternhell said, “For the great majority of [historians], when we walk into an archive, we have this illusion that this is where historical knowledge lies. Raw primary sources. Untainted. Unblemished. Just waiting for us to pick them up and create [a] narrative that will adhere to the history of the topics we’re looking at.” She believes that this is not how we should look at archives. Sternhell challenges historians to think about how papers got to their respective archives, who arranged them, and whether the arrangement of items in special collections and archives affect the stories that historians construct.

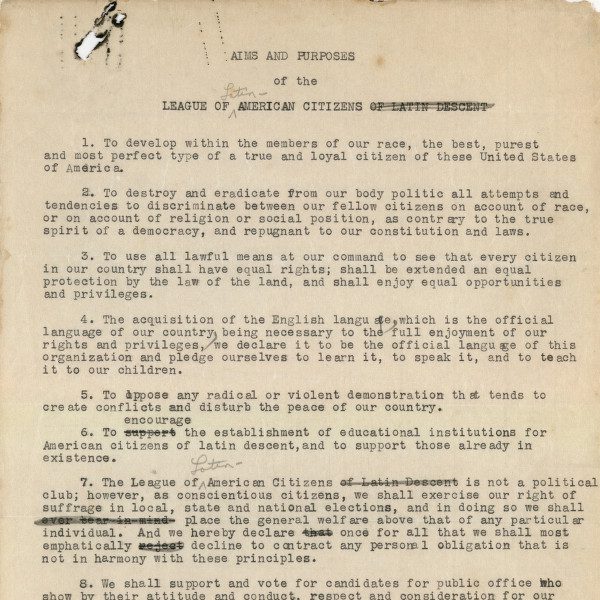

Sternhell’s words resonated with me recently when I went through the collections at the University of North Texas. The first collection was the Resource Center LGBT Collection, which contains 636 boxes of materials about the LGBT movement in Texas. Phil Johnson, the founder of the Dallas Gay Historic Archives, donated many of the materials in this collection. During my two weeks at the University of North Texas, I had come across numerous documents outlining Johnson’s hostility toward organized religion. Johnson blamed religious figures, like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, for creating a hateful social and political environment for the LGBT community. That is why I thought little (at least at first) of coming across a box with a section labeled “Bigots.” This section was right before another titled “Religions.” It seemed likely that Johnson would have made these tags and grouped “Bigots” and “Religions” together.

After talking to Courtney Jacobs, the special collections librarian, I found out that I was wrong. Johnson was not the person who created these section dividers. Instead, Jacobs recognized the handwriting as that of the archivist who had organized and arranged the materials when the collection was being processed. The different handwriting on some of the folders, especially the ones that looked older and as if they had been stored away for some time, should have given this away. But, after talking to Courtney for ten minutes about this particular box, it was clear that someone at the University of North Texas had labeled a group of individuals as “Bigots.” On top of this, they separated these individuals from “Religions,” even though the religious groups or individuals in this section said some of the same things that the “Bigots” said about LGBT persons.

This experience in the archives gets to the heart of Sternhell’s last point: how does the arrangement of items in collections, and the labels they are given, influence the historian’s engagement with those items? Right now, I don’t how much these sectional dividers impacted how I interpreted the materials inside the folders. What I do know is this: sometimes historians are far too eager to get to what’s inside a folder to take the time to notice other clues (like different handwriting). I know I’ve learned some important lessons: slow down; never assume; and ask special collections librarians lots of questions.

![]()

More by Chris Babits on Not Even Past:

The Rise of Liberal Religion, by Matthew Hedstrom (2013)

Encountering America: Humanistic Psychology, Sixties Culture, and the Shaping of the Modern Self, by Jessica Grogan (2012)

Age of Fracture, by Daniel T. Rodgers (2011)

![]()