(This is the first of a series that will explore creative ways to think about historic markers in Austin.)

By Jesse Ritner

1917 marked a turning point in the history of Austin’s development. A large donation and the dismembering of a family estate spread the city west and north, resulting in dramatic increases in public spaces, urban housing, and wealth for the Austin public schools. Yet, Austin’s growth came at the expense of one specific neighborhood. The story is already written onto the city, if we know where to look.

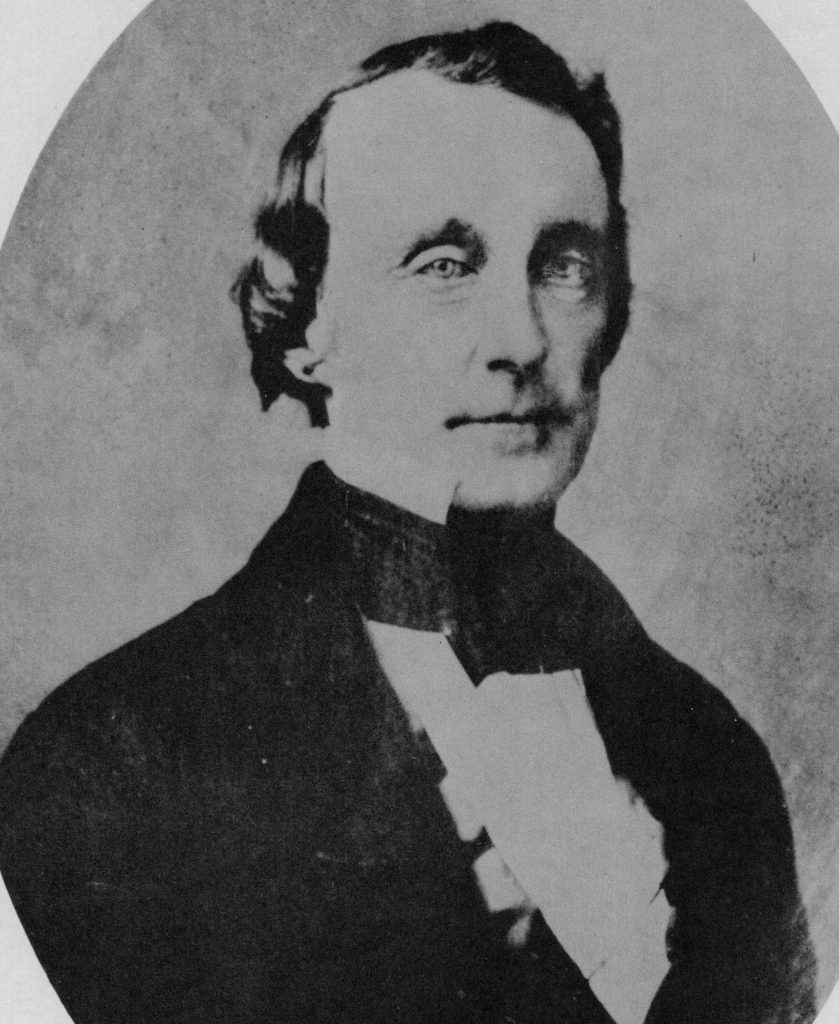

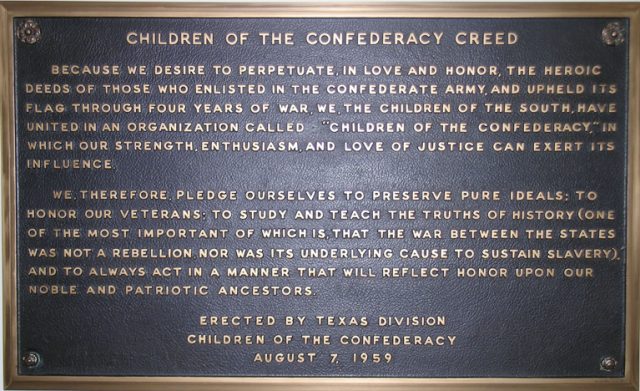

The Andrew Jackson Zilker marker (placed in 2002), the Clarksville Historic District marker (placed in 1973), and the Crusemann-Marsh-Bell House (placed in 2009) seem to be about distinctly different historical events. Zilker’s, located in front of the Barton Springs Pool House, informs us about the life of Austin’s “most worthy citizen” in basic outline, emphasizing his rags to riches story, and his generous philanthropy. The Clarksville marker, on the other hand, recounts a story of survival. It details the resilience of the black community of Clarkville, founded by freed slaves in 1871, who refused to move for over a century, despite repeated pressure from the city of Austin. Last, the Crusemann-Marsh-Bell House marker comments on the architecture of this 1917 home, built by the “granddaughter of Texas Governor E.M. Pease.” By themselves, the three markers recount one story of wealth, one of poverty, and one involving the American Dream. Collectively, they tell a dramatic geographic history of urban expansion into west Austin in 1917.

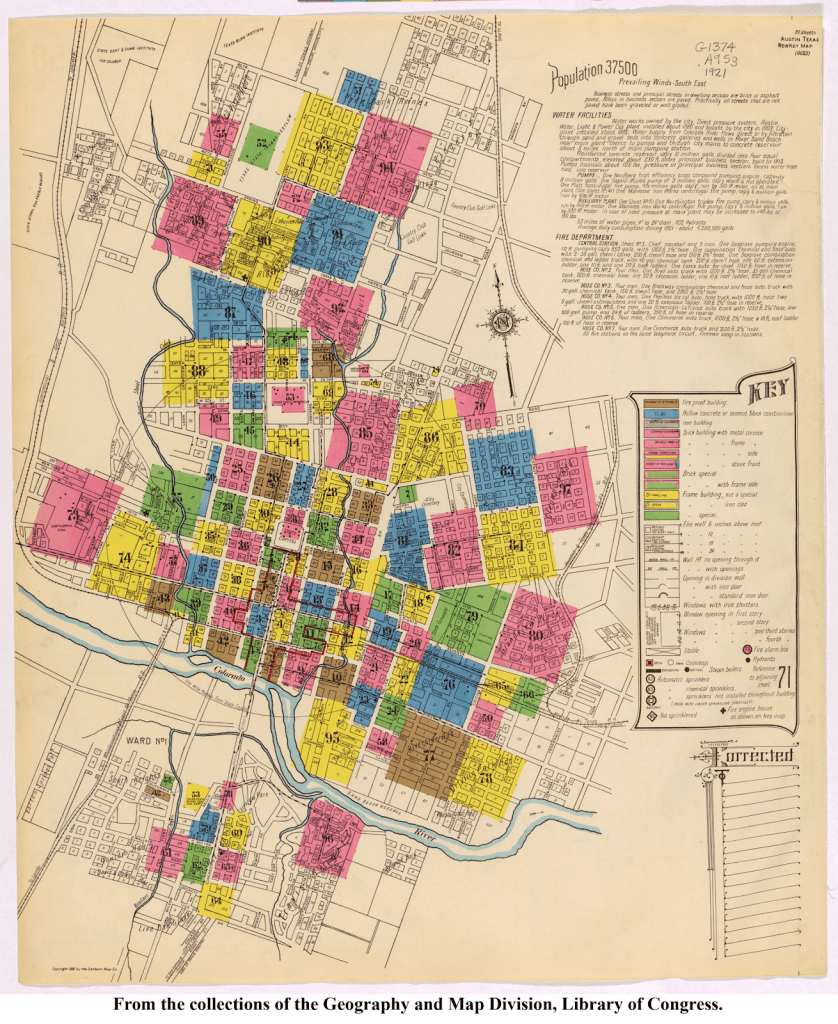

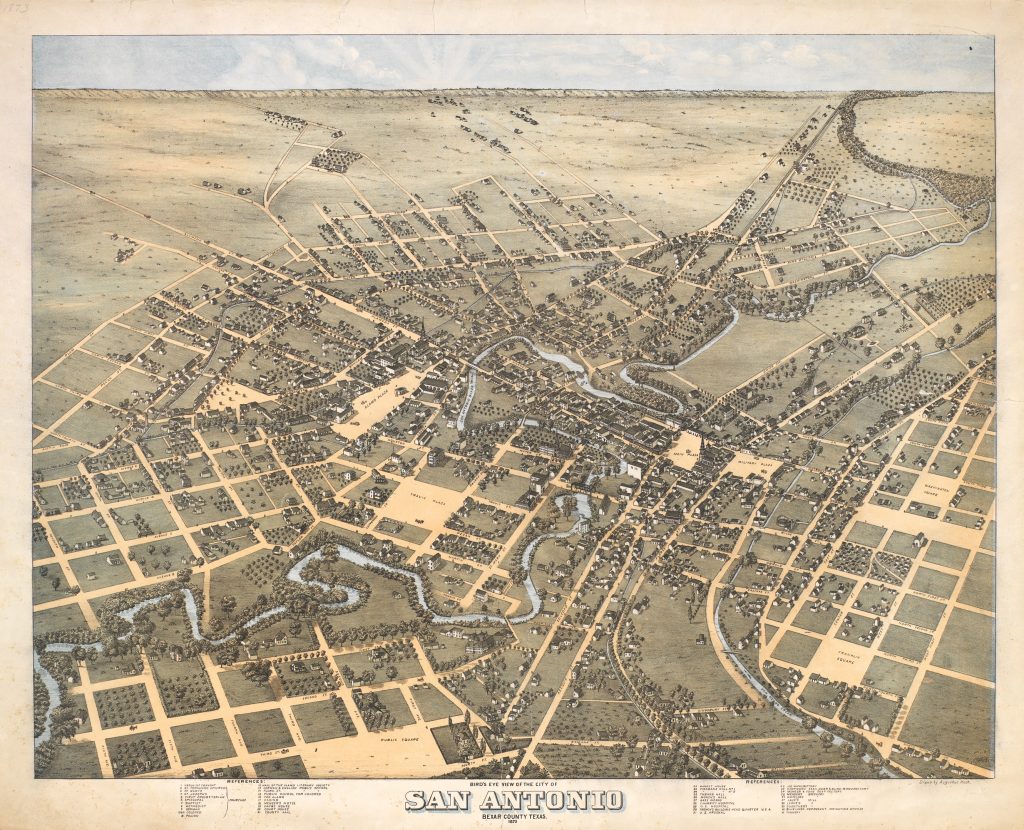

Although the date is missing in the Zilker marker, it notes that Zilker “indirectly funded school industrial programs when he sold 366 acres of parkland, including Barton Springs, to the city.” The sale occurred in 1917. The same year the heirs to the Pease estate, which spread from 12th street to 24th street and from Shoal Creek to the Colorado River, decided to split the estate and develop it, dramatically spreading the city of Austin north and west (marked in black on the map). This house was one of the first homes built in what would become the Enfield development. Comparing the map above to the historic map below (although it is a few years newer), it is easy to see that the black neighborhood of Clarksville (marked in red and bordering the new development), sits precariously between the new park and the burgeoning neighborhood that spread Austin west of Lamar Boulevard.

In 1918, as the Clarksville marker notes, the Austin School Board closed down the Clarksville public school in one of the first attempts to move Clarksville residents east. The decision by Austin’s school board, only a year after the single largest donation in their history, was not accidental. The absorption of what is now Zilker Park and the Pease Estate into Austin pushed city borders westward, pulling Clarksville undoubtedly into the urban sphere. The presence of a black neighborhood on the border of the soon to be wealthy and white neighborhood north of 12th street with the easy access to Zilker Park made their movement politically imperative in Jim Crow era Austin.

While the two years of 1917 and 1918 seem almost happenstantial in each individual marker, when read together they mark a significant turning point in Austin’s growth, as well as a distinct moment in Austin’s history of segregation.

Also in this series:

Mapping Austin’s Historical Markers

Similar series:

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.