Who actually lived in The Adirondacks, Yosemite, and The Grand Canyon before they became national parks? This is the simple, but compelling, question Karl Jacoby asks in Crimes against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation. When we think about preserving nature, Jacoby argues, Americans tend to assume an easy dichotomy between The Evil Poacher vs. The Righteous Park Ranger. But Crimes against Nature tells a deeper history of the rural communities who relied on these lands before their “preservation” and introduces some moral complexity into the story of America’s national parks.

Who actually lived in The Adirondacks, Yosemite, and The Grand Canyon before they became national parks? This is the simple, but compelling, question Karl Jacoby asks in Crimes against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation. When we think about preserving nature, Jacoby argues, Americans tend to assume an easy dichotomy between The Evil Poacher vs. The Righteous Park Ranger. But Crimes against Nature tells a deeper history of the rural communities who relied on these lands before their “preservation” and introduces some moral complexity into the story of America’s national parks.

Jacoby’s narrative starts with the legal, cultural and environmental changes taking place during the Progressive Era. As America became increasingly urbanized, many social reformers and politicians feared a dystopian future in which crowded, industrial cities replaced nature entirely. Teddy Roosevelt often spoke about the dangers of “over-civilization” as fewer and fewer Americans encountered the great outdoors. Starting in the late 19th-century, The federal government responded to these anxieties with the establishment of national parks that would protect “wilderness” from human development. These preserved park lands, officials reasoned, would encourage people to “get back to nature” and escape the pollution, disease, and social disorder of urban slums.

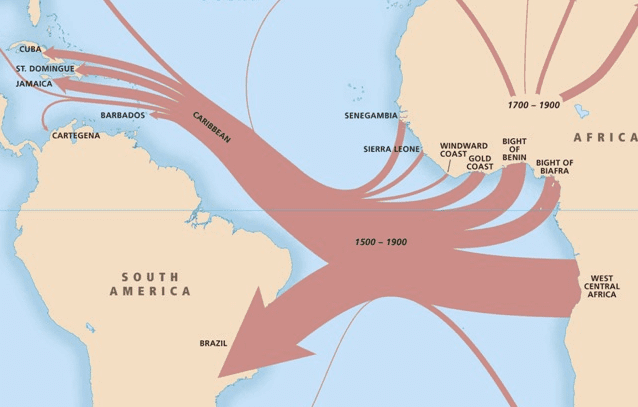

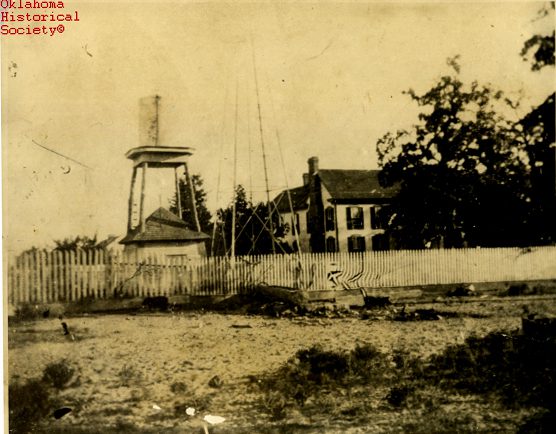

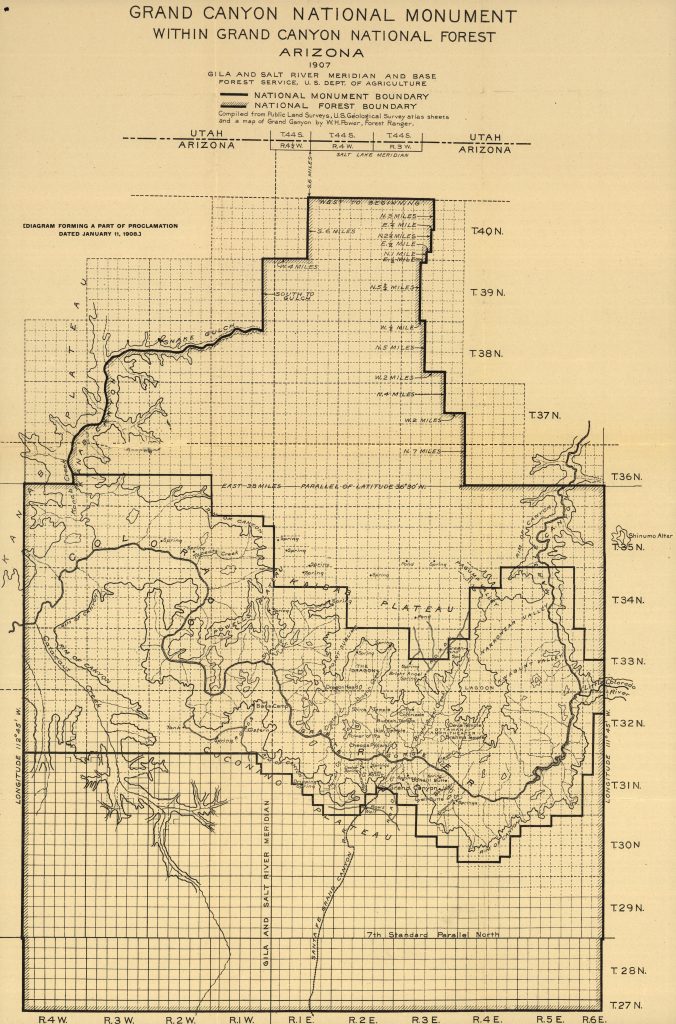

But the conservationist impulse to protect “wilderness” from the encroachment of human society, Jacoby points out, wholly disregarded the rural communities that had been living there for generations. Overnight, settlers and residents became outlaws and “squatters” residing on government owned land. The hunting and fishing which had sustained those communities was suddenly “poaching,” a crime that could result in fines or banishment. At the time of the Adirondacks’ preservation, 16,000 settlers lived within what became “preserved” and “uninhabited” land. Even the Grand Canyon at one time provided trails and access to natural resources for local Native American populations.

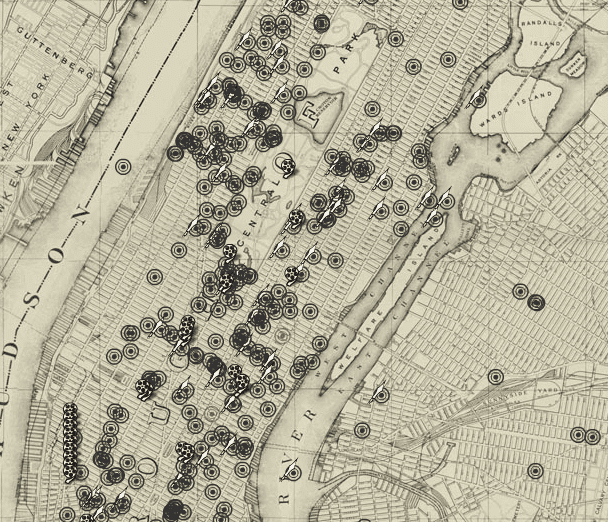

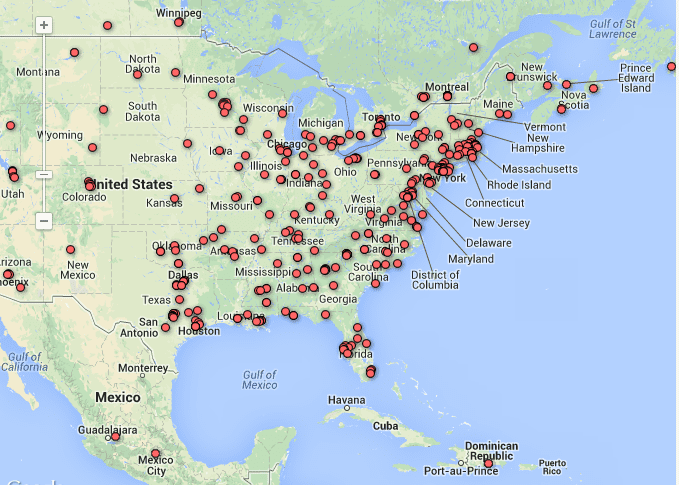

Map of Grand Canyon National Monument prepared by the National Forest Service, 1907 (Library of Congress)

In order to enforce these new sets of rules, federal and state governments mobilized a bureaucracy of Forest Police to prevent squatting and poaching. Officials set new legal boundaries around “conserved” areas and organized forestland into grids of property ownership. Jacoby argues these efforts to define and protect “preserved” zones oversimplified complex ecological systems and produced unintended consequences. When officials at Yellowstone began hunting predators such as coyotes and mountain lions to maintain animal populations, the number of elk soared, throwing off the park’s delicate ecological balance. Despite the conservationist impulse to preserve nature as it is, park managers were really creating “nature” as it ought to be.

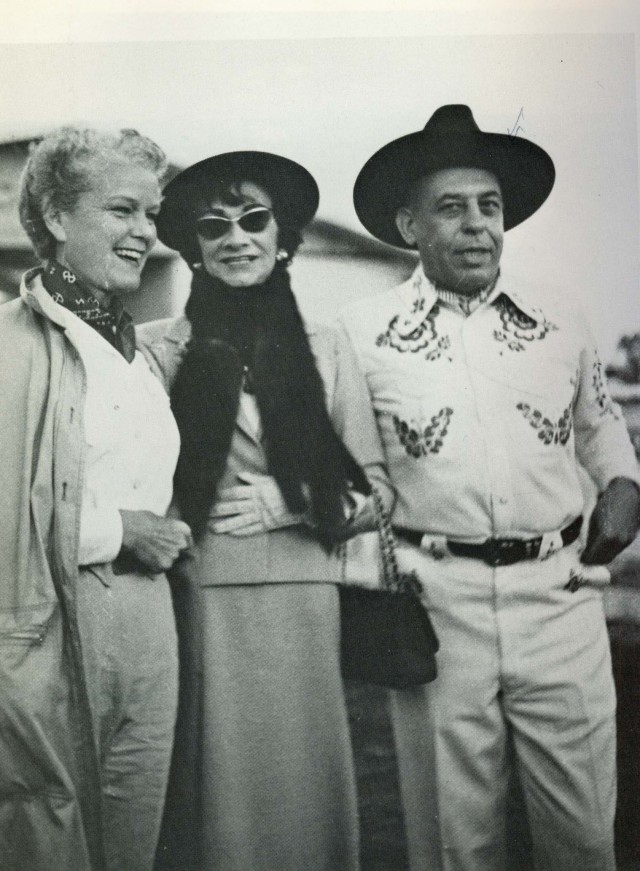

Horace M. Albright, Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, with bears from the park, 1922 (National Park Service)

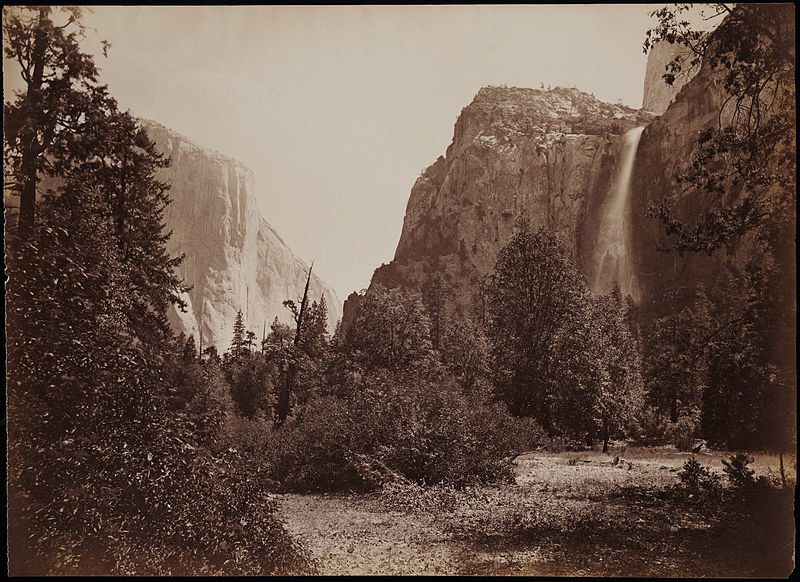

Crimes against Nature also details a variety of confrontations that ensued between park officials and the local communities who refused to leave. Setting fires, hunting or even making violent threats all represented forms of resistance against the incursions of the state on rural lands. Although many conservationists regarded these rural populations as fascinating vestiges of a pre-modern world, that nostalgia co-existed with a fierce contempt for their “primitive” modes of subsistence. Conservationists and Forest Police railed against the “irrationality” and wastefulness of rural hunting habits and worried that such behavior would undermine the rule of law.

“View of Tutocanula Pass, Yosemite, California,” by photographer Carleton E. Watkins, 1878-1881 (Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Jacoby concludes that both sides actually embodied distinct, but complementary, American ideals. While conservationists sought to prevent illicit behavior and maintain the rule of law, settlers regarded themselves as rugged individualists pursuing self-sufficiency. In contrast to the simplified narrative of conservation vs. poaching, Jacoby sees a morally complex story unfolding in the wilderness.

Read more on the history of national parks and preservation:

Neel Baumgartner on Big Bend’s “scenic beauty”

Erika Bsumek on Lady Bird Johnson’s beautification project

And watch Blake Scott and Andres Lombana-Bermudez’s short documentary on the history of tourism in the Panamanian jungle