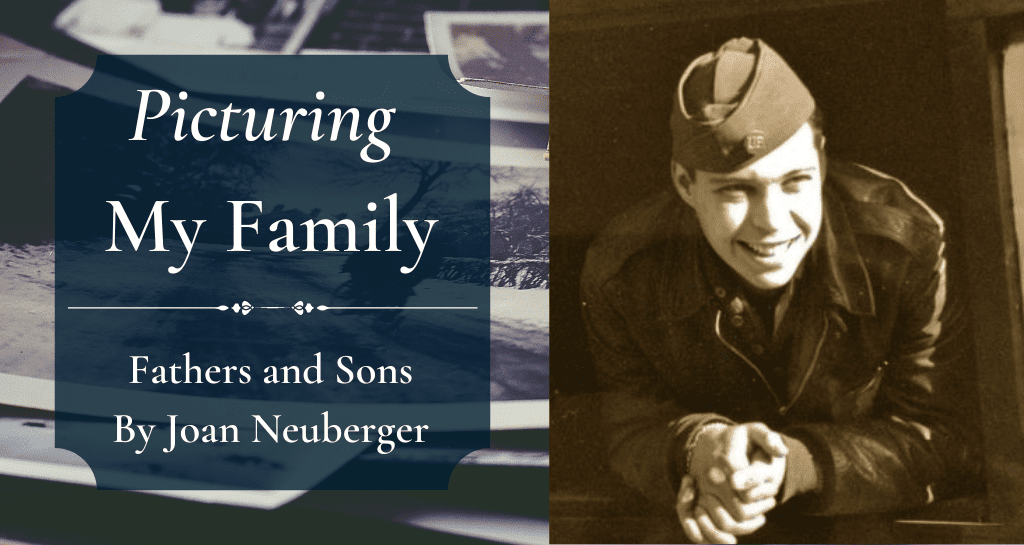

From the Editors:

“Picturing My Family” is a new series at Not Even Past. As a Public History magazine, we aim to make History more accessible by publishing research features and other articles. But of course, History doesn’t reach us solely through words. It lives on in images, too. A good photograph transmits as much information as a line of text, and it does so in an extraordinarily evocative way. Dispensing with description, photography brings us face to face with the past. Visual cues can stimulate our sensory imagination and present us with surprising new details, encouraging us to ask questions, to dig deeper, and to think like historians.

Our concept is simple. We invite Not Even Past readers to:

• Send us a photograph of a family member or ancestor. The photograph doesn’t have to be old; it could be from any period. The subject can be one of your grandparents, a cousin, a distant relative – anyone whom you count as part of your family.

• Tell us in less than 250 words what the image shows and why it’s meaningful for you and your family. If you wish, you can set the photo in historical context, too. But that isn’t necessary.

If you are interested in submitting something for this series, please click here.

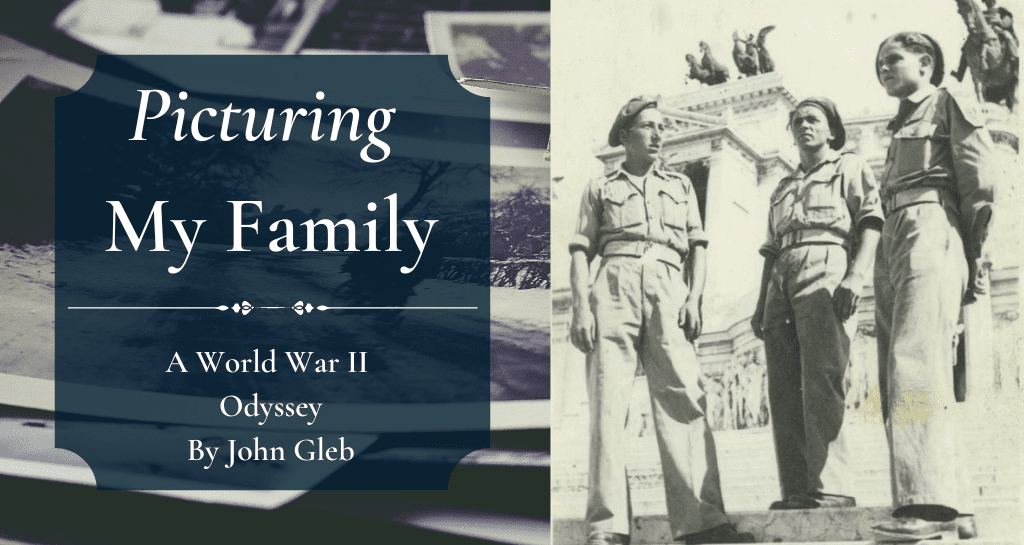

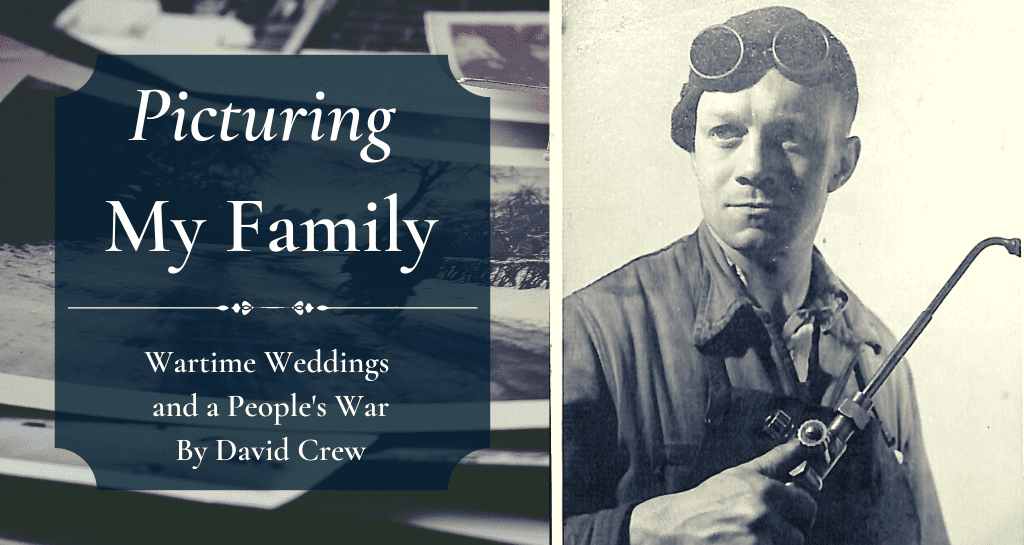

In this instalment of “Picturing My Family,” historian David Crew shares two photographs that highlight different aspects of life on the home front during World War II. Crew’s contributions remind us that the impacts of war reverberate far from the front lines, creating profound disturbances and opening new opportunities for civilians as well as soldiers.

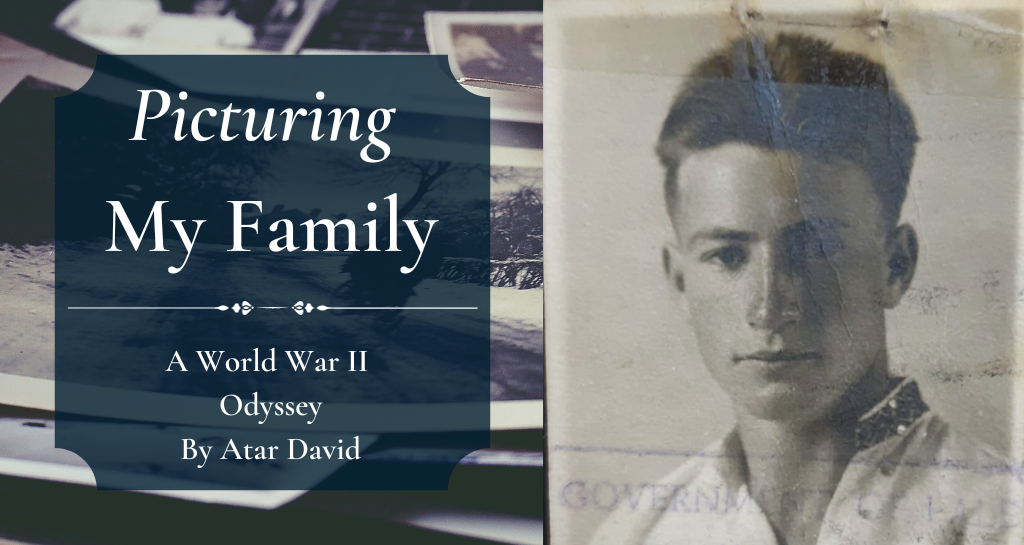

A Wartime Wedding

By David Crew

This is a photograph of my parents’ wedding in London in September 1939. The Second World War had just begun with the German invasion of Poland, but this was still the period known as the “Phony War” with no major land battles in Western Europe and an uneasy quiet. It was not until May 1940 that the Germans invaded and subsequently defeated France. Britain had counted on the formidable French Army being able to halt the German Blitzkrieg. But when the French sued for an armistice just six weeks after the invasion, the British Expeditionary Force had to retreat across the Channel. It would be almost four years (June 6th,1944) before British soldiers could set foot on French soil again, now as one component of a huge multi-national invasion force.

When I first saw this photograph, I was struck by how normal it all seemed—until I asked my aunt Joan, shown here at the front left, what was in the square, white bag she was holding in her left hand. She told me that it was a gas mask. In the 1930s, many Europeans feared that in the next war enemy planes would drop poison gas on major cities, killing large numbers of civilians. By the time this wedding photograph was taken, the British authorities had distributed millions of gas masks to the population. But the Germans never dropped poison gas on British cities.

A People’s War

By David Crew

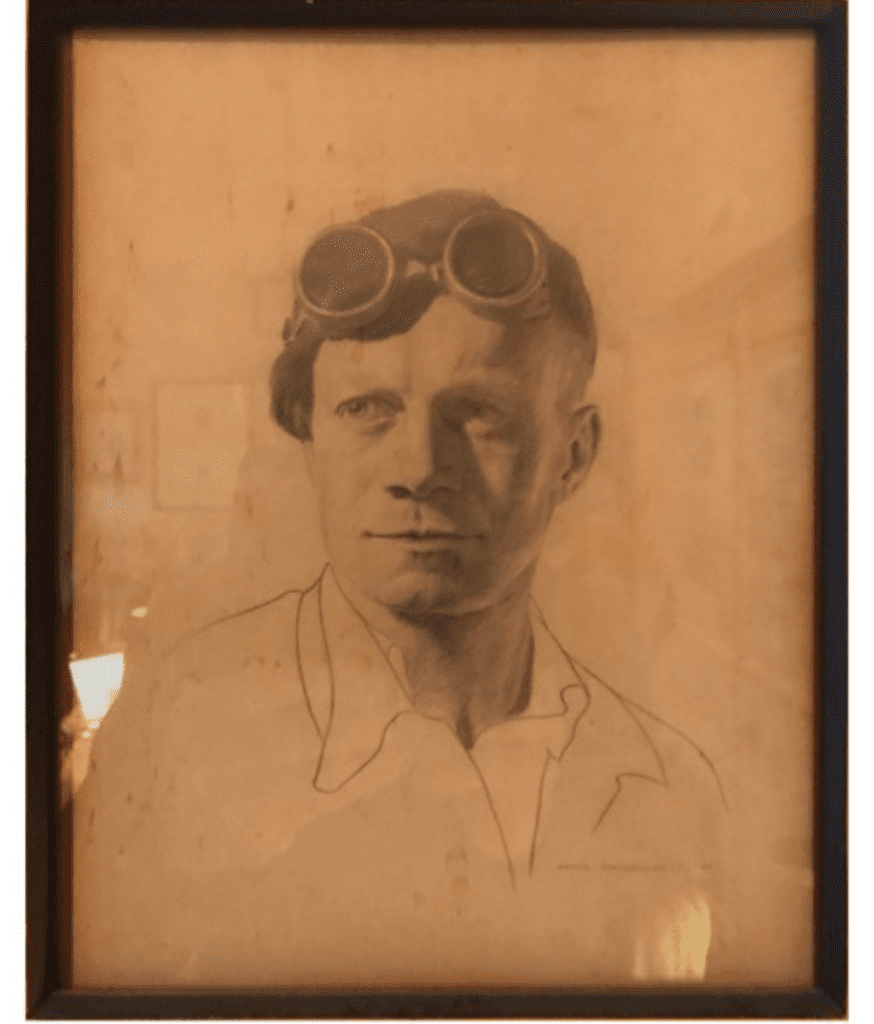

World War II was a People’s War in which millions of women and men around the globe were mobilized to produce massive numbers of planes, tanks, and guns as well as to fight. This photograph shows my mother’s brother who worked as a welder in British war industry. To escape the German bombing of London, the firm that employed my uncle was evacuated to Melton Mowbray, a small town in Leicestershire. The photograph was probably taken by a professional photographer.

An artist then used this photograph to draw the following still-incomplete sketch of my uncle. It may have been intended as the first step in the development of a poster to support the war effort.

David Crew is a Distinguished Teaching Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin. He has taught at UT since 1984 and has been a faculty member of the Frank Denius Normandy Scholar Program on World War Two since 1993. His current book project is Disturbing Images: Photographing Hitler’s Third Reich,1933–1945.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.