By Daina Ramey Berry, University of Texas at Austin

(This article was originally published on The Conversation)

People think they know everything about slavery in the United States, but they don’t. They think the majority of African slaves came to the American colonies, but they didn’t. They talk about 400 hundred years of slavery, but it wasn’t. They claim all Southerners owned slaves, but they didn’t. Some argue it was a long time ago, but it wasn’t.

Slavery has been in the news a lot lately. Perhaps it’s because of the increase in human trafficking on American soil or the headlines about income inequality, the mass incarceration of African Americans or discussions about reparations to the descendants of slaves. Several publications have fueled these conversations: Ta-Nehisi Coates’ The Case for Reparations in The Atlantic Monthly, French economist Thomas Picketty’s Capital in the Twenty First Century, historian Edward Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and The Making of American Capitalism, and law professor Bryan A. Stevenson’s Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption.

As a scholar of slavery at the University of Texas at Austin, I welcome the public debates and connections the American people are making with history. However, there are still many misconceptions about slavery.

I’ve spent my career dispelling myths about “the peculiar institution.” The goal in my courses is not to victimize one group and celebrate another. Instead, we trace the history of slavery in all its forms to make sense of the origins of wealth inequality and the roots of discrimination today. The history of slavery provides deep context to contemporary conversations and counters the distorted facts, internet hoaxes and poor scholarship I caution my students against.

Four myths about slavery

Myth One: The majority of African captives came to what became the United States.

Truth: Only 380,000 or 4-6% came to the United States. The majority of enslaved Africans went to Brazil, followed by the Caribbean. A significant number of enslaved Africans arrived in the American colonies by way of the Caribbean where they were “seasoned” and mentored into slave life. They spent months or years recovering from the harsh realities of the Middle Passage. Once they were forcibly accustomed to slave labor, many were then brought to plantations on American soil.

Myth Two: Slavery lasted for 400 years.

Popular culture is rich with references to 400 years of oppression. There seems to be confusion between the Transatlantic Slave Trade (1440-1888) and the institution of slavery, confusion only reinforced by the Bible, Genesis 15:13:

Then the Lord said to him, ‘Know for certain that for four hundred years your descendants will be strangers in a country not their own and that they will be enslaved and mistreated there.’

Listen to Lupe Fiasco – just one Hip Hop artist to refer to the 400 years – in his 2011 imagining of America without slavery, “All Black Everything”:

[Hook]

You would never know

If you could ever be

If you never try

You would never see

Stayed in Africa

We ain’t never leave

So there were no slaves in our history

Were no slave ships, were no misery, call me crazy, or isn’t he

See I fell asleep and I had a dream, it was all black everything[Verse 1]

Uh, and we ain’t get exploited

White man ain’t feared so he did not destroy it

We ain’t work for free, see they had to employ it

Built it up together so we equally appointed

First 400 years, see we actually enjoyed it

Truth: Slavery was not unique to the United States; it is a part of almost every nation’s history from Greek and Roman civilizations to contemporary forms of human trafficking. The American part of the story lasted fewer than 400 years.

How do we calculate it? Most historians use 1619 as a starting point: 20 Africans referred to as ”servants” arrived in Jamestown, VA on a Dutch ship. It’s important to note, however, that they were not the first Africans on American soil. Africans first arrived in America in the late 16th century not as slaves but as explorers together with Spanish and Portuguese explorers. One of the best known of these African “conquistadors” was Estevancio who traveled throughout the southeast from present day Florida to Texas. As far as the institution of chattel slavery – the treatment of slaves as property – in the United States, if we use 1619 as the beginning and the 1865 Thirteenth Amendment as its end then it lasted 246 years, not 400.

Myth Three: All Southerners owned slaves.

Truth: Roughly 25% of all southerners owned slaves. The fact that one quarter of the Southern population were slaveholders is still shocking to many. This truth brings historical insight to modern conversations about the Occupy Movement, its challenge to the inequality gap and its slogan “we are the 99%.”

Take the case of Texas. When it established statehood, the Lone Star State had a shorter period of Anglo-American chattel slavery than other Southern states – only 1845 to 1865 – because Spain and Mexico had occupied the region for almost one half of the 19th century with policies that either abolished or limited slavery. Still, the number of people impacted by wealth and income inequality is staggering. By 1860, the Texas enslaved population was 182,566, but slaveholders represented 27% of the population, controlled 68% of the government positions and 73% of the wealth. Shocking figures but today’s income gap in Texas is arguably more stark with 10% of tax filers taking home 50% of the income.

Myth Four: Slavery was a long time ago.

Truth: African-Americans have been free in this country for less time than they were enslaved. Do the math: Blacks have been free for 149 years which means that most Americans are two to three generations removed from slavery. However, former slaveholding families have built their legacies on the institution and generated wealth that African-Americans have not been privy to because enslaved labor was forced; segregation maintained wealth disparities; and overt and covert discrimination limited African-American recovery efforts.

The value of slaves

Economists and historians have examined detailed aspects of the enslaved experience for as long as slavery existed. Recent publications related to slavery and capitalism explore economic aspects of cotton production and offer commentary on the amount of wealth generated from enslaved labor.

My own work enters this conversation looking at the value of individual slaves and the ways enslaved people responded to being treated as a commodity. They were bought and sold just like we sell cars and cattle today. They were gifted, deeded and mortgaged the same way we sell houses today. They were itemized and insured the same way we manage our assets and protect our valuables.

Enslaved people were valued at every stage of their lives, from before birth until after death. Slaveholders examined women for their fertility and projected the value of their “future increase.” As they grew up, enslavers assessed their value through a rating system that quantified their work. An “A1 Prime hand” represented one term used for a “first rate” slave who could do the most work in a given day. Their values decreased on a quarter scale from three-fourths hands to one-fourth hands, to a rate of zero, which was typically reserved for elderly or differently abled bondpeople (another term for slaves.)

Guy and Andrew, two prime males sold at the largest auction in US History in 1859, commanded different prices. Although similar in “all marketable points in size, age, and skill,” Guy commanded $1240 while Andrew sold for $1040 because “he had lost his right eye.” A reporter from the New York Tribune noted “that the market value of the right eye in the Southern country is $240.” Enslaved bodies were reduced to monetary values assessed from year to year and sometimes from month to month for their entire lifespan and beyond. By today’s standards, Andrew and Guy would be worth about $33,000-$40,000.

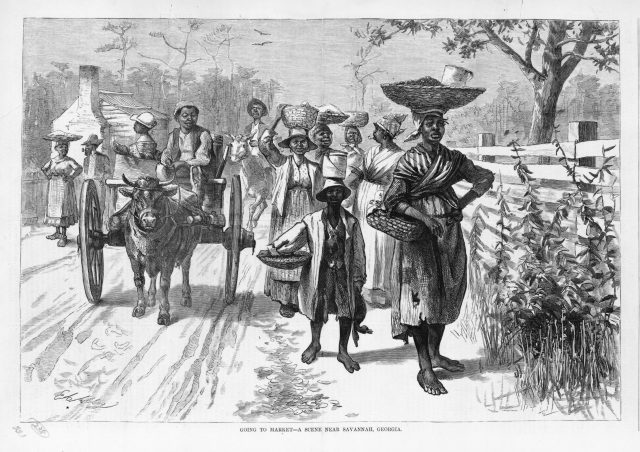

Slavery was an extremely diverse economic institution; one that extrapolated unpaid labor out of people in a variety of settings from small single crop farms and plantations to urban universities. This diversity is also reflected in their prices. Enslaved people understood they were treated as commodities.

“I was sold away from mammy at three years old,” recalled Harriett Hill of Georgia. “I remembers it! It lack selling a calf from the cow,” she shared in a 1930s interview with the Works Progress Administration. “We are human beings” she told her interviewer. Those in bondage understood their status. Even though Harriet Hill “was too little to remember her price when she was three, she recalled being sold for $1400 at age 9 or 10, “I never could forget it.”

Slavery in popular culture

Slavery is part and parcel of American popular culture but for more than 30 years the television mini-series Roots was the primary visual representation of the institution except for a handful of independent (and not widely known) films such as Haile Gerima’s Sankofa or the Brazilian Quilombo. Today Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave is a box office success, actress Azia Mira Dungey has a popular web series called Ask a Slave, and in Cash Crop sculptor Stephen Hayes compares the slave ships of the 18th century with third world sweatshops.

From the serious – PBS’s award-winning Many Rivers to Cross – and the interactive Slave Dwelling Project- whereby school aged children spend the night in slave cabins – to the comic at Saturday Night Live, slavery is today front and center.

The elephant that sits at the center of our history is coming into focus. American slavery happened — we are still living with its consequences.

Daina Ramey Berry receives funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and is a Public Voices Fellow with The Op-Ed Project.

Further reading:

Articles about slavery on Not Even Past

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

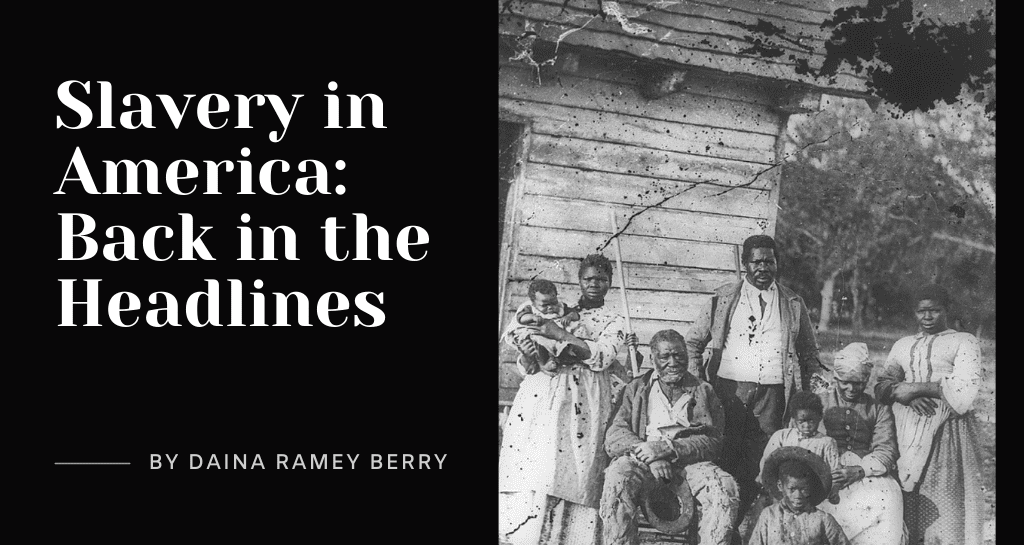

Image credit – O’Sullivan, Timothy H, photographer. Five generations on Smith’s Plantation, Beaufort, South Carolina. Beaufort South Carolina, 1862. [, Printed Later] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/98504449/.