Modern Fossils: What Objects Tell Us About the Anthropocene / David Rooney

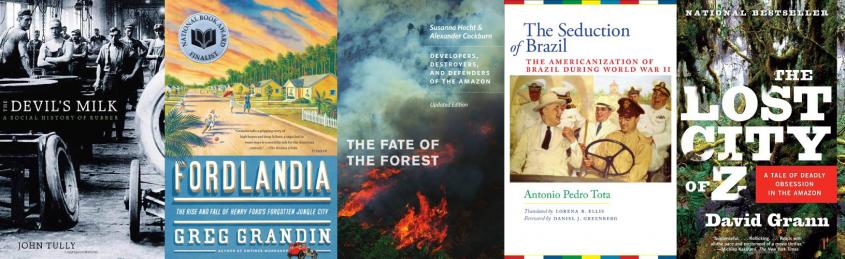

Future Remains is a collection of essays that explore how objects might narrate increasing human dominance over the environment and the lessons we can glean from that shift in perspective. What would a museum of the present look like? What items and memories of our current epoch would make the cut, representing this time of climate change and rapid technological leaps for a future historian? Future Remains attempts to answer these questions, cataloging a series of objects curated by an “Anthropocene Slam” that invited artists and scholars to give a ten-minute pitch defending their item as representative of the Anthropocene.

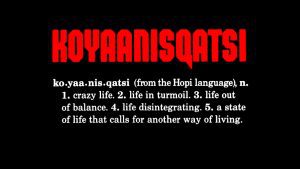

“Anthropocene,” from Anthropos (man) and cene (recent), is a term put forth by earth scientists Eugene Stoermer and Paul Crutzen to designate a new geological epoch defined by the unprecedented effect of humanity as a geological agent. The Anthropocene frame has been taken up by a variety of scholars, activists, and techno-optimists in a surge of interdisciplinary scholarship and policy advocacy. Fifteen objects made the cut, playfully entitled a “Cabinet of Curiosities.” The items ranged from the feathers of a goose destroyed by the impact of a jet engine to a jar of layered North Carolina beach sand and a recording of a Māori re-creation of an extinct bird call. Some essays, like Laura Pulido’s on climate and racial sacrifice, offer a broader theoretical perspective on Anthropocene, but the bulk of the works attempt to make sense of the Anthropocene through a specific item selected from the cabinet. Future Remains is divided into four thematic sections, each revealing core aspects of the Anthropocene and charting divergent futures: an anthropocentric acceleration of modernization to geo-engineer nature or a self-reflective, ethically driven “slowing down” of human exceptionalism.

The first section, Hubris, catalogs a set of beliefs about how we might turn the universalism of the Anthropocene in humanity’s favor. Thomas Matz and Nicole Heller’s essay on the history of a jar of North Carolina sand carefully teases out both the futility of geo-engineering beaches and the interests of capital that decide these actions for the many. Examining concrete and the pesticide pump, other essays in this section reveal how little knowledge most observers truly have about the seemingly banal (concrete mixing) or the ecological (the effect of pesticides). Joseph Masco’s chapter on the use of nuclear explosions to exploit the environment is an eye-opening criticism of the hubris of those who believe humanity must become “good gods” to ride out the Anthropocene. Gregg Mitman pleads for readers to not leave the Anthropocene to the seemingly objective analysis of chemistry and geology. Instead, the Anthropocene must become a site of social contestation to establish equitable futures.

The second section deals with life and death in the Anthropocene. Gary Kroll, borrowing heavily from Donna Haraway’s When Species Meet, remarks that death cannot be avoided in the Anthropocene. His essay examines the remains of a goose that collided with an airplane’s turbine engine and forced an emergency landing, what became known as the “Miracle on the Hudson.” Plane-animal collisions have become so common that the term “snarge” was coined to describe the remains of animals killed from human transportation systems. For Kroll, all forms of life (especially geological actors like humans) participate in some form of killing as a result of our inevitable entanglement with other beings. The inclusion of a feather from the goose killed by a jet engine asks observers to ponder how to become more thoughtful and concerned with how industrialized lifestyles produce murders. In this vein, Pulido situates the Anthropocene as a racial world-order, where predominantly white countries are unconcerned with the environmental devastation and premature deaths they hoist onto “darker nations,” a criticism reflected in Julianne Lutz Warren’s description of colonial violence in New Zealand.

The third section focuses on labor. A monkey wrench reminds us of the physical work required to power the industrial machines that pollute the globe, while a Quaker quilt ties together slavery, complicity in violence, and the limits of human agency. The concluding theme, “making,” connects the forms of self-reflection inspired by the Anthropocene, including literal self-reflection in a mirror. Tying these works together, Robert Emmett describes Jared Farmer’s discussion of e-waste in connection to the power of art, re-working the Anthropocene in a more “beautiful” way. The physical objects examined concretize this argument, reflecting the social worlds and emotive connections that inform environmental perspectives.

The book covers a variety of perspectives from different authors, often in agreement but sometimes in explicit contrast with one another. At times this makes for a jarring read. However, this can also be considered a strength. By crossing traditional disciplinary boundaries, the combination of different perspectives unsettles any easy account of our current epoch. Indeed, the function of these objects is not simply to paint an accurate tale of the Anthropocene and its core actors in a way that might satisfy future curiosity. Rather, the power of these objects is that they are curious and strange: they provoke stories and “structures of feelings” that inspire readers to relate differently to the environment and to each other. I would recommend this accessible book to historians, social theorists, and anyone interested in critical scholarship on class or race and the debates over how to situate these within environmental history.

David Rooney is a graduate student in Communication Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

Anthropocene: Reshaping the Past to Remake the Future / Felipe Vilo Muñoz

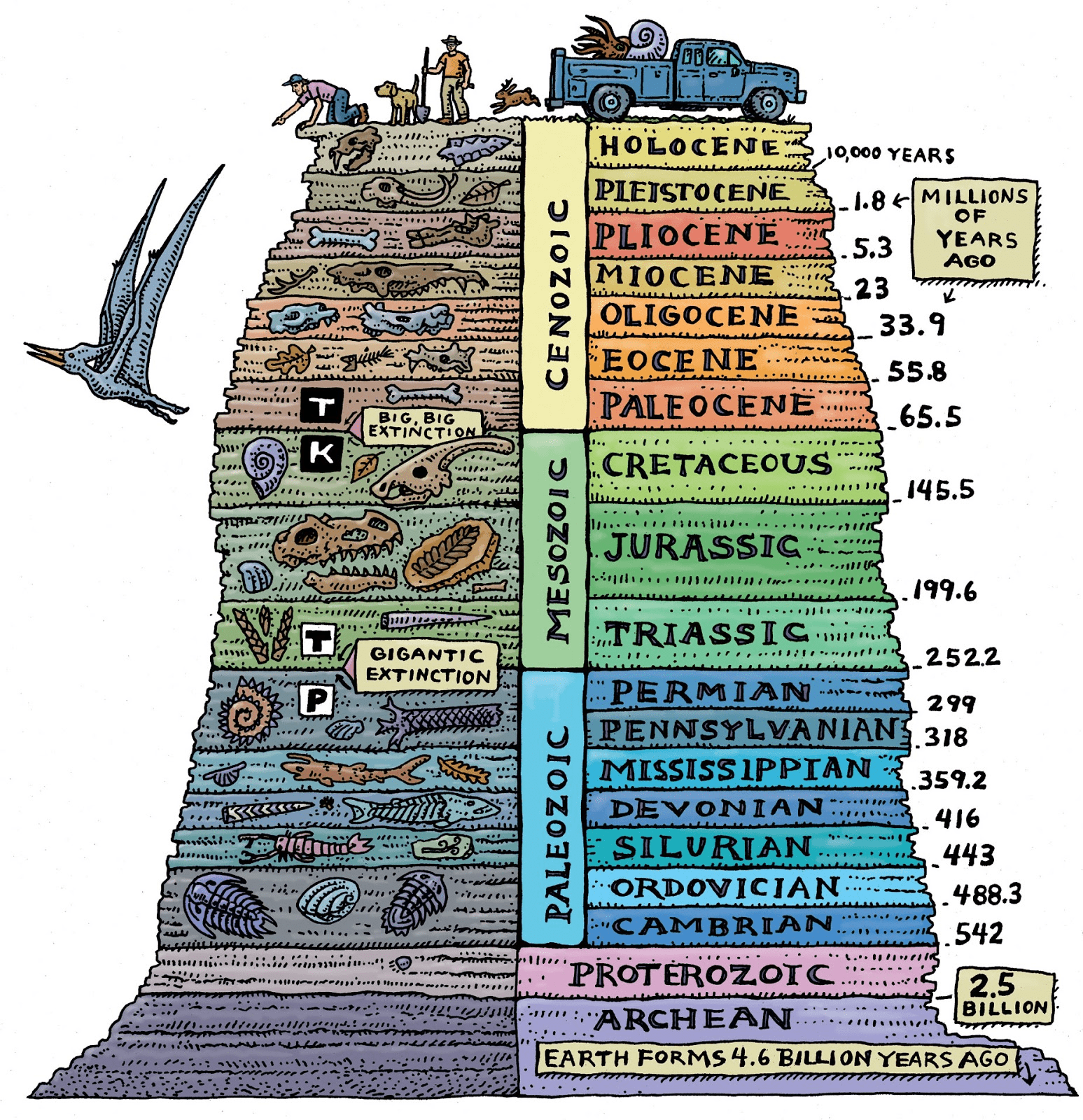

A decade ago, I used to go on excursions with my physical geography class. I learned how to recognize different geological periods by examining a hillside terrain’s colors on those trips. One gets an idea of the vast geomorphologic cycles that have shaped the Earth for millions of years by looking at the terrain. Our current existence will become yet another layer of sediment in future strata. For many of us, epochs such as the Miocene or Holocene are little more than a name, but we might start to think about what kind of color our current time will be painted. Will it be a brighter color? Or might it be another murkier layer in our planet’s history?

Stretching the past to recognize our mark on an unwritten future is at the core of the notion of the Anthropocene. This period acknowledges that our species has started to modify the planet as a new dominant geological force. What were the origins of our impact on the earth? And what might our remains mean to historians of the future? Future Remains addresses these questions. In it, twenty-one authors propose fifteen different material objects that could become part of a global natural history museum––a cabinet of curiosities for a future we might not witness. For the moment, we can reflect on this temporality-in-the-making. “The Anthropocene,” Rob Nixon writes in the first chapter, “thus pulls us simultaneously into deep pasts and deep futures that are unfamiliar, uncomfortable terrain for historiography” (5).

Identifying when people started to change nature is not easy. However, the firsts chapters specify some elements that give us a glimpse of how many changes human intervention has brought to our planet. Some chapters center on the past century, such as Joseph Masco’s “Project Plowshare,” a promotional film that explained plans to use nuclear explosions as a geoengineering tool for construction and mineral extraction. This plan never became a reality, but it gives us the first glimpse of our role in taming nature. Another chapter considers a deeper past. In “Anthropocene in a Jar,” Tomas Matza and Nicole Heller detail the historical reconstruction of the Wrightsville beach in North Carolina and its different sediments collected in a kimchi jar. This pot contains different colors and stripes that reflect different periods of the beach’s history. The stripes also show the effects of beach “nourishment”–– the practice of importing sand that has reshaped the coastline since the first decades of the twentieth century. Similarly, the chapter “Concretes Speak: A Play in One Act” addresses this material’s connection to humans, from the footprints of ancient cultures of 6500 BCE to our modern skyscrapers. These three examples reflect an initial step toward understanding the new dynamics of our “hubristic presence” on this planet. Nevertheless, the most significant human impact has occurred in recent centuries with the onset of global warming. For historians of the Anthropocene, this is a breaking point in our planet’s history.

As sea levels and temperatures rise, provoking fires and deforestation, the Anthropocene has reshaped natural conditions. We are left with hard choices to sustain our presence with the rest of planet life forms. Gregg Mitman’s chapter adds to the Anthropocene debate, arguing for a relational approach with the living forms that coexist with us. Here, the vision of the “good Anthropocene” in which technoscience will provide innovative tools to regulate our impact on nature intertwines with the possibility of a dystopic future in which we might follow the fate of other extinct species.

The entanglement of those two positions appears in Josh Woda’s “Artificial Coral Reef,” Nils Hanwahr’s “Marine Animal Satellite Tags,” and Elizabeth Hennessy’s “Cryogenic freezer box.” Together these give us a taste of this imminent future. Here, the fabrication of material devices sustains our combination of demanding resources alongside the regulation of natural habitats. This applies even more so for Hennessy’s chapter which reflects of using cryogenic technologies to bring back extinct species.

Other chapters recognize how our actions impact the lives of non-humans. Gary Kroll’s “Snarge” chapter questions the normalization of animal killing and the destruction of habitats. Julianne Lutz Warren’s chapter, “Huia Echoes,” captivates the reader with recordings of a Maori voice attempting to reconstruct the sounds of an extinct bird. In these examples, we understand the menace that our species presents to endangered life forms. Nevertheless, the history of those extinct or endangered species reminds us that we could share the same misfortune.

Other essays address how the Anthropocene can also make us rethink our present. In “The Mirror— Testing the Counter-Anthropocene,” Sverker Sörlin questions whether this ecological imbalance is a problem of our current time. He considers that our present can find other answers that could reshape how we construct the Anthropocene. As a result, Sörlin present us how Anthropocene hasn’t determined our fate, on contrary humanity is constantly writing its own present. Thus, the author endorses an “Anthropocene of hope”, which is continually evolving with us from the permanent actions we create about the planet.

In this way, Anthropocene historiography creates a mosaic view in which different images make us think about divergent possibilities for our species. Our actions will continue to reshape the Anthropocene, forever remaking our cabinet of curiosities. The only thing that remains clear is that this new period has given us the responsibility to start writing history. In doing so, we will give color to the sediments that we leave to our descendants in the eons to come. Thus, Future Remains should be reading as an invitation to rethink our responsibility in our historical footprint making. A task that we are still struggling to accept to its full extend.

Felipe Vilo Muñoz is a graduate student in the History Department at the University of Texas at Austin.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.