By More than Providence: Grand Strategy and American Power in the Asia Pacific Since 1783. By Michael J. Green. Illustrated. 725 pp. Columbia University Press. $45.

by Jonathan R. Hunt

University of Southhampton

First Published by The Imperial and Global Forum (October 23, 2017).

Otto von Bismarck once remarked that the United States was blessed: “The Americans are truly a lucky people. They are bordered to the north and south by weak neighbours and to the east and west by fish.” Thanks to this geographic grace, George Washington could call for freedom from “entangling alliances” in his farewell address. This distance has also bred a strong undercurrent of parochialism and chauvinism in American culture. From these two impulses has emerged the conceptual DNA of American foreign relations in the form of two dichotomies—exemplarism versus interventionism; cosmopolitanism versus exceptionalism—lending form and structure to debates about how a democratic people should manage their affairs in an often unkind, even hostile, world.

Otto von Bismarck once remarked that the United States was blessed: “The Americans are truly a lucky people. They are bordered to the north and south by weak neighbours and to the east and west by fish.” Thanks to this geographic grace, George Washington could call for freedom from “entangling alliances” in his farewell address. This distance has also bred a strong undercurrent of parochialism and chauvinism in American culture. From these two impulses has emerged the conceptual DNA of American foreign relations in the form of two dichotomies—exemplarism versus interventionism; cosmopolitanism versus exceptionalism—lending form and structure to debates about how a democratic people should manage their affairs in an often unkind, even hostile, world.

In his sweeping and authoritative account of United States grand strategy in the Asia Pacific, Michael J. Green reminds us that Americans have long regarded this maritime expanse – from the Aleutians to Cape Horn in the Western Hemisphere across to Australasia and Sakhalin in the Eastern — as integral to defending their ‘empire of liberty’. Nineteenth-century policymakers from Thomas Jefferson and Matthew C. Perry to Henry Seward and John Hay sought to pry open these watery frontiers to American influence (and conquest) so as to stave off any threats that might overleap the Pacific Ocean. Their twentieth-century successors, Alfred Thayer Mahan and Teddy Roosevelt, George Marshall and Franklin Roosevelt, Dean Acheson and Harry Truman, Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon, George Shultz and Ronald Reagan, Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, among others, have fought to keep the Pacific an American lake – for now.

Green brings scholarly and policymaking credentials to this tour d’horizon. Japan Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C., and an associate professor at Georgetown University (not to mention the Asia hand in George W. Bush’s White House), he is supremely qualified to narrate and appraise more than two centuries of decisions, processes, and events. On a hemispheric tableau teeming with squadrons, legations, missionaries, gunboats, marines, emissaries, island chains, and good intentions, he paints a United States government in pursuit of a “distinct strategic approach” that would guarantee “that the Pacific Ocean remain[ed] a conduit for American ideas and goods to flow westward, and not for threats to flow eastward toward the homeland.” (5)

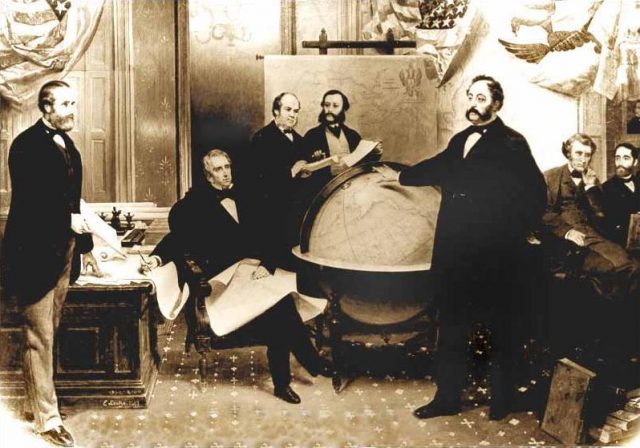

The Alaska Purchase, 1867. Left to Right: Robert S. Chew, Secretary of State (USA); William H. Seward; William Hunter; Mr. Bodisco, Russian Ambassador; Baron de Stoeckl, Charles Sumner; Fredrick W. Seward (via Wikimedia Commons)

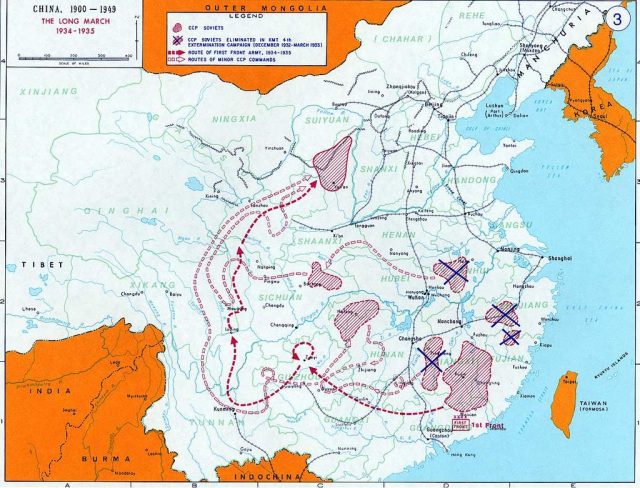

Green charts this strategic disposition from the Articles of Confederation to Obama’s pivot to Asia, dividing the chronology into four eras when a rising power—the United States, Japan, the Soviet Union, and China—convulsed the region’s politics. American assertiveness waxed as European empires toggled from New World outposts to Asian colonialism in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century. In short order, Jefferson’s greater Louisiana brought on James Monroe’s enunciation of an American protectorate in its hemisphere, John Tyler’s extension of that Monroe Doctrine to the Sandwich Islands (Hawai’i to natives Polynesians), and William Seward’s purchase of Alaska (dubbed his ‘ice box’), before the Civil War cut short the Pacific ambitions of Lincoln’s secretary of state.

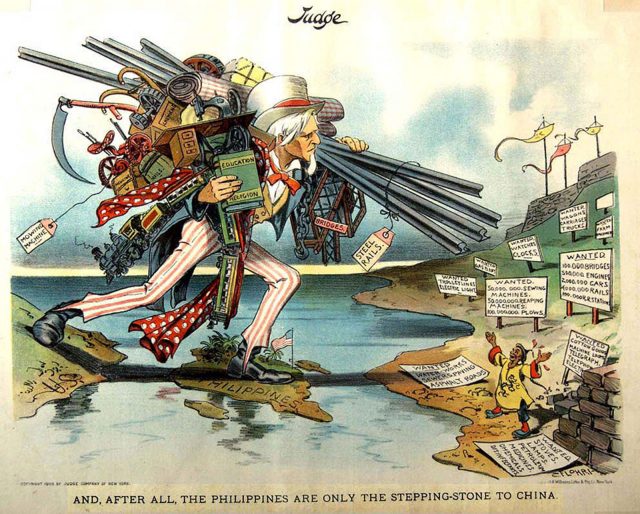

This section is rich in geography and personality, acquainting readers with a century-long campaign to seize “stepping stones,” most pivotally Hawai’i, in the Pacific, introducing swashbucklers like Captain David Porter, whose piratical voyage to the Pacific in the War of 1812 foreshadowed the fusion of mercenary and military aims that would become the country’s modus operandi, and keeping a running tally of plenipotentiaries (of uneven quality) who served in an ever more prostrate Qing China. Green’s treatment of dusty concordats such as the 1858 Treaty of Tientsin, in which the United States pledged its “good offices” to Beijing in dealings with rapacious British, French, and Russians after the second Opium War, and the 1868 Burlingame Treaty, which recognized Chinese eminent domain over its whole territory, is welcome. He is sharp on the strategic contours of these many-sided rivalries; yet, while alive to the noxious influence of Anglo-Saxonism in nineteenth-century American culture, his tendency to treat republican virtues as more significant in U.S. foreign policy than Manifest Destiny chauvinism yields a handful of errors and omissions.

Green’s heroes are, above all, republican realists, high priests at the altar of the balance of power who still find ways to promote democracy, the rule of law, and free trade in the wider world. Thus, his hinge is fin-de-siècle power couple are Theodore Roosevelt and Alfred Thayer Mahan—the quintessential man of action married to the man of ideas. The latter expounded a strategic theory based on naval bases, sea lanes, and deep-water armadas; the former built a Great White Fleet to enforce it. The tendency to view America’s holdings in the Pacific, mostly insular takings such as Guam, Hawai’i, and the Philippines, as incidental rather than intrinsic to American power leads Green to paint the Bull Moose in overly Mahanian hues, emphasizing his naval leadership and power-balancing after the 1905 Russo-Japanese war while downplaying his protectionism and colonialism. What passed for strategic élan in Washington, after all, in Manila simply looked like another instance of imperialism. He is on firmer grounds in his treatment of John Hay’s push for trade reciprocity in China, contesting Wisconsin School members who deem the Open Notes clear evidence that the United States was (and remains) a capitalist octopus in ravenous search of pliant markets.

“AND, AFTER ALL, THE PHILIPPINES ARE ONLY THE STEPPING-STONE TO CHINA” – cartoon from Judge Magazine showing Uncle Sam with the “tools of modern civilization” using the Philippines as a stepping stone to China, ca. early 1900s (via Wikimedia Commons)

His appraisal of Asia policy from Teddy Roosevelt to cousin Franklin is scathing, and for good reason. Wilson sold out Korea and China’s Shangdong province to Japan for his League of Nations, before Calvin Coolidge, Warren Harding, and Herbert Hoover retracted U.S. power after Teddy’s ally, Henry Cabot Lodge, nixed an American role in the league. Green includes a revealing vignette about American interwar finance, as William Straight and J. P. Morgan sought Chinese debt before the crash of October 24, 1929, put paid to their schemes. For Green, the Department of State’s willingness to accommodate Japan, whose militaristic expansions would upset the (perhaps excessively) elegant Washington Treaty, violated Mahan’s signature insight—playing sides against one another to avert a peer regional competitor from arising. Although the Japanese Co-Prosperity Sphere bore this warning out, he dismisses too perfunctorily the alternatives that Franklin Roosevelt’s Asianists—Lawrence A. Lowell, Joseph Grew, Stanley Hornbeck, and John Von Antwerp MacMurray—put forth. After all, MacMurray’s call to retrench at the Second Island Chain prefigured modern realists like Barry Posen, whose 2014 Restraint contends that the United States would best observe Mahan’s dictum by re-drawing its defense lines further west while retaining command of the commons. (To be fair, assured nuclear retaliation has now nullified whatever existential threats had existed.)

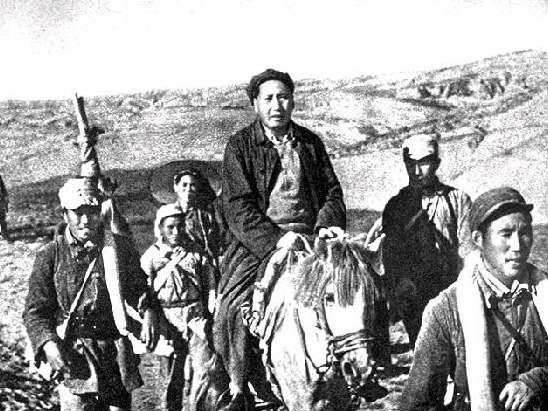

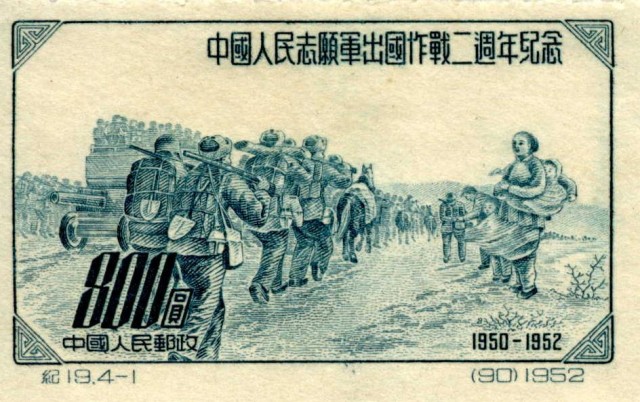

What happened after the United States sanctioned Japan for yet another massacre in China in 1940, after seven years of turning a blind eye (par for the course in the Guernica decade), was the country’s first fair fight in the Pacific. Green is too credulous that Hiroshima and Nagasaki won the war (Tsuyoshi Hasegawa shows that the Soviet declaration of war was equally if not more decisive), but his verdict that Roosevelt and Truman failed to leverage Chester Nimitz and Douglas MacArthur’s military triumphs on behalf of a grand strategy that would deliver post-war security is devastating. When the Soviet Union switched from wartime ally to geo-ideological adversary, U.S. officials overlooked the Kuomingtang’s weakness and Mao Tse-Tung’s zeal; as a result, they held out on China serving as a fourth United Nations policeman. This even as Chiang Kai-Shek’s battle lines crumbled, in part for lack of American support (apart from a woefully inadequate 900 military advisors), leading to the loss of China and setting in train a series of events that would culminate in the militarization of containment in Korea and the Americanization of the war for peace in Vietnam.

The Cold War tested American grand strategy in ways new and old, first with proxy wars fused to anticolonial struggles, and then the Soviet Union’s massive naval build-up in the 1980s. Next to old chestnuts such as the extent of continuity in personnel and policy between the Kennedy and Johnson administrations is the conspicuous omission of the former’s obsession with China’s nuclear-weapons program (its first nuclear test was on October 16, 1964); even though it was nearly a decade before Beijing fielded a survivable arsenal, the first Asian nuclear-weapon state was a game-changer, catalysing the Vietnam War, severely constraining U.S. military options once there, and helping usher the People’s Republic into the United Nations. Likewise, there is a clear and disturbing hierarchy of liberal values for Green, with genocide ranking far lower than free trade. When he supports the contention that “noble cause” advocates make that the war helped cauterize communist insurgencies in Indochina, Malaysia, and Thailand, for instance, he glosses over the 500,000 Indonesians estimated dead in the mass killings that shepherded the Suharto dictatorship into power in Jakarta.

Nixon shakes hands with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai. It was the first trip made by an American president to the nation, 1972 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Nixon earns plaudits as an unsentimental president who ended twenty-five years of non-recognition between the most powerful and most populous nations on Earth; but Reagan, who convinced Japan to serve as an “unsinkable aircraft carrier,” (405) invested massively in the U.S. Navy, and midwifed democracy movements in the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan, receives the lion’s share of praise. In Green’s telling, his emphasis on security and stability afforded strongmen like Ferdinand Marcos and Park Chung-hee the leeway to sanction free elections. Reagan’s application of military, ministerial, and moral instruments to a coherent strategy in the region affords a case study for wedding power to principle effectively. Green also holds it to offer lessons for the newest and most challenging contender for regional pre-eminence: The People’s Republic China.

The final section dovetails with a set of vigorous debates now gripping Washington and Asian capitals. Can the United States and China resolve differences without military recourse as Beijing stakes its position in the South China Sea and Senkaku islands? Will America’s hubs-and-spoke network of alliances survive as China’s wealth and power cast a spell over neutrals and allies alike? Can Washington nudge the alphabet soup of multilateral institutions toward trans-oceanic rather than intra-regional orientations, especially now that the Trans-Pacific Partnership is comatose? Will the U.S. join the Beijing-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank or acquiesce to the PRC’s “One Belt One Road” initiative of ports, highways, railways, and pipelines? Will Washington and its partners succeed in embedding Beijing as a stakeholder in the global rules-based order or will it shear off its sphere of influence from the norms and institutions that expedited its return to greatness?

Bill Clinton garners high marks for his strategy of engaging and balancing China, a two-pronged approach that George W. Bush and Barack Obama would adopt. And while Donald Trump’s beleaguered and inept administration has so far proven less unorthodox than anticipated on trade, Green’s emphasis on island chains, aircrafts carriers, and strategic sea-lift when compared to human rights, labour, immigration, and cultural dialogue yields a deafening silence on the centrifugal forces now eviscerating what once passed as bipartisan consensus on the importance of engagement in the Asia-Pacific for the security and prosperity of the United States.

Also by Jonathan Hunt on Not Even Past:

1986 Reykjavík Summit between Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev

Iran’s Nuclear Program and the History of the IAEA

Review: The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and its Dangerous Legacy

You may also like:

Foreign Policy from Candidate to President: Richard Nixon and the Lesson of Biafra by Roy Doron

CIA Study: “Consequences to the US of Communist Domination of Mainland Southeast Asia,” October 13, 1950 by Mark A. Lawrence

David A. Conrad reviews Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II