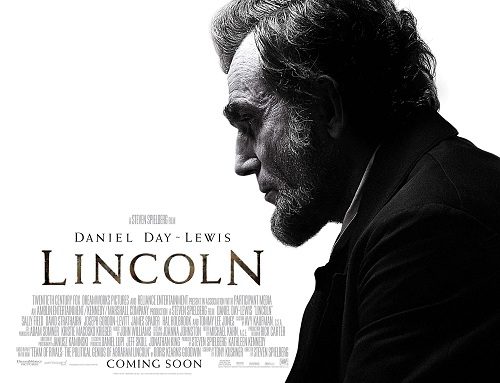

The monument at Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historical Park (via Wikimedia Commons)

by Jesse Ritner

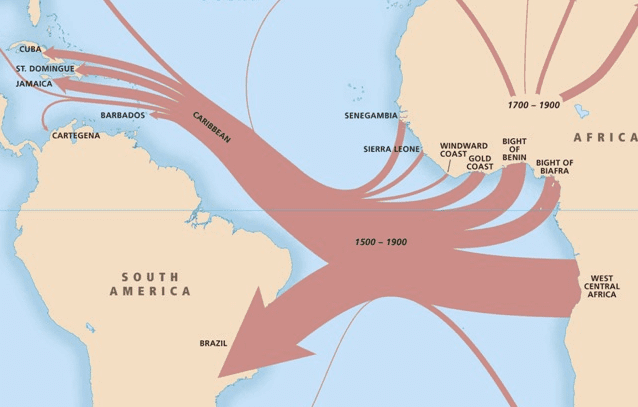

School children across the United States learn that Abraham Lincoln was born in a log cabin. For seven weeks this past summer I worked at the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historical Park in Hodgenville, Kentucky, where that cabin (as legend has it) is encased in a stone monument. Imposingly large when viewed from the bottom of its 56 steps, the monument is almost claustrophobic inside. Designed by John Russel Pope, the early twentieth-century’s titan of neo-classical monuments and government buildings, the monument only has one room, about the size of a large living-room. The entire log cabin fits inside, reinforcing the difference between the monument built in Lincoln’s honor and his humble origins. The Grecian inspired edifice was built between 1909 and 1911, atop the knoll where legend (and some deeds with Thomas Lincoln’s name) lead us to believe Abraham Lincoln was born. The now largely forgotten monument was once national news. Over 100,000 Americans donated money to build the publicly funded temple. The cornerstone was laid by none other than President Theodore Roosevelt and, two years later, it was dedicated by President William Howard Taft, himself a member of the Lincoln Farm Association, which led the fundraising effort.

The intended lesson of the Lincoln Birthplace Memorial is clear. Those who begin in rags, can rise to riches. Those men who save the nation will, for their services, have their less than impressive childhood homes enshrined in granite and neo-classical architecture, thereby tying them for eternity to the everlasting fight for freedom and democracy that can be traced all the way from ancient Athens to today’s rolling hills of Kentucky. Yet, the monument and the cabin inside teach us much more than an overwrought story about the American dream; instead, it serves as a piece of history in of itself.

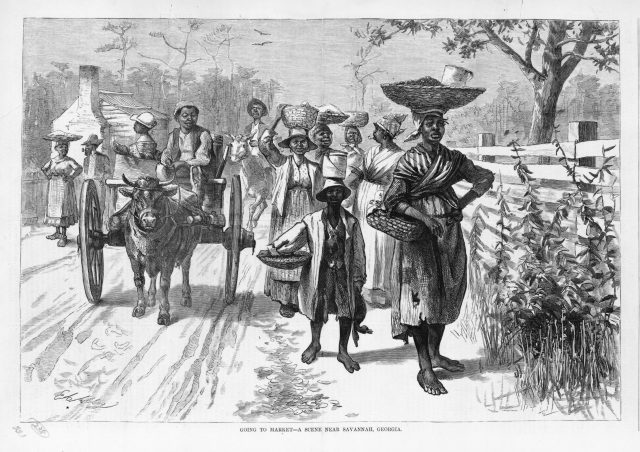

The cabin inside the monument’s granite walls never housed the Lincoln family. It was constructed in 1895 by entrepreneur Alfred Dennett and his agent, James Bigham, from logs found in a log cabin near the sinking spring where records suggest Lincoln was born. In 1897, the fabricated cabin was toured around the country, where it was matched with another ersatz birthplace cabin – that of none other than Confederate President Jefferson Davis. As the caravan of cabins continued around the United States, it finally landed on Coney Island. There, due to poor organization while shipping, parts of each cabin became mixed so they were simply joined together creating a single Lincoln-Davis Birthplace Cabin. According to James W. Loewen, author of Lies across America, when this cabin, now combining logs from the separate counterfeit cabins of the enemies of the Civil War, was sent back to Kentucky in 1906, it was represented as Lincoln’s “original” birthplace cabin. While the National Park Service does acknowledge that the cabin is not the original, but instead is “symbolic” (the quotation marks are theirs, not mine), it is largely silent on the actual origins of the cabin.

The symbolic cabin enshrined in the monument at the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historical Park (via Wikimedia Commons)

In today’s conversations about Confederate statues, few are discussing the relationship between Confederate and Union memorials dating from the early twentieth century, both of which quite consciously use matching metaphors to affect their viewers. In Kentucky, monuments such as Lincoln’s birthplace offer insight into the way historical narratives created by turn of the century endeavors in public history by both Union and Confederate supporters are often intertwined, despite the heated rhetoric and violence that results from these supposedly competing historical narratives today.

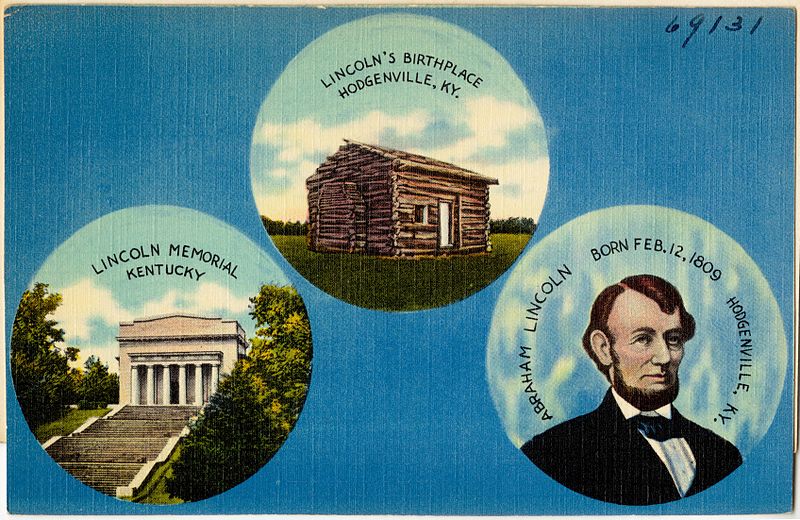

The Park Service’s silence calls to question why we need the monument in the first place and why we, as taxpayers, should support its preservation. As a remembrance of President Lincoln, the monument and park are markedly outdated. Far removed from population centers, the monument is largely forgotten. On the other hand, the story of the cabin now enshrined in its “Temple of Fame,” as Theodore Roosevelt dubbed the granite structure, gives real insight into the way Americans, both Confederate sympathizers and Union patriots, collectively built historical narratives about the Civil War in the late nineteenth century. Both Presidents Davis and Lincoln were born in Kentucky and, at the turn of the century, their rags to riches stories were not seen as inherently independent of each other, but were instead part of a single American narrative that both Southerners and Northerners could claim as their birthright.

A postcard of Lincoln’s Birthplace Memorial, ca. 1930-1945 (via Boston Public Library)

The cabin today, with no mention of the monument’s convoluted history, ignores the partially fabricated histories that brought both to power, and brought these Kentucky brothers symbolically back together, even after a long, violent, and devastating war. But, the monument, despite the faults inherent in its creation, also holds valuable potential as a piece of public history that can truly engage with the way in which historical narratives are created and why monuments are built, rather than simply reinforcing centuries old attempts at public education and nation building. It suggests historical precedents to the Republican Party simultaneously claiming heritage as the party of Lincoln, while supporting the maintenance of Confederate monuments and minimizing or even erasing the history of slavery and its role in the bloody Civil War. And it shows that in towns like Hodgenville, where Confederate flags fly freely next to memorials to Lincoln, the apparent conflict in historical memory is not new, but is part of a conscious narrative built in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War and continuing today.

The current dialog revolving around Confederate memorials is far more complicated than many analyses acknowledge. Considering the current unrest regarding Civil War monuments, it is necessary for us to examine the influence of all sides on the historical narratives they choose to create. Remedying the wrongs that statues of people such as Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee represent is harder than simply taking prominent statues down. As a nation we must reassess the way we have remembered the entire history of the Civil War and we must reexamine the ways past generations remembered as well, regardless of whether the historical figures in question are currently viewed as villains or heroes.

You may also like:

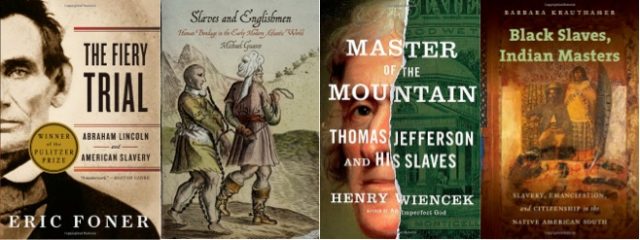

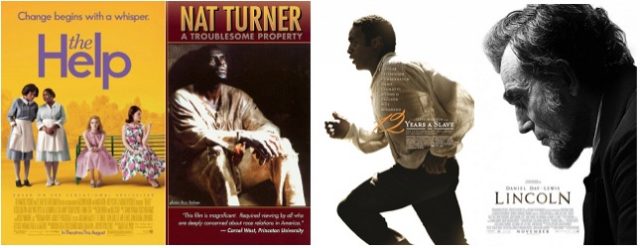

A Historian views Spielberg’s Lincoln (2012), by Nicholas Roland

Watch: panel discussion of confederate statues at the University of Texas

Charley Binkow on the Lincoln Archives Digital Project