by Jeremi Suri

“I judge that it might be true that fortune is arbiter of half of our actions, but also that she leaves the other half, or close to it, for us to govern. And I liken her to one of these violent rivers which, when they become enraged, flood the plains, ruin the trees and the buildings, lift earth from this part, drop in another; each person flees before them, everyone yields to their impetus without being able to hinder them in any regard. And although they are like this, it is not as if men, when times are quiet, could not provide them with dikes and dams so that when they rise later, either they go by a canal or their impetus is neither so wanton nor so damaging.”

“I judge that it might be true that fortune is arbiter of half of our actions, but also that she leaves the other half, or close to it, for us to govern. And I liken her to one of these violent rivers which, when they become enraged, flood the plains, ruin the trees and the buildings, lift earth from this part, drop in another; each person flees before them, everyone yields to their impetus without being able to hinder them in any regard. And although they are like this, it is not as if men, when times are quiet, could not provide them with dikes and dams so that when they rise later, either they go by a canal or their impetus is neither so wanton nor so damaging.”

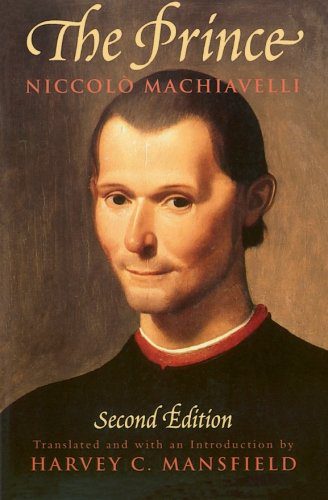

Machiavelli offers many kinds of advice to the modern prince: manipulate fear, spread benefits among the population, seek broad counsel, and take strategic risks. He envisions a strong and wise leader who protects the interests and freedoms of his people. Machiavelli also hopes that the modern prince will employ ambitious, experienced, and intellectual advisers, like himself.

For historians and our students, there are also many valuable passages in Machiavelli. Among them, Machiavelli’s reflections on the struggle between fortune and will – what historians often call “structure” and “agency” – are particularly worthwhile. The Florentine thinker describes the historical tectonics that even the most powerful figure cannot resist: shifts in military capabilities, economic advantages, and basic human demography. These historical tectonics are not deterministic, but they are too powerful and too dependent on past actions for anyone to change them in the short term. The prince must understand context and adjust. This is basic historical humility.

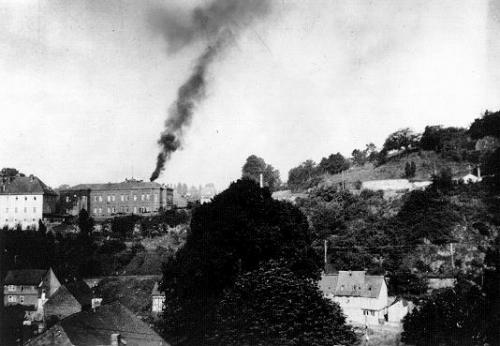

1558 fresco depicting the 1529-30 Siege of Florence (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Machiavelli combines this humility with a clever recovery for greatness in human agency. Amidst the historical tectonics of any time, there are spaces where choices can have a huge effect. Machiavelli’s Florence could not turn back the rise of French military and economic power, but it could reorganize itself and nurture qualities (“virtues”) to prepare for the actions of the powerful monarchy in the north. Leadership, for Machiavelli, came from studying the historical tectonics, anticipating what they would mean for the future, and identifying choices that could improve preparation. He knew that sixteenth-century Florence’s strategic options were limited, but he also saw ways that the leaders of the city-state could maximize benefits and limit suffering with forward-looking decisions. To look forward, however, meant understanding how the future would likely emerge from the trajectory of change starting in the past.

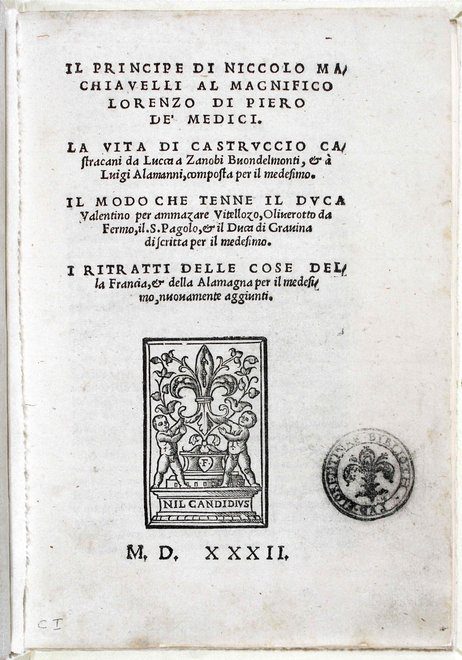

1532 Florentine edition of The Prince (Image courtesy of NPR/Donato Pineider)

We study history, among other reasons, because it helps us as citizens to understand the forces that shape our lives and identify how we can make a difference. Every successful person that I have met, in any field of endeavor, has reflected on what Machiavelli called the fundamental struggle between fortune and will. It is unresolvable. It is not susceptible to mathematical formulas, simple principles, or glib models. It is a timeless struggle, but it is different with every person and in every moment. We study history so we can decide for ourselves how we see our place and purpose in a historical continuum that rushes before our eyes, where we are hoping, at best, to catch a good wave.

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines

**

You may also like:

Alison Frazier evaluating some “Lightly Fictionalized” books about the Italian Renaissance

And Ben Breen revealing the importance of clothing the Renaissance era

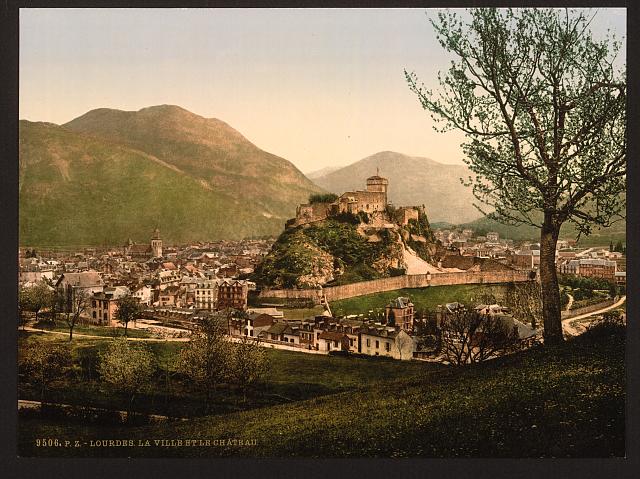

The Spanish Pyrenees, 2009 (Image courtesy of User Miguel303xm/Wikimedia Commons)

The Spanish Pyrenees, 2009 (Image courtesy of User Miguel303xm/Wikimedia Commons) The French Pyrenees, 2010 (Image courtesy of Nicolas guionnet/Wikimedia Commons)

The French Pyrenees, 2010 (Image courtesy of Nicolas guionnet/Wikimedia Commons)