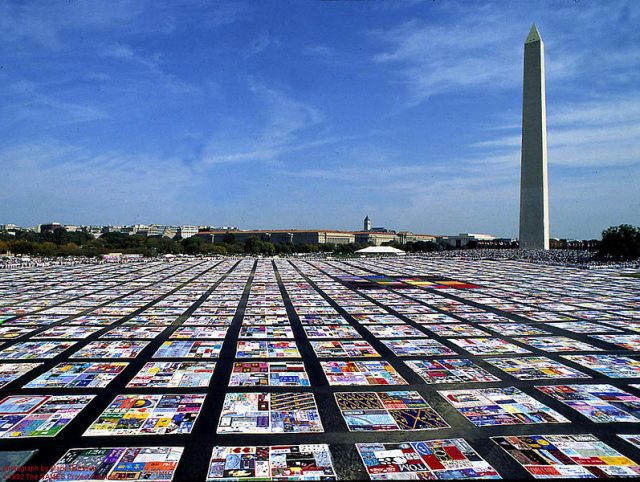

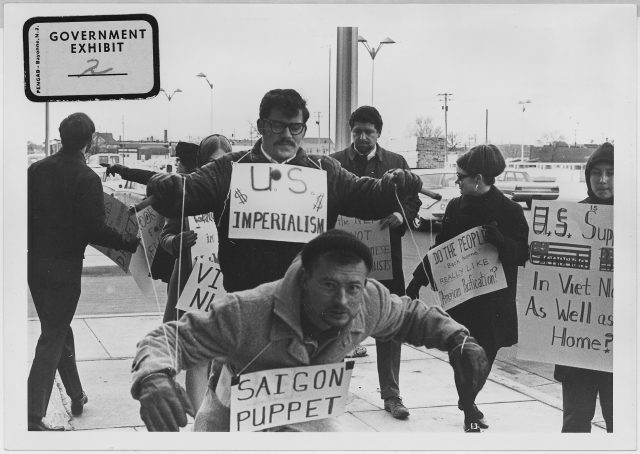

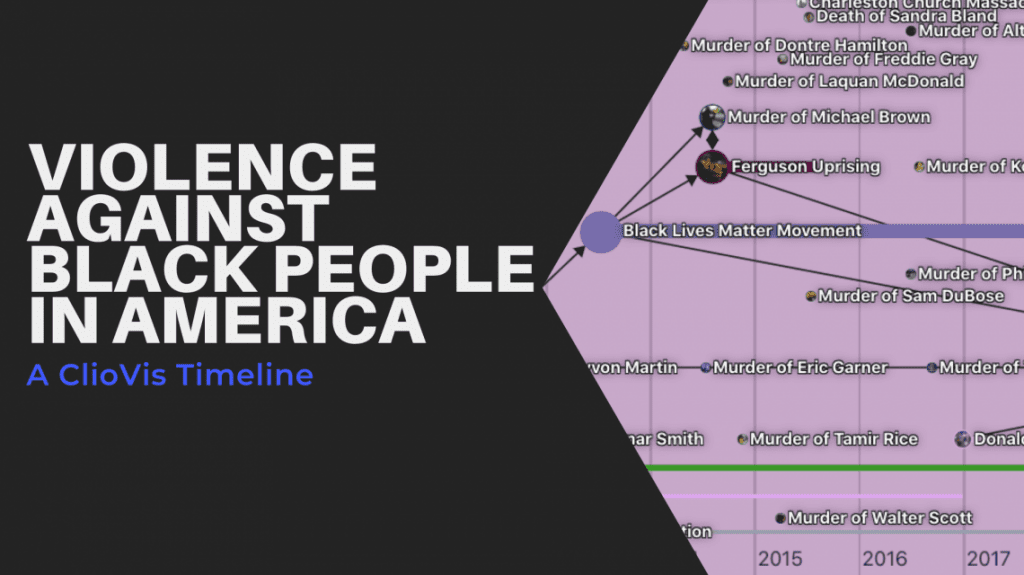

The brutal killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis this summer marked a key event in the history of violence against Black Americans. But it was just one of many acts of violence that have been committed in American history. In order to put Floyd’s killing into a larger historical context, our Digital History intern, Haley Price, created four ClioVis timelines to help herself and others learn more about such violence. Alina Scott, a graduate student in the History Department at the University of Texas at Austin and Dr. William Jones, a recent Ph.D. from Rice University, also worked on the timelines, adding relevant scholarship to many of the events to assist readers who want to learn more. Below, Haley, Alina, and Will introduce the timeline by telling us how the timelines were compiled, what they learned in making them, and how they think the timelines can serve as a resource for others. While the timelines are not comprehensive, they provide viewers with a sense of the historical forces at play across time and illustrate how the murder of George Floyd in the summer of 2020 fits into a larger pattern of historical violence.

As readers will see, there are four timelines. We originally started making one timeline. But, as the number of events grew, we decided to break the larger timeline into three separate timelines. You now see an “Overview” timeline that includes 153 events. We then divided the overview timeline into three thematic timelines: “Slavery in America,” “Jim Crow to Civil Rights,” and “Police and Civilian Brutality.”

Introduction

By Haley Price

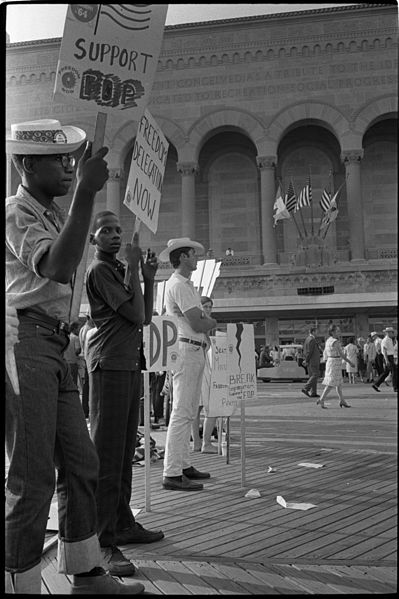

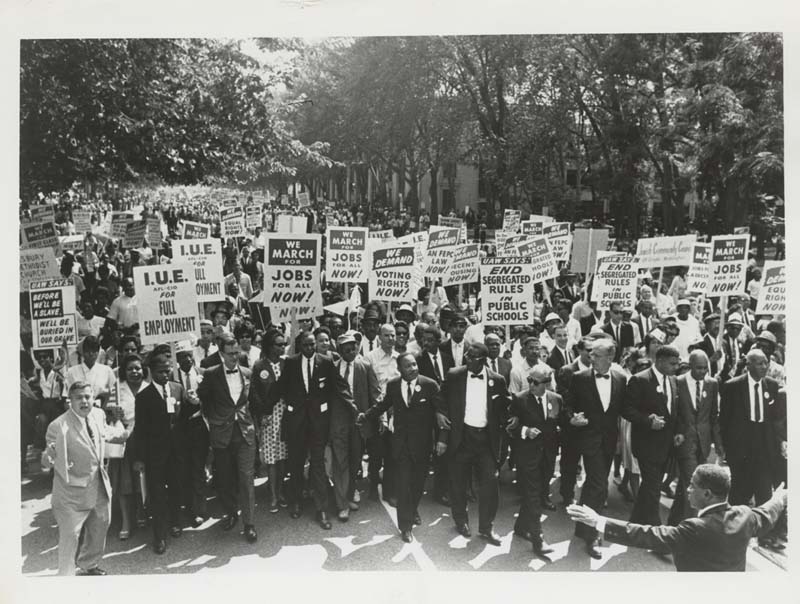

The purpose of these timelines is to visualize the history of Black Americans and to connect the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests to their historical context. Even as a History and Humanities major, this part of US history was still very new to me. I had learned about “Jim Crow Laws,” “The Great Migration, and “The March on Washington” in my entry-level U.S. history classes, but they were often tacked onto the ends of units, a footnote in a whitewashed version of our past. Black history is not given its rightful space in the American history curriculum. It is no wonder many Americans feel unprepared to fully understand the June 2020 protests.

Making this timeline was a way for me to educate myself, but much more importantly, I hope it will be a helpful resource for others to do the same. If you take one look at this timeline and feel overwhelmed, I encourage you to push past that feeling. Pick one event that you recognize and start there. See what caused that event and then look at its impact. Take things slowly, learn a little bit at a time, and then share with a loved one who wants to learn, too.

What I Did:

As I added events and eras to the timeline, I filled in their dates and wrote descriptions, added images, connections to other events, and more. I predominantly used information from websites like history.com, blackpast.org, and recent news articles. These sites fall into the category of popular history, so they are accessible to all kinds of learners. I was encouraged to find so much information through simple web searches because that means that viewers who want to go beyond the timeline will be able to do the same.

To Use ClioVis timelines:

- Click on points, connections, and eras to read about specific events and people.

- View in presentation mode to navigate the timelines chronologically.

- Zoom in and out of periods to see how historical events are connected to each other.

- Drag your mouse left and right to navigate the timeline manually.

View “Overview: Context for the 2020 BLM Protests” in full screen here .

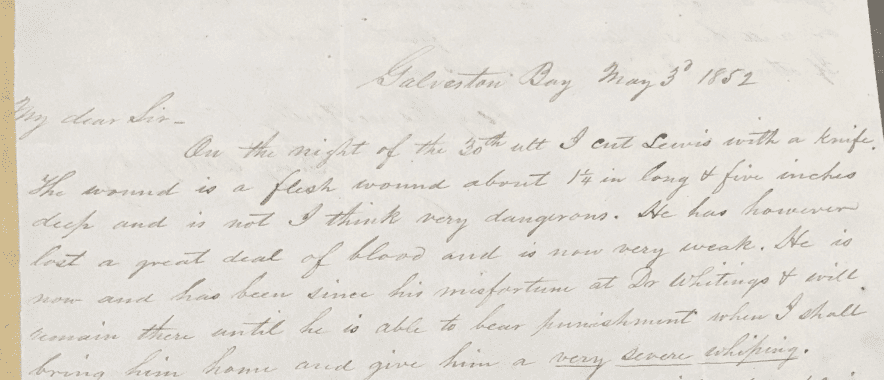

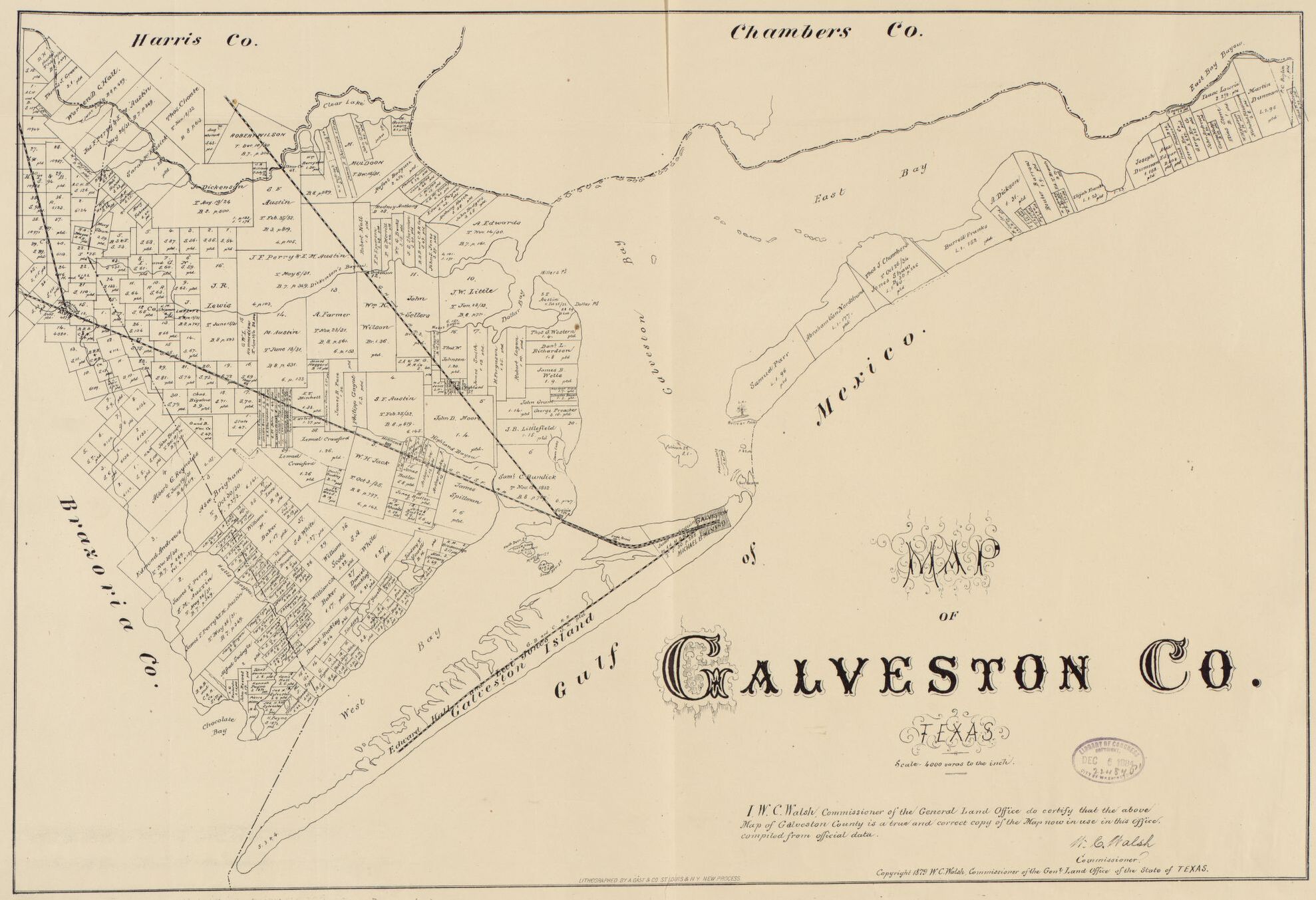

I. Slavery in America

View “I. Slavery in America” in full screen here.

What I Did:

By Dr. William Jones

I edited the timeline for content, grammar, and punctuation, focusing on the years before 1860. I also added academic sources that both substantiate the descriptions of the events and point viewers to additional reading. In choosing representative scholarship, I attempted to stick to academic sources that are comprehensive narratives published recently or considered classics. I found that describing the events themselves and finding sources for them was less difficult than deciding what should be included on the timeline. I always felt an internal tug between comprehensiveness, legibility, and simplicity.

A wide geographic perspective is often crucial for understanding the colonial era because all the European colonies in North America were part of larger empires, which included colonies in the Caribbean and South America. Yet I was also afraid of adding too many events to the timeline and making it illegible. For some events, I decided to include geographically broad connections in the descriptions rather than enter them onto the timeline. For instance, the authors of the South Carolina Slave Code of 1691 based that code on Jamaica’s code of 1684, which itself was based on Barbados’s code from 1661; this information (and sources to substantiate it) is only available on the timeline in the description of the South Carolina code. In other instances, I did not mention how historical developments outside the United States influenced a specific event on the timeline, but viewers who consult the readings will find that information. For instance, the nineteenth-century Atlantic slave trade in the Spanish Empire, sugar production in Cuba, and Great Britain’s attempts to police the slave trade on the west African coast are all background elements of the Amistad case, but none of that appears on the timeline. Finally, I felt like I needed to include some events (the Haitian Revolution, in particular) that occurred beyond the geographic boundaries of the United States because they influenced a great deal of the history of slavery and race.

II. Jim Crow to Civil Rights

View “II. Jim Crow to Civil Rights” in full screen here.

What I Did:

By Alina Scott

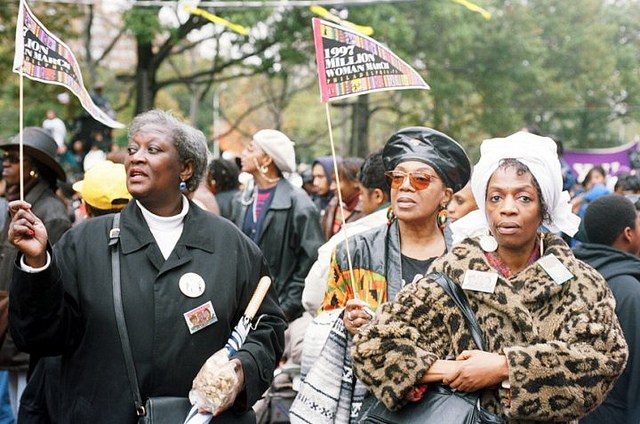

“My role in the project was to edit the period after 1860 for content and source material to ensure that Black voices and scholarship were included in the dialogue. The Black radical tradition and the movement for Black lives have a rich legacy of cultural, political, and historical contributions so incorporating novels, critiques, and histories by Black authors was not difficult. I also wanted to incorporate sources that are accessible to an audience outside academia by including e-books, podcasts, and documentaries available online.

As noted above, we divided the “Overview” timeline into three sections for the sake of user readability, though the timelines are best read together. A key goal of the project is to show the continuity of antiblackness from the highest levels of government to state leaders and local organizations. The project also shows the continuous resistance and resilience of Black people to systemic oppression.”

III. Police and Civilian Brutality

View “III. Police and Civilian Brutality” in full screen here.

“While revising, I was struck by the way the timeline highlights protest, legislation, and presidential power as key themes. While it includes a large number of important individuals, organizations, and events, the timelines is incomplete. Overall, the timelines do a tremendous job highlighting key dates in Civil Rights activism and legislation even if it was not possible to include all historical actors and events. They make an excellent tool for teaching and learning about the political genealogy of the historic moment we are currently in. The movement for Black Lives is bigger than politics and legislation and we encourage others to make their own timelines. For instance, how might this timeline overlap with another on Black life, joy, and healing practices? Or a timeline centering Black Women and their role as intellectuals, in community building, religious life, and organizing? Or a timeline on Black Internationalism, international BLM movements, or coalition-building in the African Diaspora? There is potential, with a tool like ClioVis, to digitally show the many ways Black people have advocated for our lives and liberated ourselves in a way that is historically accurate, representative, and educational.

We hope you find thatthe timelines a useful building block for teaching and learning history.”

If you would like to know more about using these and other timelines or use ClioVis in your classroom, contact admin@cliovis.org.

Visit ClioVis.org for more information on how to create an account, view tutorials, and other sample projects.

You Might Also Like: