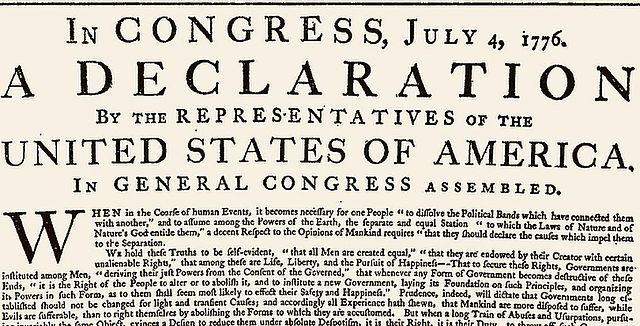

The expectation that the United States of America would become an empire in its own right is enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. In his new book, Eliga Gould contends that when the delegates to the Continental Congress of 1776 asserted the United States’ right “to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them,” they were declaring their right to colonise peoples and lands that had not yet been conquered by European powers. Instead of offering an alternative to the European empires, the new United States sought to mimic them. The colonists’ imperial ambitions lay at the heart of the nation-building project.

The expectation that the United States of America would become an empire in its own right is enshrined in the Declaration of Independence. In his new book, Eliga Gould contends that when the delegates to the Continental Congress of 1776 asserted the United States’ right “to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them,” they were declaring their right to colonise peoples and lands that had not yet been conquered by European powers. Instead of offering an alternative to the European empires, the new United States sought to mimic them. The colonists’ imperial ambitions lay at the heart of the nation-building project.

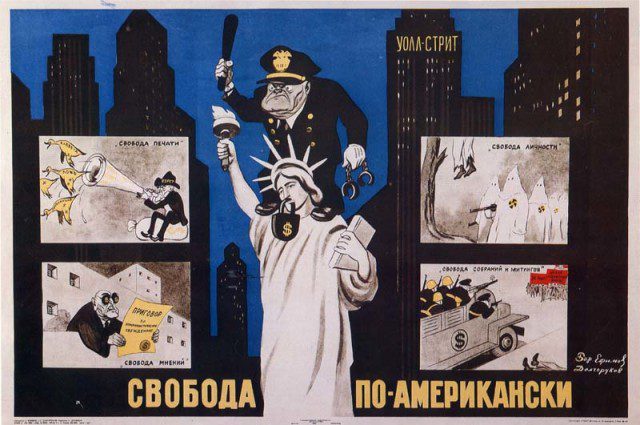

The significance of “among the powers of the earth” has been marginalized in the endless popular and scholarly discussions of “the most treasured national relic.” Gould is not the first historian to deconstruct the Declaration’s preamble in a way that forces us to rethink the origins of the independent United States of America. In his “Global History” of the Declaration, David Armitage recognised the pertinent phrase “among the powers of the earth” as evidence that European leaders were the Declaration’s primary audience. He emphasised that the proclamation “sought the admission of the United States to a pre-existing international order;” it was an inherently conservative statement that “signalled to the world that their revolution would be decidedly un-revolutionary.” Yet Armitage did not make explicit that the United States defined itself, from the very beginning, as an empire. This uncomfortable underbelly of the Declaration of Independence prompts us to reconsider claims that the American Revolution constituted “the first of the modern era’s great liberationist events.”

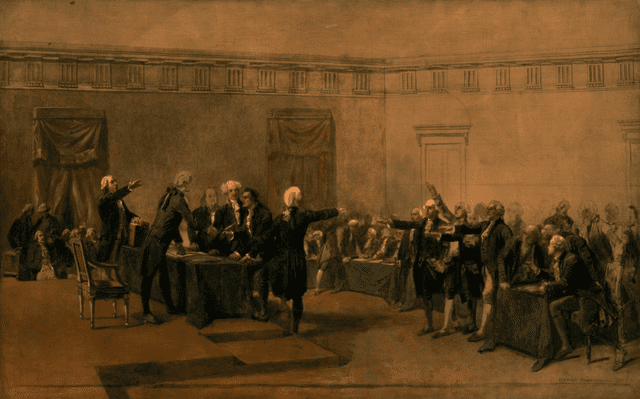

The Declaration of Independence of the United States of America, by Armand-Dumaresq, (c. 1873). Via Wikimedia Commons

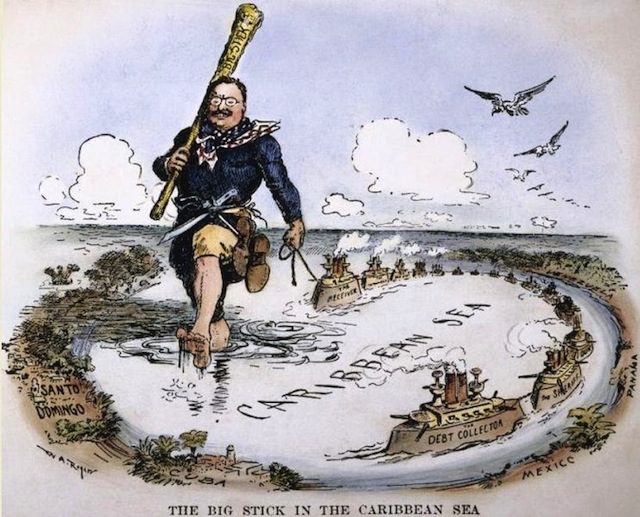

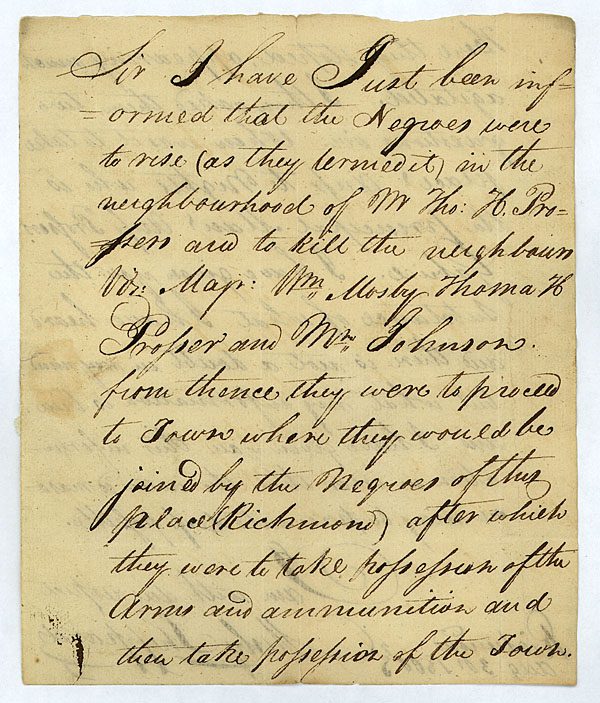

Moving forward from the American War for Independence, Gould explores the emergence of the idea and reality of a United States empire though the analysis of Union diplomacy in the decades leading to the First Seminole War (1816-1819) and the adoption of the Monroe Doctrine (1823). Gould pays close attention to the development of political relationships between the United States federal government and its citizens, and European and Native American leaders and their emissaries. It is less concerned with the dry details of specific international treaties than with the “broader process by which Americans sought to make themselves appear worthy of peaceful relations with other nations.”

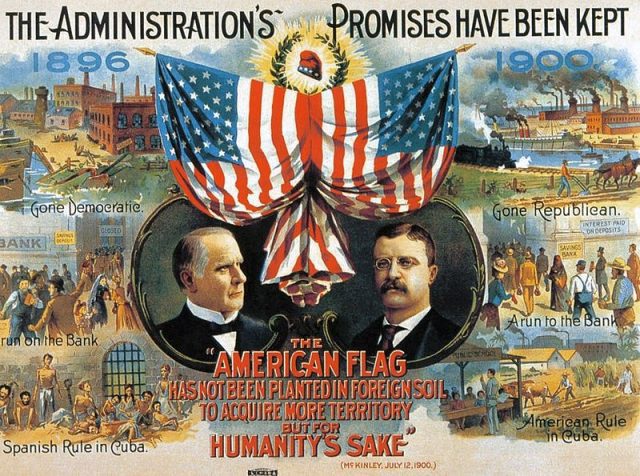

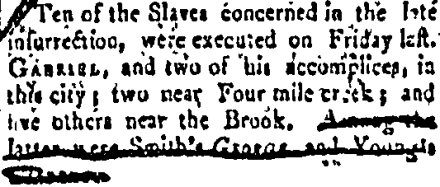

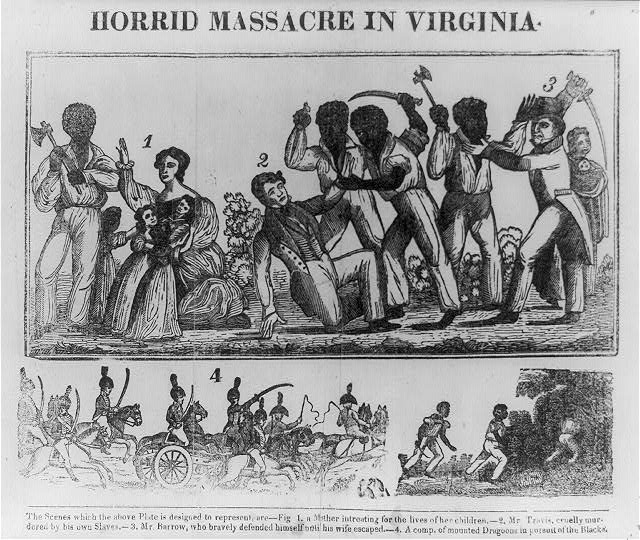

In this account we discover that treaty-making ultimately succeeded in protecting the right of US citizens to own slaves and dispossess Native Americans of their lands. North American slave-owners successfully used British legal precedents to defend the legality of plantation slavery. The outbreak of war in Europe also influenced the survival of slavery and the rapid expansion of the United States into Indian territory. Gould suggests that European powers, particularly Britain and Spain, were less willing and able to fight against slavery and support their indigenous allies against the American behemoth when confronting Napoleon’s army demanded their attention and resources. In this way Among the Powers of the Earth makes a convincing case that the history of the United States cannot be studied in a vacuum. At its core the evolution of the United States was deeply entangled with the European empires whose ranks it wanted to join.

Gould’s Atlantic focus, however, keeps him from grappling with the fact that European empires were aggressively expanding in the period he considers. For example, as the Union army marched into Creek and Seminole territory, British soldiers and convicts invaded Aboriginal lands in Australia and India, and Spain was working to extend its network of missions, forts, and trading posts into northern Mexico and the Pacific northwest of the American continent. Surely European powers’ ongoing campaigns to expand their empires in the Pacific and Indian Ocean worlds affected their readiness to accept the Union’s violent push into Florida? Gould’s Atlantic focus leads him to give an imbalanced account of how the law of nations vis à vis imperial economic interests shaped Europe’s responses to the American empire.

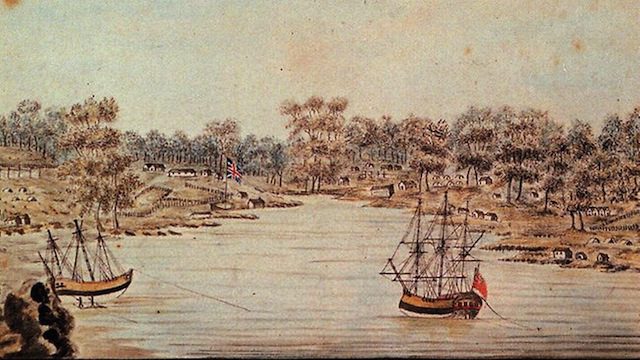

An oil painting of indigenous Australians watching Captain Phillip’s First Fleet arriving in Sydney Cove, 1788. Courtesy of the Mitchell Library.

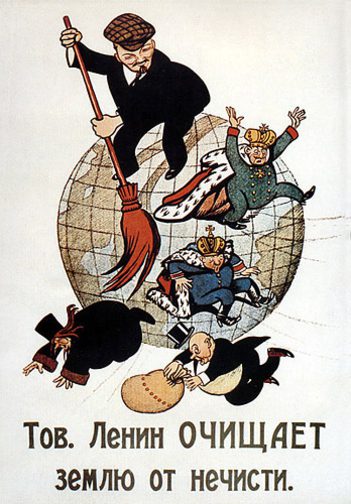

Had Gould turned his critical gaze towards the Pacific, he could have more forcefully challenged the dominant narrative about the Age of Revolutions. Gould’s findings have implications far beyond American history. Among the Powers of the Earth disrupts the mantra that the Age of Revolutions ushered in the Age of Nations. It makes an important contribution to the recent wave of historical research that destabilises the notion that the bloody rebellions that erupted in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were fundamentally anti-colonial and democratising in their aspirations and impact. Gould belongs to the school of historians who consider the period from 1760 to 1830 as “the first age of global imperialism,” as C.A. Bayly put it. Other new and noteworthy revisionist monographs include David Lambert’s history of the pro-slavery movement in the Anglo Atlantic World (2013), and Gabrielle Paquette’s study of the nineteenth-century Portuguese monarchy and empire (2013). The Age of Revolutions was more complex than romantic myths of national election seem to suggest.

Eliga Gould, Among the Powers of the Earth: The American Revolution and the Making of a New World Empire. (Harvard University Press, 2012).

More in the Entangled Histories series on Not Even Past:

Bradley Dixon, Facing North From Inca Country: Entanglement, Hybridity, and Rewriting Atlantic History

Ben Breen recommends Explorations in Connected History: from the Tagus to the Ganges (Oxford University Press, 2004), by Sanjay Subrahmanyam

Christopher Heaney reviews Poetics of Piracy: Emulating Spain in English Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) by Barbara Fuchs

Jorge Esguerra-Cañizares discusses his book Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-170 (Stanford University Press, 2006) on Not Even Past.

Renata Keller discusses Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 (Yale University Press, 2007) by J.H. Elliott

You may also enjoy:

David Armitage, The Declaration of Independence: A Global History. Harvard University Press, 2007.

C.A. Bayly, “The First Age of Global Imperialism, C. 1760–1830.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 26, no. 2 (1996): 28-47.

David Lambert, Mastering the Niger: James MacQueen’s African Geography and the Struggle over Atlantic Slavery. (University of Chicago Press, 2013)

Garielle Paquette, Imperial Portugal in the Age of Atlantic Revolutions: The Luso-Brazilian World, c. 1770-1850 (Cambridge University Press, 2013)