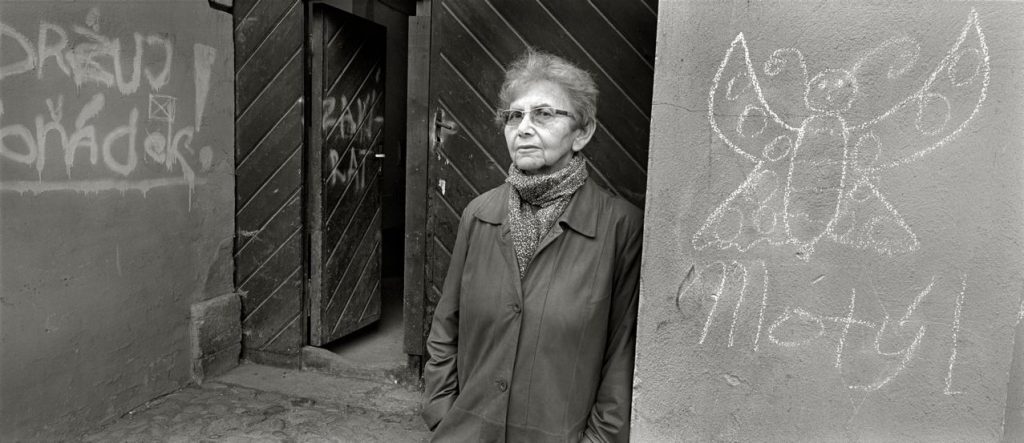

My grandmother, Ewa Janik, was born in late August 1942 to a Jewish family in the heart of Nazi-occupied Poland. As the Gestapo approached her family’s ghetto, her parents arranged for her to be smuggled away by members of a local underground organization opposing Nazi rule. From two weeks old, my grandmother was raised by a Catholic adoptive family, and she remained unaware of her true origins until the age of sixteen, when her surviving relatives hired a lawyer to contact her. Over the following decades, she reunited with her original family, eventually moving to the California Bay Area to live near her birth mother, who had escaped there after the war.

Ewa Janik’s story fits into the general category defined by Holocaust researchers as Hidden Children. At the onset of World War II, approximately 1.7 million Jewish children under the age of 16 were living in Europe, and would become major targets of Hitler’s genocidal agenda.[1] As anti-Jewish policies were increasingly enforced in Nazi-occupied Europe, these children and their families adopted various strategies to evade German forces, and a significant portion survived by living in hiding. Those who were young or fair enough to blend in with the wider European society were able to hide “in plain sight,” sheltered by Christian families or religious organizations. After the war, these children often found themselves caught between two worlds, with conflicting cultural and familial ties to both their adopted Christian upbringings and their Jewish family heritage.

Janik with her adoptive mother Zosia, ca. 1945. Source: Zofia Graham

My grandmother has recorded her life story in several oral history interviews, both through the Bay Area Holocaust Oral History Project in 1997 and in recent interviews with me. A major tool used by historians and memorial organizations, oral testimonies can help convey the personal and emotional experiences of Holocaust survivors in ways that written history often cannot. Analyzing individual stories provides insight into how survivors respond to their circumstances and how these effects can persist throughout their lifetimes. The topic of personal identity is a major theme throughout the testimonies of former Hidden Children, such as my grandmother, revealing the psychological impact of their shared childhood experiences on future self-conception.

My grandmother’s interviews reveal complex and changing attitudes toward her personal and cultural identities throughout her lifetime. Upon first learning of her history and original family as an adolescent, she describes feeling intense fear and instability, stating in her account of that time, “I always [felt] like I don’t have a ground under my feet. Something will happen and everything will collapse.” Due to the pain of this revelation, she expressed that she wished both sets of parents had taken greater pains to make sure she would not find out her history. These feelings reflect many Hidden Children’s experiences of alienation due to the fracturing of their childhood identities, as demonstrated by historical and psychological research on the subject. For example, a 2005 study by psychologists Marianne Amir and Rachel Lev-Wiesel revealed that child Holocaust survivors who lost their prewar identities faced significantly higher rates of depression and anxiety compared to those who knew their birth families.

After discovering her Jewish identity, my grandmother faced additional difficulties due to the resistance from her adoptive parents. Even after the secret was revealed, her parents refused to acknowledge or speak about the topic, viewing such questions as an affront to the effort they put into raising her. As she began communicating with her birth relatives, she had to proceed in secret, and she shared the great pain this brought her, stating, “I felt like both my mothers would cut me in half.” Even as an adult in 1997, she expressed shame for hurting her adoptive family by moving to the United States, stating that “no matter what I do and where I am, I’m here and my mother in Poland is hurting.”

Cultural and religious identifications presented another source of strain. Unlike many Hidden Children, my grandmother was not raised in an antisemitic environment. Still, she had little knowledge of Judaism as a child, and what little she knew was influenced by the society around her. In our recent interview, she described an instance from her childhood when another child called her Jewish in a derogatory way, and she didn’t understand what he meant or why he was saying it. Once she learned of her true heritage, she had to become newly acquainted with Judaism as a member of the community, and with new traditions and practices which were completely foreign to her.

Janik with her biological mother Irene, 1978. Source: Zofia Graham

These cultural differences brought on struggles when trying to reconnect with her biological family. She describes the difficulty of her first visits to the United States, when she finally met with her American-born siblings, but had no language with which to communicate or the ability to understand their vastly different life perspectives. Such experiences of separation led her to speak negatively about her divided identities in her 1997 interview, stating, “What else is painful, that I belong to two cultures, and I don’t belong anywhere really.”

However, despite these challenges, my grandmother has more recently emphasized the positive aspects of her mixed cultural identities. She has become more comfortable claiming her Jewish identity along with her Polish one, largely through the help of her American Jewish family, who she has always described as supportive and accepting of both their cultural differences and commonalities. She celebrated her ability to traverse and learn from multiple cultural and religious communities, reflecting that this perspective has allowed her to see the value in multiple traditions and beliefs without becoming attached to dogma. These constructive takeaways are also reflected in the academic literature. While much research studying Hidden Children has rightly focused on their trauma and pain, there is also significant evidence for the resilience and success of this group. Psychiatrist and researcher Robert Krell describes the “enduring mystery” of how child Holocaust survivors have been able to find general success as adults despite their immeasurable trauma in early development.[2] Perhaps the influence of distinct cultures and life perspectives in the development of Hidden Children has played a part in their lasting psychological fortitude.

Janik (third from left) with her siblings, 2024. Source: Zofia Graham

This past summer, my entire extended family returned to Poland, where my grandmother led us through sites from our family’s history: her birth parents’ apartment in the Jewish Ghetto, the work camp where her mother was held during the war, and the memorial site where Nazi soldiers shot her biological father at the start of the occupation. These recollections brought back pain and trauma for all involved, but my grandmother reflected with surprise that her loved ones’ care and interest in these stories helped to ease her mental toil. For someone who felt alone for much of her life, the ability to share the burden of the past with all of her diverse family members has been an essential element in healing.

Zofia Graham is a 4th year undergraduate student at UT Austin. She is majoring in Linguistics and Plan II Honors, with a minor in Law, Justice, and Society. Her research mainly focuses on Latin American linguistics and language policy, but she has enjoyed diving more into her family history through this project.

[1] Greenfeld, Howard. The Hidden Children. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1993, p. 2.

[2] Glassner, Martin Ira, Robert Krell, and Holocaust Child Survivors of Connecticut. And Life Is Changed Forever: Holocaust Childhoods Remembered. Edited by Martin Ira Glassner and Robert Krell ; Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2006, p. 8.

Additional bibliography:

Amir, Marianne, and Rachel Lev-Wiesel. “Does Everyone Have a Name? Psychological Distress and Quality of Life Among Child Holocaust Survivors with Lost Identity.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 14, no. 4 (October 2001): 859–69.https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013010709789.

Janik, Ewa. Interview by Author. April 3, 2025.

Janik, Ewa. “Oral history interview with Ewa Janik.” By Liz and Peter Ryan. The Bay Area Holocaust

Oral History Project. March 23, 1997. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn508375 Libicki, Henry. Remembering my Parents. Self-published. 2010.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.