Robert Runyon was an astoundingly prolific photographer of the Texas-México borderlands at the turn of the twentieth century. The University of Texas at Austin hosts over 14,000 photographs donated by the Runyon family, along with related manuscript materials. Much of the collection is available digitally, and the Briscoe Center for American History also houses Runyon’s glass negatives, lantern slides, nitrate negatives, prints, postcards, panoramas, correspondence, and business records.[1] The sheer scope of his work, which ranges from botanicals to portraiture to quotidian scenes of daily life, has rendered his imagery—in regard to Texas and the U.S.-México border—ubiquitous.

Over the last century, Runyon has maintained an undisputed centrality in our historical thinking about the borderlands—his images have been utilized as illustrations and as evidence by both journalists and historians. Runyon’s success in accessing spectacular events and in producing and marketing a massive number of images of México and south Texas as a commercial, souvenir, postcard, and portrait photographer rendered him the author of a broad and seemingly authoritative visual truth. Crucially, however, there has been a narrow focus on photographs of spectacular violence taken during a less than ten-year period.

The focus on images of carnage was likely driven by the publication of War Scare on the Rio Grande: Robert Runyon’s Photographs of the Border Conflict, 1913-1916, which focused on this narrow period of his career and solidified Runyon as a combat photographer.[2] In fact, in the inventory of the photographic collection at the University of Texas at Austin where the bulk of Runyon’s work resides, less than three percent of his photos feature the spectacular violence of Mexican Revolutionary engagements, the train wreck at Olmito, or the bodies of Mexican men in Norias, Texas, for which he is most recognized.[3]

The enormous archival collections related to Runyon allow for a fuller picture (pun intended) of Runyon’s work. Abandoning the notion of Runyon as a documentarian, or as a photojournalist, enables us to study the implications of Runyon’s career trajectory as a commercial photographer and someone who perpetually re-invented himself to build and to serve a profitable market. The archive donated by Runyon’s family—and the associated collections in which Runyon’s correspondence, notes, and field books appear—facilitates removing the “documentary” lens that has been wrongly applied to Runyon’s visual productivities. Further, spending time with the documents allows us to become more attentive to Runyon’s massive photographic output as the result of not quite a family business—Runyon’s thousands of images exceed the structural outline of such an enterprise. For instance, Runyon’s decades of work along the Texas-México border were accomplished through the networks made accessible by his wife Amelia Medrano and her family members. The unusual richness of access to south Texas, Matamoros, and even the Mexican Revolutionary armies came via the Medranos. Further, much of the labor of preserving and developing from glass negatives (some of the Runyons’ own manufacture) was assisted by his wife, and later by his son Delbert.[4] Indeed, his daughter Amali—later a genealogist and historian—describes acting as his research assistant, editing, and assembling Runyon’s published works.[5]

The holdings at The University of Texas at Austin give uncommon opportunities to cross-reference archival collections at the Briscoe Center for American History, which houses the Runyon Photograph Collection, with related collections at the Harry Ransom Center. Exploration of the collections re-emphasize Runyon as earnestly engaging in commercial enterprise. No matter his photographic subject—cacti or portrait, panorama, or brutal execution—Runyon constructed his images for income. The self-trained photographer posed subjects as varied as: families for portraits, cotton harvesters, and the remains of Mexican men killed by Texas ranchers and Texas Rangers. In every case, he constructed compositions assessing commercial viability, and making editorial decisions for his photos.

Training a Commercial Eye

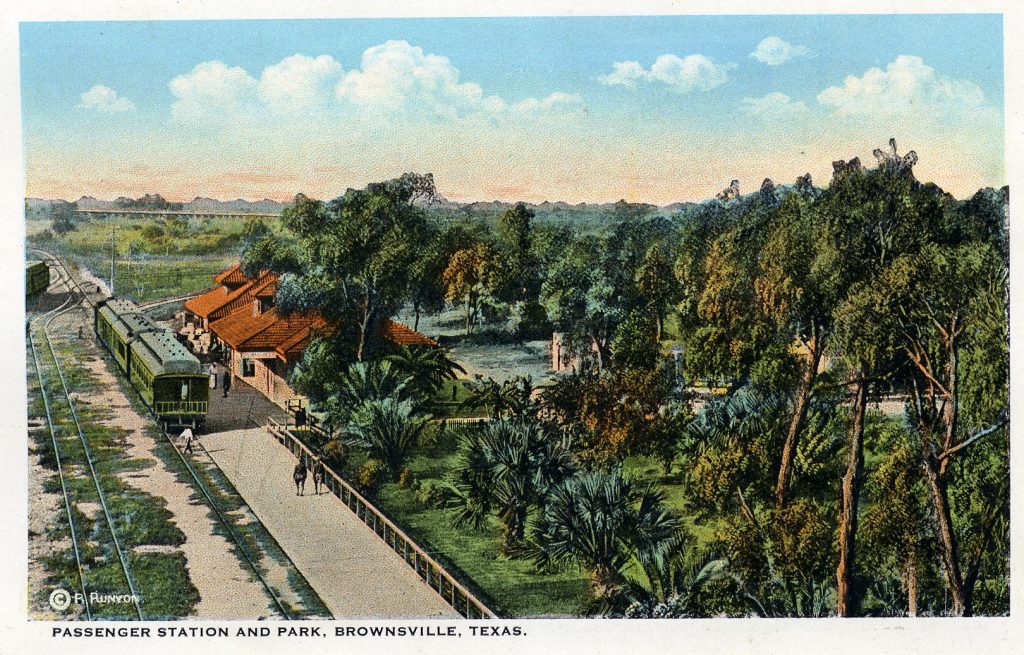

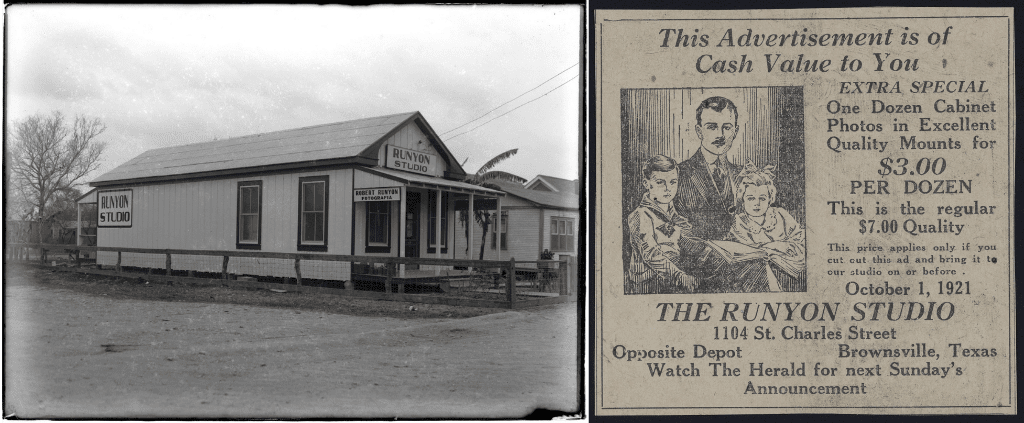

Robert Runyon, born in Kentucky, was an insurance salesman in Ohio who made his way to Texas after the death of his first wife, Norah. Aiming originally for New Orleans, the twenty-eight-year-old widower and father of a five-year-old son (who Runyon left with his maternal grandparents and sent for later) found work with the St. Louis, Brownsville, and Mexico Railroad in Houston. After some time in the Houston depot, he was made manager of the lunchroom and curio shop in the Brownsville Station.[6] From April 1909 until 1912, Runyon managed the shop and Gulf Coast News Company’s news stand, engaging with travelers to, from, and through Brownsville.[7] Runyon ran the shop, and ordered fixtures and supplies, and the extant records demonstrate his expansion of tourist trinkets into a larger postcard inventory. A sampling of invoices and receipts from postcard dealers that Runyon ordered from for the Gulf Coast News shop are available in his surviving business records. Runyon also purchased additional postcard racks to display these profitable items.[8]

While “selling fruit candy and cigarettes to the passengers,” Runyon, the Kentuckian employee who was renting a small room across from the train depot had a shrewd revelation.[9] Reporter James Pinkerton explains, “Runyon, an amateur photographer, figured he could bank money producing and selling his own postcards of the emerging cultures on both sides of the Rio Grande. By 1911 he had quit working for at the tourist shop and devoted all his time to photography.”[10] Further, as not only the shop clerk, but also the person stocking and ordering postcards from various manufacturers, Runyon had been able to translate his dedicated attention—on company time—into market research. In the small lunchroom and curio store of the Brownsville, he was able to refine his photo choices and to capitalize by mimicking successful postcards.[11] Runyon’s photography career, begun as early as early as 1910, developed concurrently with his studied expertise of the souvenir demands of tourists.

As he cultivated postcard subjects, Runyon also began to diversify his possible customer base. Photographs in the Runyon Collection suggest that the young photographer focused on outdoor rural still lifes, emphasizing the budding agricultural wealth of the region. Early images from 1912 construct a rugged—yet orderly—bounty, as displayed at that year’s mid-winter Brownsville Agricultural Fair. Stacked award-winning cabbages, turnips, and citrus fruits were among the cameraman’s first surviving subjects. Inanimate, compliant, posable crops and their proud growers would not only prove relatively easy studies for a self-teaching photographer, the images were also a canny market choice.

Runyon was working to draw a specific viewer and customer by demonstrating his skills in staging, lighting and shadow, as well as establishing a photorealistic style, showing the fine grain detail possible with his equipment. He purchased used equipment and lenses, and various developing papers, to improve his work’s brilliancy and gradation. It is critical to note the context of production of Runyon’s early still lifes. Participating in the imagination of south Texas as the American tropics, Runyon’s early pictures were not simply produce photography, they were product photography. Although it was not visible in the frame, the focus was unerringly on the fruits of Texas land.

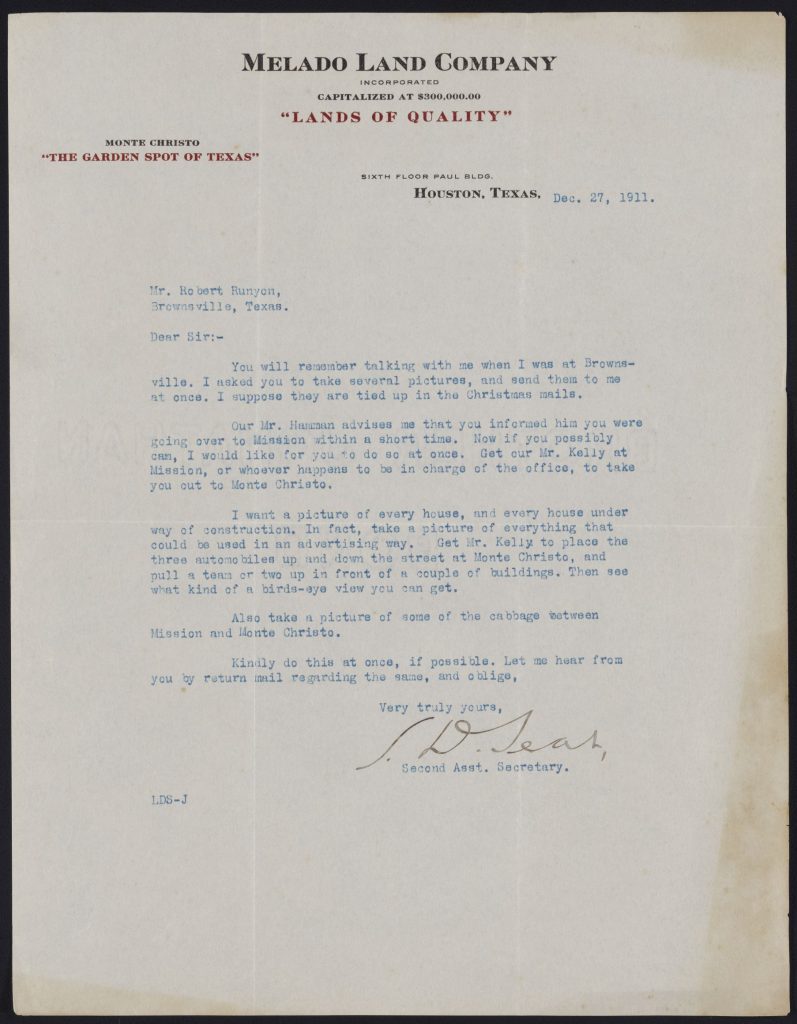

By demonstrating an ability to render abundance—the fruits of a fertile land—the photographer, still early in his postcard-making career, added an additional and profitable audience—regional developers and real estate boosters.[12]. Investors and developers were quick to enlist Runyon in their schemes and he obliged, offering his emerging talents in service of the land companies. As he continued to learn his craft, with his son William Thorton now at his side, Runyon began doing promotional photographs for enterprises like the Melado Land Company near McAllen. Melado, founded in 1909 by Marshall McIlhenny in Houston, was a series of subdivisions—cleared land, separated into six hundred and forty family plots, with water drilled by Melado. The subdivided community came to be called “Monte Cristo” and soon had retail stores, a lumberyard, a post office, and even its own newspaper—The Hustler.[13] When Melado hired Runyon, they began by asking about images he may have taken previously, but quickly shifted to requesting that he capture specific scenes, writing in July of 1911, “At this time we are particularly anxious to secure a picture of the cotton field wherein the bolls are open, and the cotton is hanging there from. If you have no such picture at hand could you not go out and obtain one…?”[14] Throughout 1911, Melado corresponded with Runyon confirming their photo orders, sending payment and receipts of photos, and making additional requests for scenes from both sides of the border.

In Texas, Melado hoped for pictures of Fort Brown Reservation, palm groves, and the Government Experimental Farm in Brownsville, and across the border, “some Mexican scenes such as street cars in Matamoros, the homes of Mexicans and so forth.” In addition, echoing back to Runyon’s successful agribusiness images, the developer calls for “growing crops, such as corn, sugar cane, sorghum, milo maize and so forth . . . as likewise, if you have any pictures of orange trees, lemon trees, or grapes, we should like to have them.”[15] The widower with his son—about 1,400 miles away from his closest family—filled Melado’s orders as requested. The photos demonstrating a rich, new Texas modern were not documentary, the photos were of specific objects and scenes—solicited as advertisements. Each image was requested in the service of a commercial and pointedly progressive, expansionist narrative. By December of the same year, Melado was giving Runyon instructions on how to stage particular pictures:

I want a picture of every house, and every house under way of construction. In fact, take a picture of everything that could be used in an advertising way. Get Mr. Kelly to place the three automobiles up and down the street at Monte Cristo, and pull a team or two up in front of a couple of buildings. Then see what kind of birds-eye view you can get.[16]

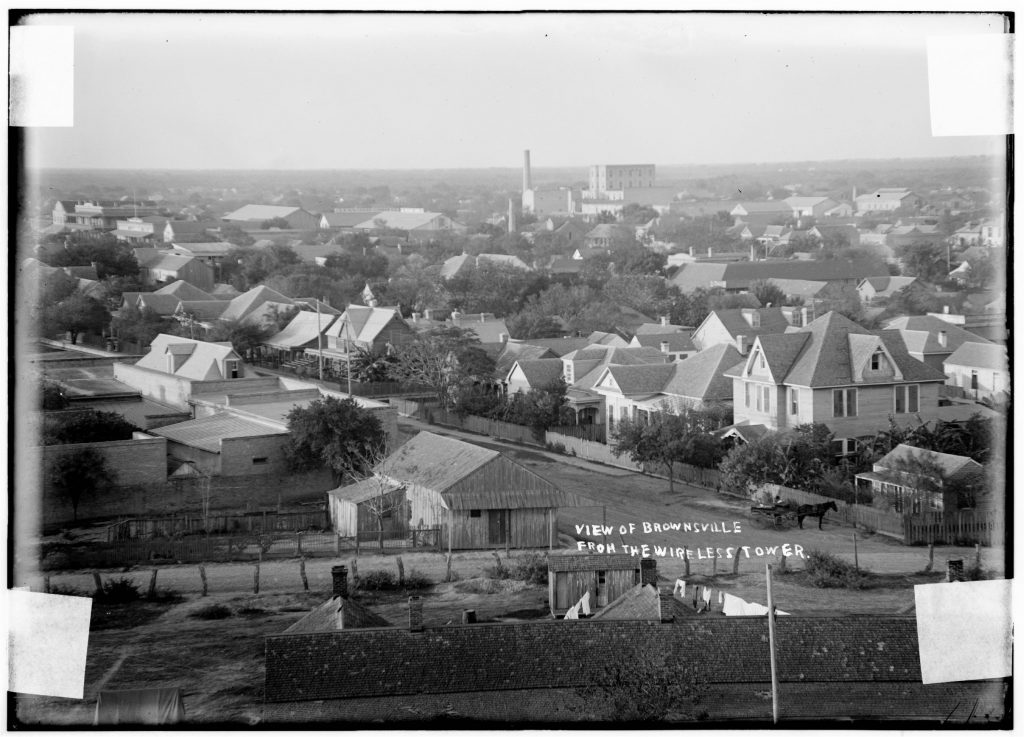

Runyon’s business records give us an important opportunity to reflect on the distinction between an image being representative of historical truth versus an image being representative of a market. Runyon joined his postcard and developer images not only in subject matter. He was certain to remind area businesses like the Gulf Coast News gift shop to order his postcards to serve the incoming land customer base, writing “the season is almost here for the Homeseekers and you will want Post Cards and I have the cards to sell.” [17] Runyon increasingly utilized birds-eye view, as suggested by Melado and he added equipment to produce panoramic landscapes. Indeed, he etched his physical efforts into his photos, such as with “View of Brownsville from wireless tower.” Such images would work not simply to document, but to promote growth and “American progress.” The photographer perched high, and his sympathetic viewer would be positioned as powerful masters of a newly and violently taken landscape.

Reframing Attacks

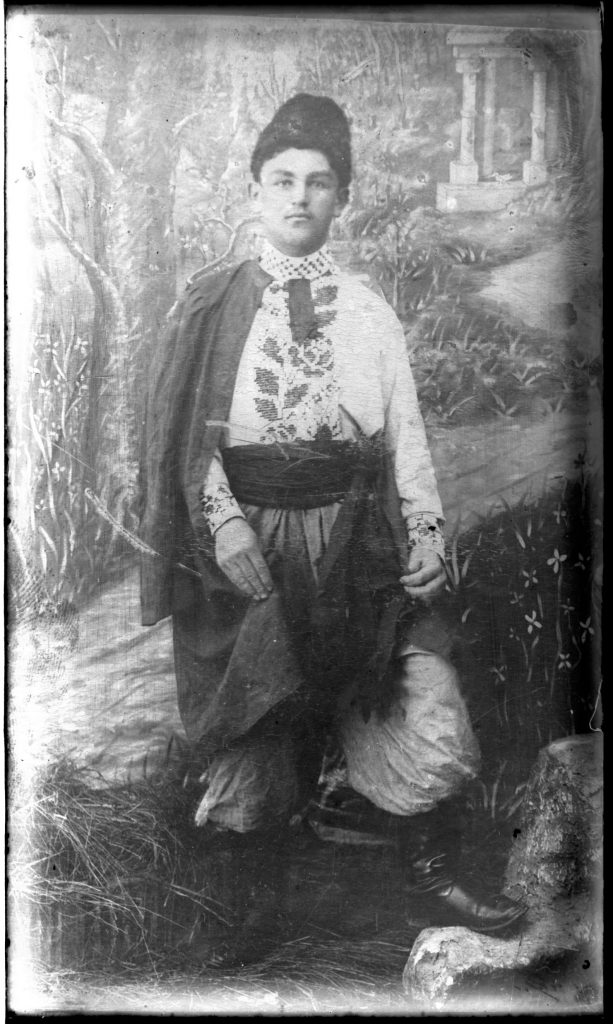

The itinerant Runyons’ fortunes turned when he married an upper middle-class Mexican woman, Amelia Medrano in 1913. Medrano’s relatively wealthy and well-established family from Matamoros was headed by her father, José T. Medrano. Medrano had attended Seton Hall in New Jersey as the U.S. Civil War raged. His cosmopolitanism resulting from U.S. East Coast residential Catholic schooling allowed Medrano to boast of being in New York City as U.S. President Lincoln was assassinated in nearby Washington, D.C. [18]

After their marriage in 1913, Amelia would raise his son, William Thorton, from his first marriage, and would assist with his photography—helping him to develop and preserve heavy glass negatives. Further the Medrano family’s significant network on both sides of the Texas-México border would give Runyon privileged access, such as when “Runyon’s brother-in-law a member of the rebel army that attacked Matamoros obtained permission for Runyon to travel with the troops,” according to photographic curator Lawrence A. Landis.[19] Indeed, as noted in The Austin American-Stateman, the year Runyon and Medrano married, began the most significant period of Runyon’s production of images of the Mexican Revolutionary troops and political leaders, scenes of battles, and of Mexican refugees in the aftermath of battle on both sides of the Texas-México border.[20]

Careful attention to the context of production of the spectacular violence images, as well as their function, is crucial. These photos are not unmediated documents, but instead carefully constructed pictures—lit, posed, and cropped—for a burgeoning consumer market. Runyon would stage the leavings of events, including dead bodies, with the help of local participants. The photographs Runyon produced and often sold as postcards between 1913 and 1916 recall the methods of U.S. Civil War photographers, who “invented their own photographic iconography of war,” and who learned that “none of their pictures garnered more public attention than those that showed the carnage of battle.” [21] Like Alexander Gardner, who fabricated some of the most moving images of the Civil War, including “The Home of A Rebel Sharpshooter,” Runyon arranged and manipulated scenes of carnage for his clients and customers.

Tracing the photographer’s alterations is possible due to the several photo series available where we can take note of changes to the scene that Runyon made from frame to frame. Several of his most recirculated stand-alone photographs are from a series of pictures taken at Norias in 1915.[22] Until the formidable text The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas by Monica Muñoz Martinez, these images had been employed as discrete and self-contained pictures. However, Martinez focuses on the work of Runyon by examining the series together.[23] There are thirteen original images of corpses in the series taken by Runyon, several of which include his narrative etching of “dead bandits.” The bodies of dead men are repositioned with locals posing with the bodies. Runyon indulged the living subjects in the photos, who he portrays towering over the bodies, both playful and satisfied. The photographs are shot and reshot to best convey a narrative victory for the white subjects of the photos and for those with a sympathetic relationship to white dominance in south Texas, providing in turn a proxy experience for the purchaser.

Like the Civil War combat images, as Sandweiss argues in Printing the Legend: Photography and the American West, such photos “did less to show off the fact recording capacity of photography than to suggest the ways in which photographers had learned to manipulate and arrange their subjects.” Sandweiss continues, such photos “might convey an ideal of military and gentlemanly conduct but they conveyed nothing about a particular moment in the conduct of war.”[24] And certainly in the case of the Norias images, Runyon and his subject were eager to build a visual storyline of a “bandit war,” expunging a century of anti-Mexican violence by the very kinds of new settlers to whom the Melado Land Company were selling. From the earliest periods of his career and the development of his photographic eye, Runyon’s images—from railroads to citrus to carnage—are always paired with U.S. expansion and domination of territory.

Runyon’s relatively small collection of battle and carnage photos from the Mexican Revolutionary period has received the most attention, though these images are often utilized as straightforward illustrations or evidence rather than analyzed for their cultural meaning. The interest in the stylized violence has often lacked visual analysis that points to the ways Runyon manipulated scenes and worked to convey genre expectations, similar to his counterparts during the U.S. Civil War. His images of spectacular violence continue to find an audience today, as they did during the years they were sold and sent as postcards.[25] As we examine them, we must be reminded that these are not neutral images frozen in time. Instead, they are visual texts, with an author, constructed for commercial purpose. As with U.S. Civil war visual iconography, Runyon would find “none of the pictures garnered more public attention than those that showed the carnage of battle. Lured by a ‘terrible fascination’ with the features of the slain soldiers, [viewers] thronged to marvel at the ‘terrible distinctness’ of the pictures.”[26] Runyon participated in the construction and circulation of such images, exploiting a profitable market.

His images are not a neutral record of the past—buildings as they stood, bodies as they fell—instead these photos (many of which would be sold as postcards) work like a hinge. The photos point to the cultural meaning of the demand for such images backward, and their terroristic use forward. They allow us to look backward, giving us a sense of market appetite, insights into who and what was and was not valued, who had the power and capital to commission photos, and for what purpose. They also allow us to look forward to their powerfully perennial function. As Monica Muñoz Martinez argues in The Injustice Never Leaves You,“ by selling and circulating these images, photographers ensured that the moment of racial terror survived long after the event and continued to reassert this terror in the American South. The photographs were thus both a bonding mechanism for those who shared the images and a continued method of racial intimidation.”[27] Runyon’s images were not mere reflections of popular appetites, they co-created social values. Following the path of Martinez, we must think through the punishing effects of postcards that valorized violence against Mexicans. The images of violence—though a fraction of his oeuvre—when revisited, must be seen with the understanding that Runyon manufactured these visual texts in an expansive and anti-Mexican mercantile ecosystem.

The Obscured and the Exposed

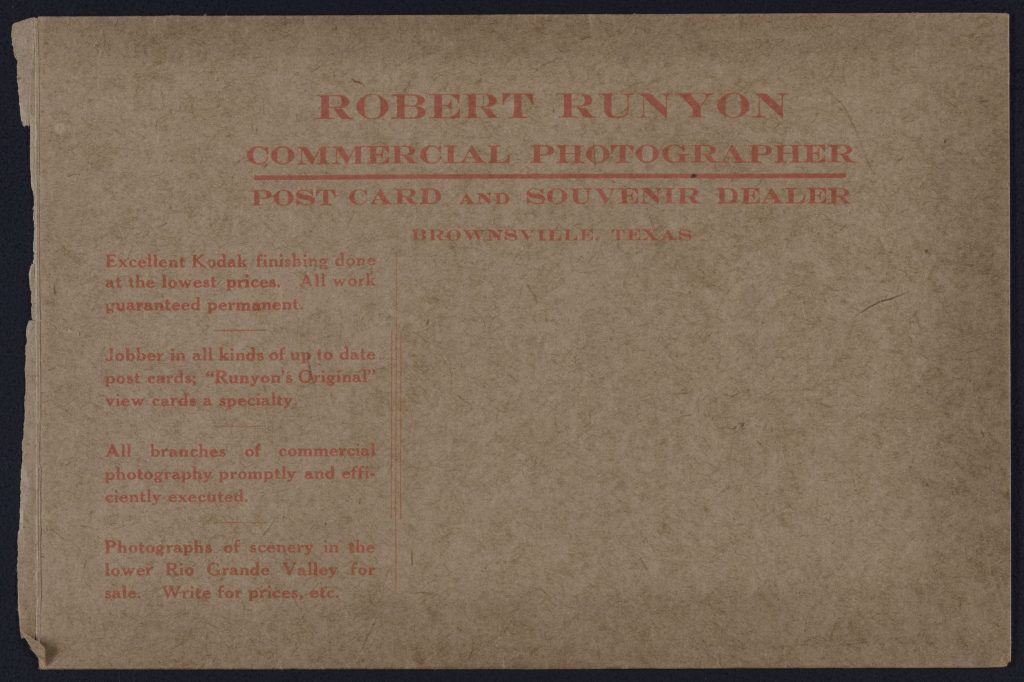

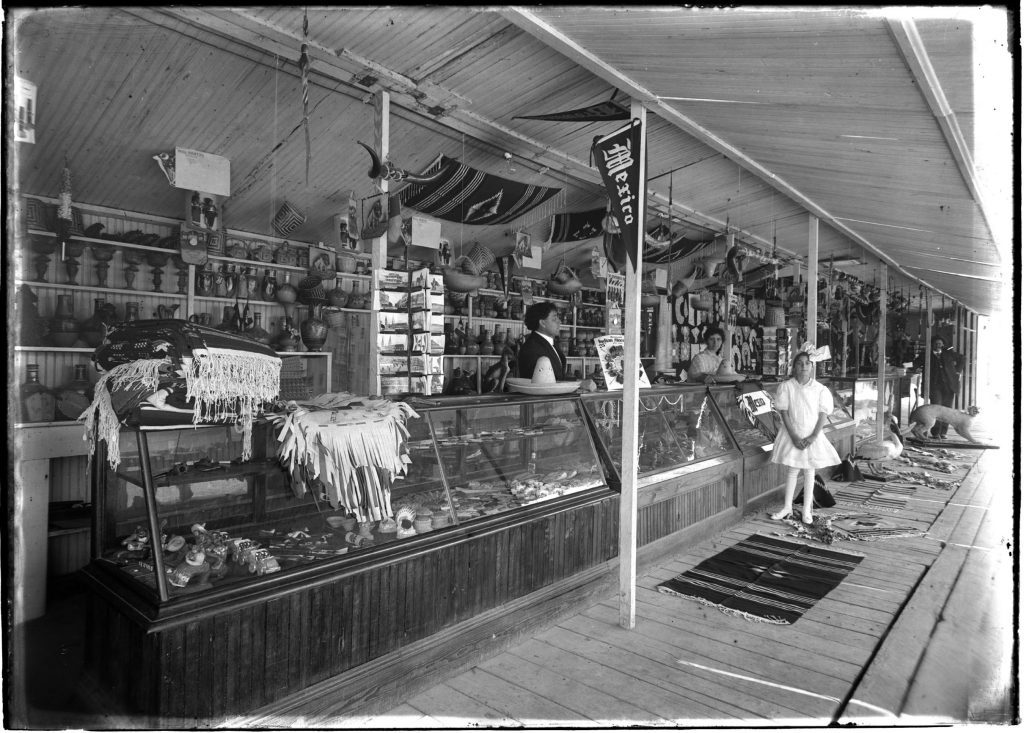

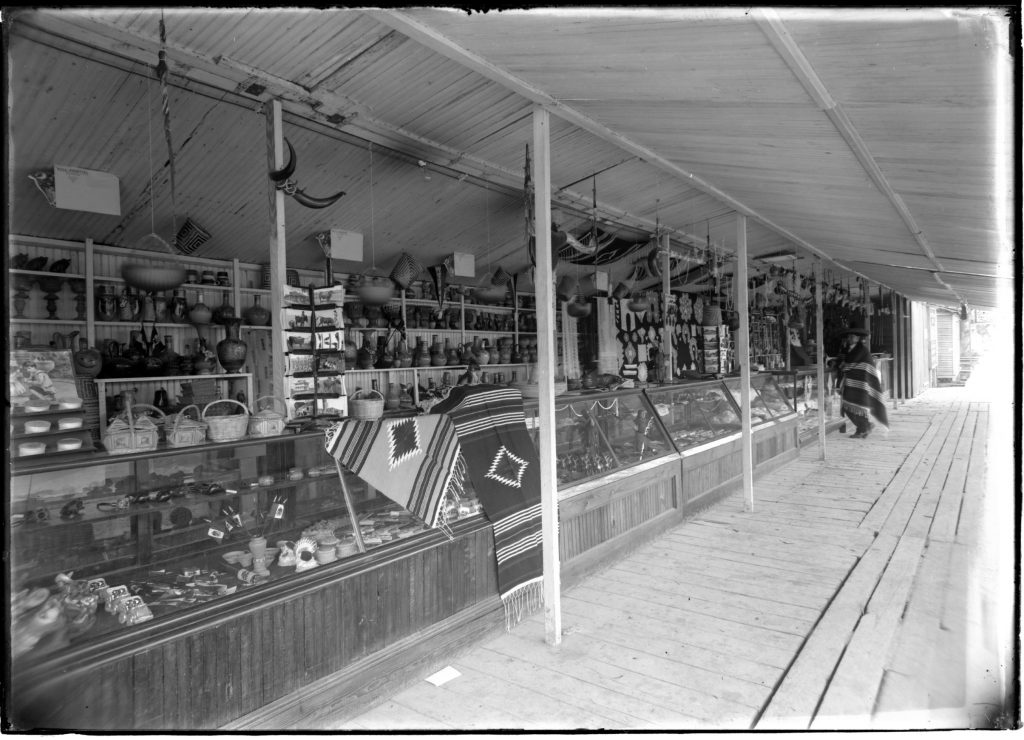

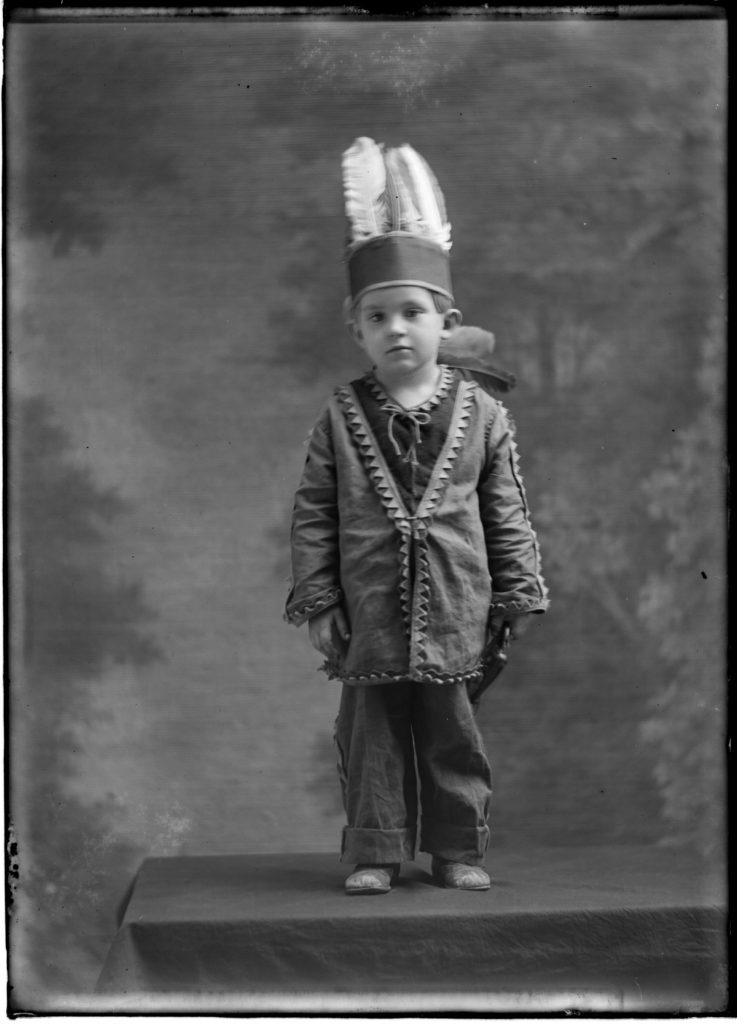

Indeed, despite the focus on his images of combat, of dead Mexican men and children that have garnered his reputation as a photojournalist and war photographer, Runyon knew who and what he was—he identified himself clearly on letterhead, business cards, and correspondence as a “commercial photographer, post card and souvenir dealer.” He was focused and clear about his line of work selling post cards, mementos, and trinkets to tourists and stationed soldiers. In a satisfyingly self-reflective image from 1913, Runyon takes a photo of his own postcards displayed on a shop counter. In the first photo, a child stands in the foreground—staring into the camera, in front of the shop counter. A man with pipe stands in the background, hand on hip, pipe in mouth—a taxidermized stork and wildcat, animal pelts, and rugs at their feet between them. An unidentified man and woman stand separately behind the counter—the man looking away, and the woman looking toward the camera.

In the second image, Runyon clears the scene of all the human figures but one. The man who was last behind the counter is brought forward and leaning in front of the counter. The man is now displaying the goods, costumed in a pancho and sombrero. This pair of images gives an unusually rich representation of how Runyon designed his scenes—rather than capturing a scene. Some woven rugs, taxidermized animals, pelts, and the banner reading “Mexico” are removed (but not the postcard racks!). Here we have two stagings of the scene to compare, as Runyon fashions his pictures for best, most profitable, effect.

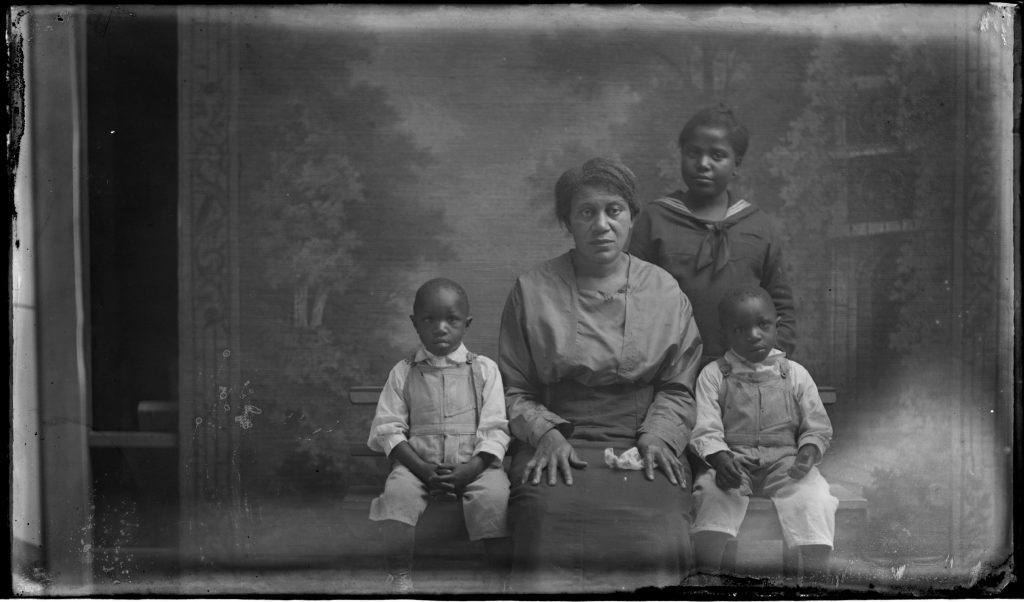

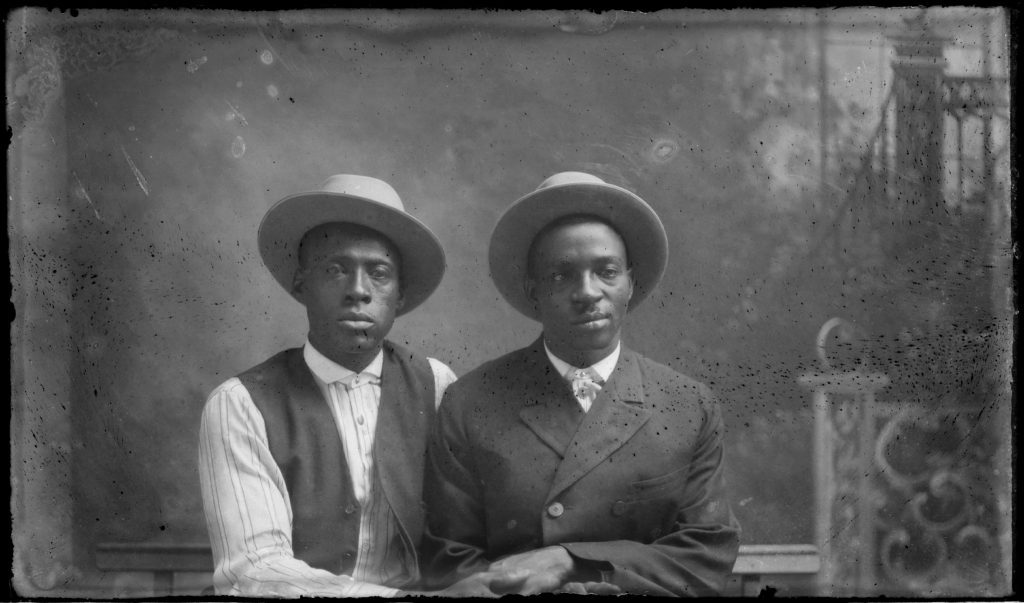

The U.S. military buildup at Fort Brown, which was reopened for the purpose of border enforcement proved advantageous for the commercial photographer. At Fort Brown, Runyon sold postcards, portraits, and even money orders to the troops stationed there from his improvised roadside wooden crate office. The thousands of U.S. soldiers stationed in the area purchased from Runyon, and his foray into portrait photography was lucrative enough to encourage him to open a studio in 1920. [28] The new portraitist purchased backgrounds that he could position indoors or outdoors, and new kinds of camera equipment. He subscribed to Runyon’s portrait photographs from his studio and the Rio Grande Valley area feature 5,663 unique images. Only a fraction of the portraits is of identified subjects, yet we can learn from the posed images that both fulfill and break the conventions of turn of the twentieth century self-fashioning.

Further, we might ask questions about how Runyon solidified a customer base that included African American soldiers and families, Mexicans, Mexican-Americans, and Tejanos, as well as Anglo-Texans and new arrivals—from seemingly a range of different economic classes. Runyon’s studio sign helpfully reads “fotografia” (minus its accent) to indicate a business friendly to Spanish-speakers.

While Runyon advertised the portrait as an aspirational object, Anna Pegler-Gordon argues that the market for portraits was expanded by a developing border state that required face forward photographs for border crossing documents. Pegler-Gordon writes “it is likely that portrait studios gained new business when photographic identity documents were first introduced on the border.”[29] She argues that Runyan’s portraits adhere to many of the conventions of what was required on official documents and points us to Runyan’s own passport picture from 1919, which included his entire family and unless otherwise indicated may strike a contemporary viewer as a family portrait rather than a document for crossing the U.S.-Mexico border.

In addition, missing from the massive portrait collection are another set of revenue-generating portraits—those of Chinese detainees at Fort Brown and other area U.S. Immigration Services detention areas. Runyon was contracted to take three to eight images “of such Chinese or other aliens detained by the Immigration Service.” In his letter to the lead inspector at Brownsville, Runyon outlines his rate for photographing Chinese detainees by the dozen for “the purpose of identification.[30] Runyon’s expansive business model meant Runyon simultaneously profited from taking visa and passport photos that made movement possible for those like his own family, while also recording those captured on the Texas-Mexican border. The single document that tells of Runyon’s involvement with the Immigration Service and outlining his fee is found in a thin folder titled “Kodak Exposure Records, 1907-1911; Receipt Book, 1926-1927; lists of negatives; Miscellaneous Photographic Materials.” Yet, Runyon’s series of images, which he offered to state power, that would mark people as forever foreign and would help to confine their movement in the borderlands are left unrepresented in his photographic archives. His not visible work in support of immigrant detention has thus not marked his legacy.

The massive archival collection at the Briscoe Center for American History allows us to understand Robert Runyon as the commercial photographer he insisted he was. A photographer who responded to requests from specific markets, who constructed visual fields for sale as postcards, portraits, land development advertisements, and government officials. A thoroughly a commercial photographer, Runyon applied for and was granted copyright to eighty-eight of his postcards between 1910 and 1926 and even sued the City of Brownsville when the Chamber of Commerce used his photos in its literature.

The Runyon archives offer the ability to trace his self-taught eye, his trial-and-error equipment purchases, and his filling of orders from several carefully cultivated markets. We are also able to better understand Runyon’s deviation from many of his contemporaries. Runyon’s visual imagination of Texas is marked by his curious lack of interest in tall tales and folklore, the stock and trade of so many of his contemporaries—such as J. Frank Dobie, whose papers are housed at the Harry Ransom Center, and include correspondence with Runyon’s youngest son, Delbert. Runyon was not in the business of campsites and cowboys. Runyon was constructing and capitalizing on a Texas modern—a place of technologically advanced military armaments, utility poles and electric towers, of new construction. This reframing of his work critically invites a studied revisitation of the images of carnage for which he is most recognized. The story of Runyon’s over 14,000 images is the story of demand and supply.

In addition, the available materials leave us with tantalizing questions about his networks of access. We know that Runyon was a transplant to south Texas, adopting and adapting methods and cultivating myriad consumer bases. He solicited work from land developers and government agencies. We can and should delve deeper into the networks provided by his wife and the Medrano family. We know that his profitable images of the Mexican Constitutionalist Army during their campaigns in Victoria and Monterrey were made possible by his brother-in-law, José Medrano who was a member of General Lucio Blanco’s forces. As previously noted, this relationship garnered Runyon special access to revolutionary battles, political executions, and causalities in the aftermath of fighting.[31] Indeed, Runyon was “full of praise for the treatment accorded by the constitutionalists the mule and buggy were furnished by the army. He says he was as given every facility for taking pictures an extended more privileges than he could have expected had he been with an American army.”[32]

The children of Amelia and Robert Runyon lived well into the 2000s and gave interviews to local papers.[33] There is not evidence to suggest that they were asked about their mother or their maternal family’s role in the production of the over 14,000 images. We have yet to learn about the day-to-day efforts of Amelia Runyon—how she helped with the glass negatives, their development, storage, and organizing—or how the networks and capital of an upper middle class Mexican family supported the work known as Robert Runyon’s. Interviews given by the children of Amelia and Robert Runyon in their eighties and their nineties demonstrate how important their family’s long history in south Texas and Matamoros was to them. Their daughter Amali wrote to an interviewer in 2007, “Although I am 91 now and have lost my voice, I am still doing research on my families.”[34] The children of Amelia and Robert Runyon have proudly insisted on the central importance of their family in establishing a photographic narrative of the borderlands. Yet, as they made themselves available to add context to the archives, there’s no evidence of inquiries about their mother’s life, or their extended and closely involved maternal family. It is a heartbreaking lacuna. Indeed, the only trace of Amelia in the boxes of business records and correspondence is a single card of condolence after Robert Runyon’s death.[35] The network and resources provided by Amelia, the Runyon children, and the Medrano family that were foundational to Runyon’s work offer provocative future research pathways. How then to sum up Runyon’s vast body of work? Rather than visual historical truth, we see in Runyon imagery his mercantile ingenuity and perpetual construction, reconstruction and accommodation of visual tropes in the service of commercial viability. He was in the end what he always declared himself to be: a commercial photographer.

Annette M. Rodríguez is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin. Rodríguez concentrates on perennial racist violence in the United States as communicating events that construct and reinforce ideologies and hierarchies of race, gender, citizenship, and national belonging. Her analysis of historical method emphasizes the use of visual texts and is demonstrated in her first book in progress Inventing the Mexican: The Visual Culture of Lynching at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. In addition, Rodríguez has initiated a data, mapping, and social history project on U.S. bounty land grants. This project tracks the over sixty million acres of land granted by both the U.S. federal government and individual states as incentive to serve in the military and as a reward for service. It is provisionally titled Intimate Acquisitions: A Relational History of U.S. Bounty Lands. Rodríguez has taught at Brown University, the Institute of American Indian Arts, Northern New Mexico College, Santa Fe Community College, the University of New Mexico, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

[1] Robert Runyon Photograph Collection, 1907-2008, The Briscoe Center for American History. https://digitalcollections.briscoecenter.org/collection/939 Significant collections of Runyon’s photographs are also housed at the Brownsville Historical Association, the Hidalgo County Historical Museum, the University of Texas Institute of Texan Cultures in San Antonio, and the Central Power and Light Company in Corpus Christi.

[2] War Scare on the Rio Grande was published by The Barker Texas History Center Series in 1992. The series was sponsored by the Texas State Historical Association. (The Eugene C. Barker Texas History Center was renamed the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History in 2008). War Scare, styled similar to a coffee table art book, followed authors Frank Samponaro and Paul J. Vanderwood’s Border Fury: A Picture Postcard Record of Mexico’s Revolution and U.S. War Preparedness, 1910-1917 (University of New Mexico Press, 1988).

[3] According to the series description, there are over 14,000 photographs at the Briscoe Center for American History, with the rest of the collection being a small amount of manuscript material. In descending order of quantity, there are: 69 images from outside the Rio Grande Valley (Washington D.C. and San Antonio are included); 350 Mexican Revolutionary images and “several 1915 Mexican bandit raids”; 681 in Mexico, including scenes in Matamoros, Monterrey, Tampico, and Cuidad Victoria; 927 botanical photos; 2108 images of Fort Brown and the buildup of U.S. military in the lower Rio Grande Valley from 1913 through the end of WWI; 2593 pictures of cities, towns, and agriculture in the lower Rio Grande Valley featuring public and commercial buildings, residences, cemeteries, and special events; and by far the largest category in his photographic output—5,663 posed portraits, most taken at his studio between 1910 and 1926. This data appears in an invaluable resource compiled by Lawrence A. Landis, Claire D. Maxwell, and Nancy K. Taylor, “Series Description,” Robert Runyon Photograph Collection, 1907-1968: A Guide (Eugene C. Barker Texas History center: The Center for American History General Libraries, university of Texas at Austin, 1992), 9-11.

[4] “Runyon Purchases Matamoros Basket Shop; To Remodel,” The Brownsville Herald (Brownsville, Texas), 21 May 1929, pg. 5; “Celebrate Golden Anniversary,” Valley Morning Star (Harlingen, Texas), 4 July 1963, pg. 5.

[5] “Runyon Daughter Spends Life Researching Family Tree,” Valley Morning Star (Harlingen, Texas), 4 January 2007, pg. A23; “Unveiling Mysteries of Brownsville Convent,” The Brownsville Herald (Brownsville, Texas), 1 March 2007, A19.

[6] James Pinkerton, “Runyon’s Photos Capture Rugged History of Rio Grande Valley,” Austin American-Statesman, 25 November 1989, pg. 73.

[7] “Runyon Purchases Matamoros Basket Shop; To Remodel,” The Brownsville Herald (Brownsville, Texas), 21 May 1929, pg. 5; “Celebrate Golden Anniversary,” Valley Morning Star (Harlingen, Texas), 4 July 1963, pg. 5.

[8] Indeed, some of the postcard holders were a personal investment—when Runyon left the Gulf Coast News gift shop, he offered to sell them to the shop. In a letter to Assistant Manager W.H. White, Runyon wrote, “In regards to the small postcard racks, I desire to inform you that these cost me $1.50 per hundred and I have 120 in the lunch room. Do you wish to buy them?” (April 1, 1911). In addition, a who’s-who of turn of the 20th century postcard/postales dealers who supplied the Gulf Coast News gift shop are reflected Runyon’s business records. Some include: the C. I. Williams Photograph Co., Curt Teich & Company, D. E. Abbott & Co., Detroit Publishing Company, The Elite Post Card Co., Inc., McGown-Sulzberger Litho Co., Newfield & Newfield, Inc. Post Card Printers, The North American Post Card Company, and the Williamson-Haffner Company. Robert Runyon Photograph Collection, B1078, folder 1.

[9] Carl S. Chilton, “Robert Runyon: Photographer, Botanist, Politician,” The Brownsville Herald, 14 August 2011, pg. A27.

[10] James Pinkerton, “Runyon’s Photos Capture Rugged History of Rio Grande Valley,” Austin American-Statesman, 25 November 1989, pg. 73.

[11] Robert Runyon Photograph Collection, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, B107, folder 1.

[12] “Carl S. Chilton, “Robert Runyon: Photographer, Botanist, Politician,” The Brownsville Herald, 21 August 2011, pg. A34.

[13] Alicia A. Garza, “Monte Christo, Texas” Handbook of Texas Online http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hvm98. See also: Austin. W. Clyde Norris, “History of Hidalgo County,” Thesis, Texas College of Arts and Industries (1924).

[14] Robert Runyon Photograph Collection, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, B108, folder 1, letter from Melado Land Company dated July 30, 1911.

[15] Robert Runyon Photograph Collection, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, B108, folder 1, letters from Melado Land Company dated November 23, 1911 and November 28, 1911.

[16] Emphasis added. Robert Runyon Photograph Collection, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, B108, folder 1, letters from Melado Land Company dated December 27, 1911.

[18] As noted in an interview with the Runyons’ daughter Amali (granddaughter of Jose T. Medrano), during the 19th century, the cost of attending Seton Hall was approximately $10,000 annually (when adjusted for inflation in 2006). “Valley Boys, Jersey Men: Locals Educated at Seton Hall During Civil War Period,” Valley Morning Star (Harlingen, Texas), 21 December 2006, A23.

[19] James Pinkerton, “Runyon’s Photos Capture Rugged History of Rio Grande Valley,” Austin American-Statesman, 25 November 1989, pg. 73; “Photos Show Mexican Revolution and Life in the Rio Grande Valley,” The Corpus Cristi-Caller Times, 21 June 1991, pg. 70. See also: Frank N. Samponaro and Paul J. Vanderwood, War Scare on the Rio Grande: Robert Runyon’s Photographs of the Border Conflict, 1913-1916.

[20] James Pinkerton, “Runyon’s Photos Capture Rugged History of Rio Grande Valley,” Austin American-Statesman, 25 November 1989, pg. 73.

[21] Martha A. Sandweiss, Print the Legend: Photography and the American West (Yale University Press, 2002), 39.

[22] See RUN00096-00098, 00099, 00100-00107, and 00157. The Briscoe Center for American History. Runyon, Robert, photograph collection.

[23] Monica Muñoz Martinez, The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas (Harvard University Press, 2018), 236-240.

[24] Sandweiss, 40.

[25] Important works that focus on the violent images from 1910-1916 include Robert Runyon: Fotografo de la revolución Mexicana en la frontera by Francisco Ramos Aguirre (Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas: 2009) and War Scare on the Rio Grande: Robert Runyon’s Photographs of the Border Conflict, 1913–1916 by F. N. Samponaro and P. L. Vanderwood (Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1992).

[26] Sandweiss, 59-60.

[27] Martinez, 232.

[28] “Robert Runyon, New Cameron County Democratic Chairman, Opposes Bolters,” The Brownsville Herald, 29 July 1948, pg. 13. “Carl Chilton, “Robert Runyon: Photographer, Political Activist, and Botanist,” The Brownsville Herald 22 October 2017, pg. C3. “Runyon,” The Brownsville Herald, 21 August 2011, pg. A34.

[29] Anna Pegler-Gordon, Insight of America: Photography and the Development of U.S. Immigration Policy (Berkeley: UC Press, 2009), 186-187. I appreciate my colleague Madeline Y. Hsu’s remainder of Pegler-Gordon’s work and the crucial relationship between the development of the U.S. immigration apparatus and the production of visual “racial” difference.

[30] Robert Runyon Photograph Collection, Briscoe Center for American History, B108, folder 8.

[31] Cavazos, Julian Cavzos, “Local Photographer, Historian Robert Runyon’s Legacy Captured on Film,” The Brownsville Herald, 8 August 2006.

[32] Gordon Shearer, “Brownsville Boy Travels With Rebel Army Picturing Battles: Robert Runyon Is Furnished Mule and Buggy by Constitutionalists,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram (Fort Worth, Texas), 4 May 1914, pg. 5.

[33] Cavazos, Julian Cavazos, “Local Photographer, Historian Robert Runyon’s Legacy Captured on Film,” The Brownsville Herald, 8 August 2006. Victoria Manning, “Digging Deep: Runyon Daughter Spends Life Researching Family Tree,” The Brownsville Herald, 3 January 2007. In addition, a Runyon family member helped to properly identify individuals in several archival photographs in June 2019. For example, see description, “Mrs. Arturo Gonzalez (Felipa M. Gonzalez) and her niece, Virginia Runyon (Gilbert) at Palm Grove, ca. 1918,” RUN04805 The Briscoe Center for American History. Runyon, Robert, photograph collection https://digitalcollections.briscoecenter.org/item/142840

[34] Victoria Manning, “Digging Deep: Runyon Daughter Spends Life Researching Family Tree,” The Brownsville Herald, 3 January 2007.

[35] Robert Runyon Photograph Collection, Briscoe Center for American History, B107, folder 1.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.