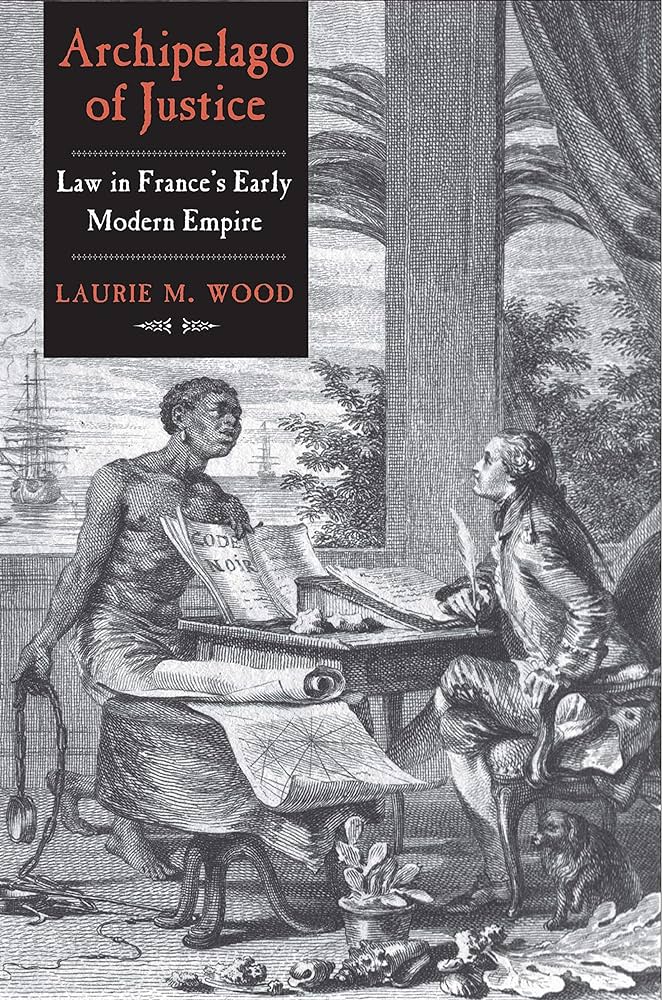

Laurie M. Wood was one of the foremost early modern global historians of her generation and a remarkable friend and colleague. Her first book, Archipelago of Justice: Law in France’s Early Modern Empire, won the 2021 Boucher Prize from the Society of French Colonial History. The committee lauded her integrated framing of the Caribbean and Indian Ocean worlds as “a remarkable accomplishment … a powerful and creative intervention” made possible by “astonishing archival tenacity” and “beautiful writing.” They highlighted her use of stories of the powerful and marginalized to show how they created “power, order and the very nature of French colonialism.” The commendation astutely encapsulated all the qualities that made Laurie’s work so outstanding and impactful. She was one of the leaders of a new research approach that saw all the regions of the first French empire as inextricably linked.

Laurie was a native Texan who was proud that every educational institution she was part of was public. She grew up in Abilene, graduated summa cum laude as a History major from Texas Tech, and earned her PhD at the University of Texas at Austin. Her horizons of all kinds expanded quickly far beyond the Texas Panhandle but she remained devoted to Texas food (serving barbecue for the many out of state visitors to her wedding in Abilene, and delighting in eating queso, chips, salsa and tamales on a trip back with her family last Thanksgiving), to the faith she grew up with, and to watching football as a holiday ritual. An alchemical year as a UW Law & Society Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Wisconsin-Madison profoundly shaped Laurie’s professional and personal life. In nine months in Madison, she framed her book project, secured a tenure-track job at Florida State University, and met her partner, Cale Weatherly.

Soft-spoken and kind, Laurie was a no-nonsense intellectual powerhouse who thrived under pressure. Her work was always profoundly collaborative, and she generously exchanged research, writing, and ideas with many peers. Unfailingly thoughtful and supportive, her straightforward pep talks, warm sense of humor, and incisive feedback made her an ideal scholarly interlocutor – and more than that, a true friend who was always there to talk through setbacks and celebrate successes, both personal and professional. She brought her trademark combination of energetic enthusiasm, seriousness of purpose, and historiographic acumen to her collaborative projects, which included one on everyday materials of colonial legal spaces and another on the multiple meanings of a botanical expedition in French Guyane, to be completed by her co-author. She told one coauthor her goal was to make their work “maximally helpful” to fellow scholars, which was a very Laurie approach to historiography.

Laurie’s research track was jump started early in her PhD program by the generosity of John Garrigus, who shared his archival photographs of notarial documents made in Saint Domingue in the early 1790s for a first-year research paper. Laurie was fascinated by the questions of the broader French world – its legal process, its varied set of actors, its geographical immensity and its extraordinary archival records. As she framed her dissertation and then her book, she integrated these themes as the core of her research agenda. In her reading (she was the first UT student who had ever taken four graduate historiography courses – in colonial Latin American, early American, and African as well as early modern European history) and in her sharing work in writing and conversation with the UT’s early modern history group and others, she came to recognize the essential role of the Indian Ocean, and centered the problematic as a global, not simply Atlantic, one.

Yet even as her work expanded geographically, it remained grounded in the stories of the individual people who made France’s empire. This very human scale reflected a core methodological priority of Laurie’s: to think about and work to see the past from the perspective of historical actors. As she explained in an interview about Archipelago of Justice, she didn’t want to just look at the big picture of France’s empire but to grapple instead with “the very localized question of what happens when … you’re trying to imagine the French empire that rules your life in really tangible ways but is also really hard to wrap your mind around.” The twin priorities of thinking globally and locally drove much of Laurie’s research agenda.

At Florida State, Laurie quickly became a dedicated and creative professor. Bubbling over with ideas to help the department, she lit up any meeting with characteristic insight and ruthless practicality. Her innovative and popular courses often dealt with parts of the world students are unfamiliar with. She was as committed to students who would go on to important but ordinary occupations as she was to academic stars, always making her classes accessible to a wide range of undergraduates. She strongly believed that confronting historical truths could have a lasting trickle-down effect that her students would take with them into many parts of their lives. From the moment she walked in the door, she also turned her determination to be “maximally helpful” toward the graduate students. In addition to leading a wide range of seminars and broadly training early modern scholars, she also coached them through grant proposals and interviews and all the skills of being a professional historian that graduate school seldom actually teaches. She knew how hard the work was, and she wanted people to go into it with their eyes open and with the best skills and tools she could provide them.

Staying true to her research priorities, Laurie developed her second book project, Flickering Fortunes: Women, Catastrophe & Complicity in the French Tropics, with lightning speed. With the support of the Shelby Cullom Davis Center at Princeton, the Hagley Library, and the Library Company of Philadelphia, Flickering Fortunes focused on the female “foot soldiers” of the eighteenth-century French empire in what would have been a major historiographic intervention. Drawing on material from her extraordinary archival database, Laurie envisioned arguing how even though women were often left behind in port cities, they had a significant role to play in building, managing, and upholding slavery and global capitalist systems.

Laurie’s synergistic approach to research and teaching was driven by her enthusiasm for all aspects of her work. As any of Laurie’s colleagues can testify, her passion for early modern history was endless and infectious. Perhaps nothing better testifies to her intellectual energy than the fact that, through two years of intensive treatment for aggressive breast cancer before her death aged 38, she continued to find joy and meaning in her research and teaching. She also sustained her connections with students and colleagues. She leaves her two young children, her husband, their families, and a wide circle of friends. She loved them so much and she loved everything about being a professor.

A fund has been established at Florida State in Laurie’s honor to support the undergraduate community she cared about so much and at Penn where she received her care. This fund is designed to support research into the subtype of breast cancer (mTNBC) that Laurie had. mTNBC is the most deadly, the least understood and the most lacking in targeted treatments.

Julie Hardwick, University of Texas at Austin

Meghan Roberts, Bowdoin College