Getúlio Vargas, President of Brazil from 1930-1945, is often credited as the champion of the Brazilian working class during the twentieth century. His policies led to the progressive industrialization of Brazil and to a barrage of labor regulations that protected workers’ rights. However, not everyone benefited equally from these laws. Thousands of poor Cariocas (Rio de Janeiro’s residents) who labored outside the formal economy were not legally considered workers and faced great challenges to attain the rights that Vargas originally intended for the organized working class.

Brodwyn Fischer presents a compelling study integrating urbanization, patronage networks, and conceptions of citizenship in modern Brazil. The book addresses the formation of poor people’s rights in Rio de Janeiro between 1920 and 1960. The basic thesis is that the poor’s claims to economic, social, and political rights were constantly constrained by legal ambiguity and informality, fostering a state of partial but perpetual disenfranchisement. Despite the unprecedented expansion of labor benefits for the workers during the Vargas era, socioeconomic assumptions and bureaucratic hurdles revealed the discrepancy between legislation and social realities. New regulations prevented outright exclusion from rights, but legal ambiguity prevented their full attainment, placing a significant portion of urban poor’s lives outside the sphere of citizenship. Fischer shows how this contest over citizenship rights played out in urban spaces, courtrooms, and in the government bureaucracy.

The implementation of legislation on urban growth in Rio in the early twentieth century shows one such disparity in the ways the poor were both included and excluded from citizenship rights. The sanitary code of 1901 and especially the Building Code of 1903 had lasting impacts on the conceptualization of urban spaces and poor’s place in cities. Both sets of legislation targeted the favelas (informal settlements) for removal, associating them with disease and moral danger. However, the incapacity of the state to enforce those laws enabled tolerance for them and created a venue for the poor to achieve a tenuous hold on land in the city.

Getúlio Vargas’ ascension to the presidency put the poor at the center of his populist project. A network of patronage among politicians, middlemen, and poor residents in the favelas soon arose to defend vulnerable constituents against the laws’ enforcement and to guarantee political support. Vested interests in the slums would prolong their existence in an atmosphere of legal uncertainty. While becoming the only solution to Rio’s housing crisis, favelas remained illegal according to the law. This fact deprived residents of any meaningful claim to urban rights, making vulnerability and dependence a key feature of Rio de Janeiro’s poverty.

Vargas also extended considerable material benefits to the Brazilian working classes mainly through the Consolidation of the Labor Laws of 1943. In the process, a poverty of rights emerged that made workers supplicants rather than fully enfranchised citizens. These reforms were exalted more as public displays of generosity from the president than as the attainment of full rights belonging to the citizens. Vargas’ administration articulated a conception of citizenship underpinned by notions of work, family, and patriotism according to which rights were distributed. In order to access these rights, the poor had to negotiate not only discourses of citizenship in their written petitions to the government, they also needed documentation to claim their benefits. The possession of birth certificates, work ID’s and other bureaucratic hurdles created a multi-tier system in which the procurement of a specific document unlocked the next level of social protections. The precondition of documentation for citizenship turned rights into privileges that benefited only those among the poor who were documented. Political loyalty, bureaucratic agility, and corruption often meant the difference between exclusion or access to benefits.

If Brazilian bureaucracy created serious obstacles for the attainment of rights, courtrooms presented a legal mine field awaiting favela residents. The inconsistent and heterogeneous Brazilian legal system added more ambiguity to the situation of the undocumented poor. Legal decisions often rested on perceptions of individual circumstances and character and as such, poor Brazilians and judicial officials engaged in negotiations of judicial responsibility and sentencing based on open-ended ideas of civic worthiness. Documentation might provide a solid signifier of citizenship permitting Rio’s residents to escape the more nebulous dimensions of social character, class, and circumstance. A positive vida pregressa (brief life history) and the possession of other documents such as a work card, constituted less ambiguous signs of civic honor. Thus, poor people who could not present themselves as such saw their civic rights undermined and a higher risk of conviction in the courts.

Fischer concludes by chronicling a series of conflicts in the favelas that were due to the growth of the city and the rising value of land in the 1950s and early 1960s. The proliferation of local social movements to defend claims to abandoned lands, coupled with networks of support from leftist politicians and favela middlemen, succeeded in preventing most of the public and private evictions in this period. However, this success rested on political loyalty and not in the enfranchisement of their residents per se. Untitled permanence and illegality would continue to constitute the ultimate legacy of the community’s legal battles.

Fischer offers a well-researched and nuanced analysis of ambiguities of citizenship in modern Rio de Janeiro based on the eclectic use of civil and criminal court cases, legal codes, statistics, oral histories and even samba lyrics.

You May Also Like:

Confederados: Texans of Brazil by Nakia Parker

Partners in Conflict: The Politics of Gender, Sexuality, and Labor in the Chilean Agrarian Reform, 1950-1973

Also by Marcus Oliver Golding:

Precarious Paths to Freedom: The United States, Venezuela, and the Latin American Cold War

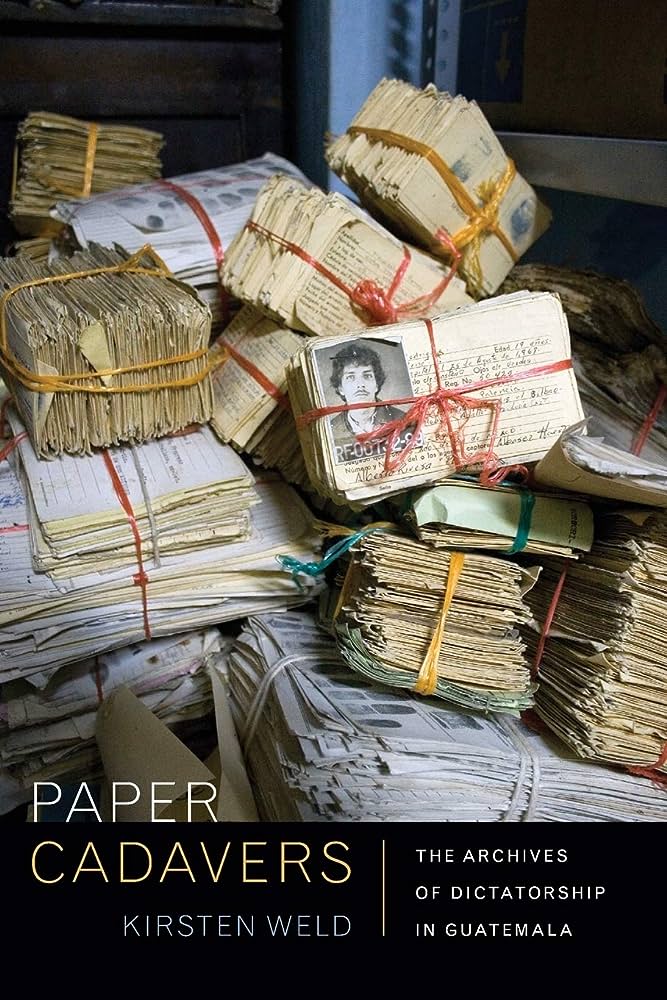

Paper Cadavers: The Archive of Guatemalan Dictatorship