The Climate in Context Conference took place on April 22 & 23, 2021. To view recordings of sessions, visit our virtual conference page.

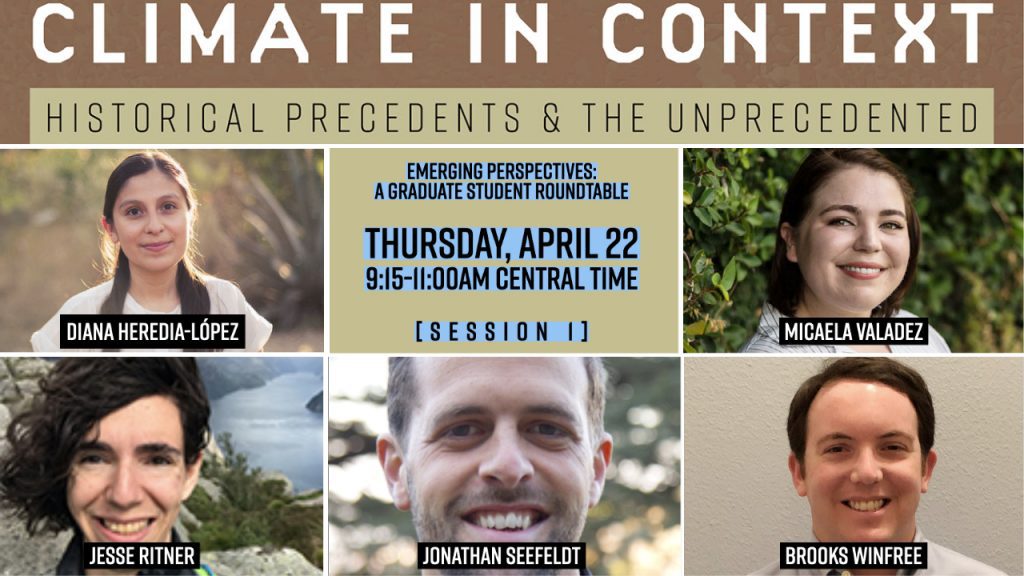

Session I: Emerging Perspectives: A Graduate Student Roundtable

The first panel of the conference was a roundtable composed of five graduate students from the University of Texas at Austin’s History Department. Although temporally and geographically diverse in their areas of focus, each panelist engaged with environmental issues in their research. For each of their presentations, they were tasked with discussing how climate change intersects with their own work.

In his presentation, “An Upwelling of Stone: Climate Change and Infrastructure Agendas in Early Modern India,” Jonathan Seefeldt discussed Rajsamand, a large-scale precolonial dam in the present-day western Indian state of Rajasthan built between 1662 to 1676 AD. Using Rajsamand, Seefeldt problematized the broadly-conceived notion that these massive infrastructure projects were projections of kingly power by highlighting that the dam’s construction was less a prestige project than a response to failed monsoons, unusual regional aridity, and mounting social strain.

Diana Heredia-López’s presentation, “Cultivating Parasitism: Early Modern Insect Crops and the Limits of Commodification,” advocated for the need to investigate the different manifestations of parasitism throughout the Plantationocene and the non-linear trajectories of plantation agriculture by exploring the seventeenth-century project to scale-up the production of cochineal in the Yucatan Peninsula.

Jesse Ritner’s paper, “Skiing in Variable Conditions: Climate Adaptation, Profitability, and Repercussions,” examined how modern ski resorts used highly profitable snow-making technologies to adapt to variable climatic conditions that caused inconsistent or insufficient snowfall for ski resorts. Through the creation of consistent snowfall, these technologies were supposed to make skiing more accessible, but the reliance on artificial snow production ultimately exacerbated disparities within the ski industry.

In “Drafting Blueprints: Critiquing the Past to Fight Climate Injustice Today,” Micaela Valadez’s presentation explored the history of Communities Organized for Public Service (COPS) in San Antonio, Texas, to critique the historiography of the organization as being unbalanced and not contending with the organization’s decision to not use the rhetoric of race or class when agitating for change. In doing so, she argued that if historians are to help in the current climate justice movement, they need to divert their attention to understanding how communities of color fight against environmental and climate injustice.

Brooks Winfree’s talk, “African Americans, Slavery, and the Long History of Environmental Degradation in the Cotton South,” advocated for historians to consider slavery and enslaved people’s interest in forging alternative understandings of the land by considering how the cotton-based plantation zone of the nineteenth-century Gulf South became a contested site of competing ideas of environmental use.

Dr. Mary Mendoza from Pennsylvania State University provided commentary on the five presentations. She commended the historians for considering a wide range of issues in the complex relationships between people and the environment in the context of climate change. She pressed each of the presenters to dig deeper into how diverse peoples adapted to and responded to changing environments and climates. Dr. Mendoza also stressed the importance of looking at how environments mediate relationships between people as they compete for natural resources.

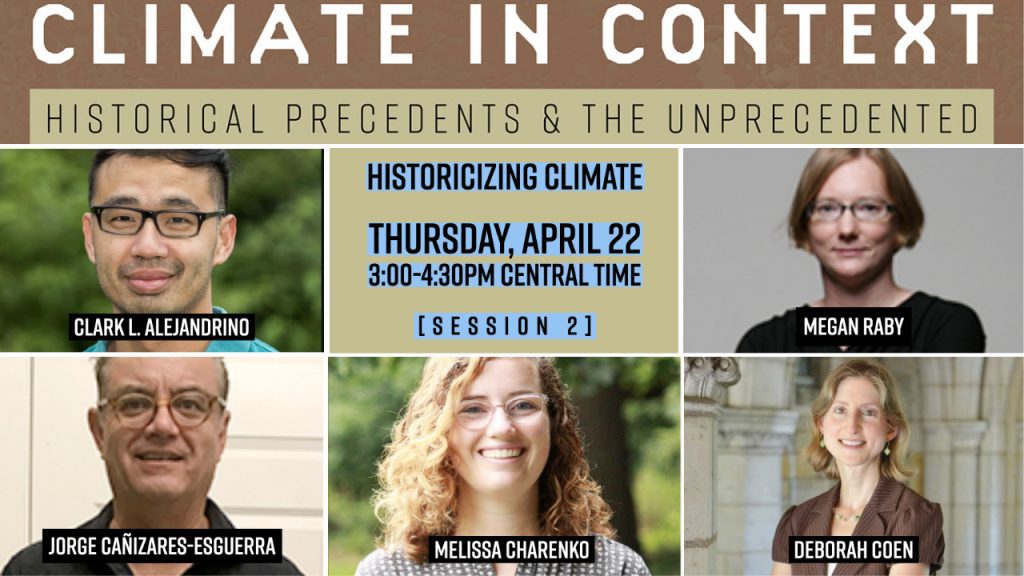

Session II: Historicizing Climate

In the second session of the conference, four scholars examined the historical ways of knowing climate in temporally and geographically different contexts. Dr. Clark L. Alejandrino’s presentation, “Beyond Numbers: Knowing Typhoons in Late Imperial China,” argued against the fetish for numbers that dominates the study of past storms and, to some extent, historical climatology. He argued that historians need to take seriously the diverse, non-numeric ways that people along the southern coast of China recognized, understood, and conceived typhoons in the past.

Dr. Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra’s talk, “The Anthropocene and Epistemological Colonialism: The 18th-Century Spanish American Origins of Humboldt’s Global Histories of the Earth and Climate Change,” critiqued the historiography of Alexander von Humboldt and his role in creating the intellectual genealogies of the Anthropocene. While Humboldt played an important role in spreading environmentalism throughout North America and Europe, he largely erased both the physical and intellectual communities he interacted with in Latin America.

In “Measuring by Proxy,” Dr. Melissa Charenko explored how scientists’ use of climate proxies, preserved physical characteristics of past climates that stand in for direct meteorological measurements, constrained and compelled what they thought about climate’s past and future. She focused on predictions derived from tree rings in the 1920s and the predictive limitations of pollen analysis in the 1980s given the unprecedented future of global climate change.

Dr. Deborah Coen’s presentation, “Degrees of Vulnerability: Why We Need a Feminist History of Climate Science,” discussed the discourse surrounding the diverse concepts of human vulnerability that has developed since the 1970s and hypothesized that this evolving discourse reveals the influence of the global feminist movement in the 1980s and 1990s. She advocates that a history of the science of climate vulnerability should attend to the presence of this past, the living legacy of two centuries of efforts to separate the knowing human subject from the human object of geophysical influence.

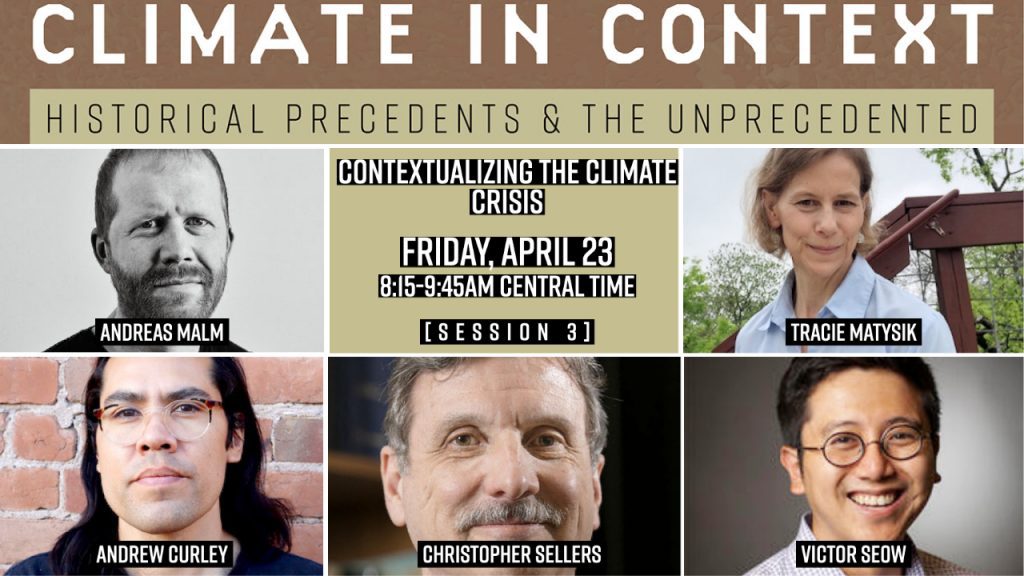

Session III: Contextualizing the Climate Crisis

In the third session of the conference, the invited scholars analyzed the causes and consequences of the climate crisis with a focus on the intimate connections between fossil fuels, race, colonialism, and capitalism. Dr. Christopher Sellers’s talk, entitled “Gathering Clouds over Petropolis: A Prolegomena,” focused on a single historical thread within the anthropogenesis of climate change: the oil industry. Centered on two locales, the eastern coast of Texas around Houston and the southern coast of Veracruz in Mexico, Sellers offered more local and human scales of historical action that explored how corporations, governments, and other institutions created and sustained the material conduits that have provided for the world’s growing petroleum needs over the last century.

In Dr. Andreas Malm’s presentation, he discussed the book White Skin, Black Fuel: On the Danger of Fossil Fascism that he co-authored with the Zetkin Collective. The book is the first study that critically engages with the far right’s role in the current climate crisis and how fossil-fueled technologies were born steeped in racism. The racist legacy of fossil fuels has led to the far-right’s defense of the fossil fuel industry and their anti-climate change policies.

Dr. Andrew Curley’s talk, “The Cene Scene: Modernization Myths, Navajo Coal Development, and the Making of Arizona,” Curley scrutinized the “cene” narratives of writing history within larger geological frameworks and stressed the importance of Indigenous understandings of temporality in relation to water resources in the American Southwest. When considering the “cenes,” we must ask what future is enabled for indigenous people when we understand all of time through these broad geological and geopolitical lenses. One of his main points was that the metrics and theorizations of our current geological era must account for the struggles of Black and Indigenous peoples, and there must be space for demands for decolonization and abolition in climate debates.

Dr. Victor Seow, in his presentation, “States of Second Nature,” examined the interrelationship between the state and nature. The role of the state, while not ignored in studies of climate, is often pushed to the background. Seow argued that modern states play an active role in engendering environmental change and that we need to extend our inquiries beyond the capitalist systems that are often the points of focus. He ended with a discussion of turning toward a statist solution to the climate crisis, a crisis that modern states were complicit in.

Session IV: Practicing What We Preach: A Roundtable

In the fourth session of the conference, five scholars presented their ideas on how the historical profession, and academia in general, can be more responsive to the climate crisis. Dr. Andrea Gaynor’s presentation, “We Use the Living Earth to Make Our Histories,” argued that historians often engage in disavowing the problems of climate change and our contribution to them in the course of our historical work. She advocated that historians have important roles to play through modifying how we conduct our professional work and acting to modify the institutional and wider social frameworks that we operate within. She followed up with concrete suggestions that included the digitization of archives to reduce research travel and hosting low-carbon conferences through virtual participation and catering choices.

Dr. J. T. Roane’s talk, “Rural Black Social Life in the Chesapeake After the 1933 Great Hurricane,” Roane explored the strong relationship between Black communities and waterscapes in the Tidewater region of Virginia. With the onset of industrialization in the nineteenth century, Black people were increasingly excluded from the waterscapes that played such vital roles to Black communities.

In “Louisiana: Race, Justice, and the Ecological Legacies of the Plantation Economy,” Dr. Justin Hosbey illustrated how the humanitarian crisis triggered by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 exposed the racial violence and class domination that structures New Orleans and the broader American South. He analyzed how the politics of space, place, and class in Black New Orleans has been transformed by post-Katrina redevelopment policies and that these reconstruction projects can be read as anti-Black spatial tactics.

Dr. Paul N. Edwards’ presentation, “Writing History into the Sixth IPCC Assessment Report,” discussed his work as one of the few social scientists working on the sixth Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Assessment Report and the challenges of integrating historical research into the IPCC Assessment Report.

Dr. Dolly Jørgensen’s talk, “Isn’t all Environmental Humanities ‘Environmental Humanities in Practice’?,” followed Edwards’ and chronicled how after she and Dr. Franklin Ginn took over as co-editors of the Environmental Humanities journal in January 2020 they worked to make the journal more inclusive of environmental humanities practices. As part of this effort, they introduced a new category of journal article, “Environmental Humanities in Practice,” and examined the tension in this decision to develop a separate category of scholarship geared toward outreach.

Session V: Going Public with Climate History: A Roundtable

In the conference’s fifth session, five scholars considered the public-facing aspects of their work and how work about climate history, climate change, and environmental humanities gets translated to the public. Dr. D. O. McCullough’s talk, “Specific Constraints for a Universal Challenge: Navigating Resources and Space to Create a History of Climate Science Exhibition,” illustrated the challenges and possibilities of using museum exhibits to communicate the history of climate science and offered several suggestions for so effectively. He advocated for curators of history of climate science exhibitions to draw their narratives from the objects available for display, to treat their own institutions as artifacts to model critical reflection about past practices in meteorology and climate, and to foreground museum space and audience in the design process.

Dr. Bethany Wiggin’s presentation, “When Will It Be Over? Water, Flood, Toxics, and the Duration of Colonial Legacies in Philadelphia,” explored climate impacts as ongoing colonial relations and explored the coloniality of climate change through a series of interrelated public humanities projects developed in Philadelphia amidst flash floods, refinery explosions, and school children’s hopes and dreams for Philadelphia in 2100.

In Dr. Prasannan Parthasarathi’s talk, “Indian Ocean Current,” he discussed the “Indian Ocean Current: Six Artistic Narratives,” an exhibit at Boston College’s McMullen Museum of Art that he co-curated with Salim Currimjee. The exhibit integrated material on climate change, ocean science, and the crisis of fisheries with perspectives from six contemporary artists from around the western Indian Ocean World.

Dr. Tom Chandler and Dr. Adam Clulow’s presentation, “Modeling Virtual Angkor: An Evolutionary Approach to a Single Urban Space,” spoke about how the Virtual Angkor Project aims to recreate the sprawling Cambodian metropolis of Angkor, the largest settlement complex of the preindustrial world, at the height of the Khmer Empire’s power and influence in Southeast Asia. They highlighted the long development of the project, the challenges involved in modelling the historical environment, and the question of climate variability and the decline of Angkor.

Raymond Hyser is a third-year Ph.D. student in the History Department. His research interests include the intertwining histories of science, agriculture, and the environment in trans-imperial spaces, particularly within the British Empire, during the nineteenth century. He also has a growing interest in world history and digital humanities. His current research traces the agricultural knowledge networks of coffee cultivation between the West Indies and South Asia during the long nineteenth century.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

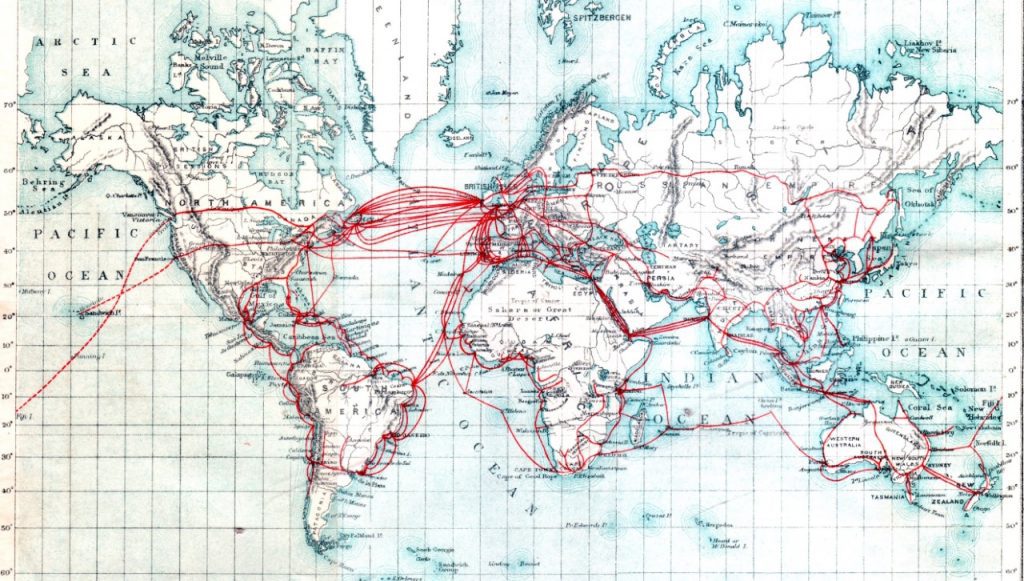

![The abuelas [grandmothers] of Sepur Zarco. First row seated (from right-left): Antonia Choc (blue huipil); Felisa Cuc (orange huipil); Rosario Xo (blue huipil); Candelaria Maaz (pink huipil); Manuela Bá (light blue huipil); Demesia Yat (dark blue huipil);

Seated behind Demesia Yat (left) (wearing white huipil with green embroidery): Margarita Chub.

Standing, second row, (from right-left): Matilde Sub (pink); Catarina Caal (off-white); María Bá (purple huipil); Cecelia Xo (purple huipil); Carmen Xol (tan flowered huipil)](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/45385291432_f7d10bb473_k-1024x683.jpg)