Para llegar a un público más amplio, volvemos a publicar en español el artículo de Lucero Estrella, Memories of War: Japanese Borderlands Experiences during WWII. Le agradecemos a Lucero por la traducción.

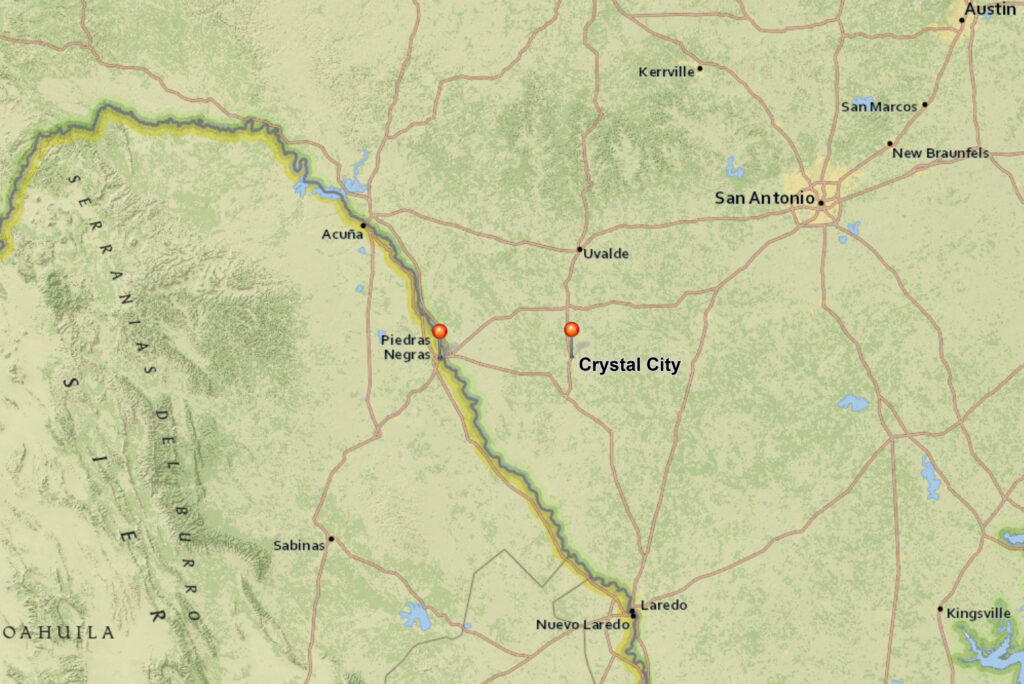

Cuando visité el hogar de Rosy Galván Yamanaka en Piedras Negras, Coahuila, me tenía preparado un plato de udon al estilo mexicano. Me senté en su comedor y escuché mientras me contaba historias de su abuelo, José Ángel Yamanaka, un migrante japonés que llegó a México a principios del siglo XX. Como muchos otros inmigrantes japoneses, Yamanaka llegó para trabajar en las minas de carbón en Coahuila. Eventualmente se quedó a vivir en Piedras Negras. Esta ciudad fronteriza no es solo un lugar con una comunidad de mexicanos con ascendencia japonesa, sino que también es una ciudad fronteriza donde actualmente están llegando grupos de migrantes hondureños, venezolanos y entre otros. Aunque no parezca evidente, las historias ignoradas de las comunidades japonesas en México y Texas durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial y los relatos de los migrantes en la frontera en el presente resaltan experiencias de exclusión, criminalización y violencia que son similares.

Después de acordarse que tenía algunas fotografías de su familia de 1942 a 1945, Galván Yamanaka empezó a contarme cómo su abuelo se había mudado a Monclova, Coahuila, durante la guerra. Su abuelo se había mudado al sur de la frontera, después de que el presidente mexicano Manuel Ávila Camacho ordeno que todos los japoneses que vivían cerca de la frontera se tenían que trasladar a la Ciudad de México y Guadalajara. La familia Yamanaka estuvo separada durante tres años, pero tuvieron la suerte de permanecer en el mismo estado. Otras familias mexicanas de origen japonesas no pudieron visitar a sus familiares debido a los costos y las largas distancias. Galván Yamanaka sabe que su abuelo se vio obligado a dejar Piedras Negras y trasladarse a Monclova durante la guerra porque ella nació en 1941, al inicio de la guerra. Ella tiene estas historias de los años de la guerra debido al tiempo que pasó con su abuelo y sus familiares mayores y cree que es su deber compartirlas con las generaciones más jóvenes de su familia.

Los recuerdos de los mexicanos de origen japones de la Segunda Guerra Mundial permanecen ocultos. Algunas familias no saben qué les pasó a sus familiares japoneses durante la guerra. Muchos tardaron años antes de descubrir por qué el Estado mexicano separó forzosamente a sus parientes japoneses sin que importara su ciudadanía. Estos recuerdos de la guerra quedan dentro de cada familia mexicana japonesa. Algunas familias mexicanas con ascendencia japonesa desconocen la discriminación que enfrentaron sus familiares y que muchos fueron obligados a abandonar sus hogares. De hecho, la mayoría de los mexicanos desconocen este momento de la historia mexicana.

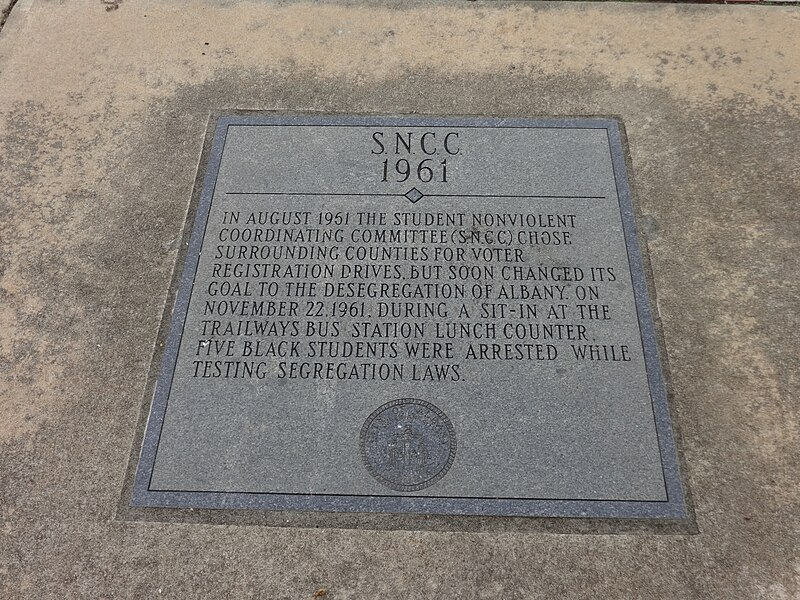

En enero de 1942, el presidente Ávila Camacho ordenó a todos los inmigrantes japoneses y las comunidades japonesas que residían en a la costa del Pacífico y cerca la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México se trasladaran al centro de México. El gobierno mexicano les dio un aviso de 24 horas para evacuar durante la primer orden y les pidió trasladarse a Guadalajara y Ciudad de México. El gobierno también dejó de aceptar solicitudes de naturalización de inmigrantes japoneses e impidió que los japoneses recaudaran fondos de sus cuentas bancarias o realizaran cambios de dinero.[1] La respuesta del gobierno al ataque a Pearl Harbor de diciembre de 1941 se centró en las comunidades japonesas cercanas a la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México y en la costa del Pacífico, ya que estas comunidades fueron marcadas como una “amenaza” tanto para Estados Unidos como para México.[2] Los japoneses fueron responsables de organizar sus propios viajes al centro de México e informar su reubicación y domicilio al gobierno. A diferencia de algunos países de Latinoamérica, el gobierno mexicano no trabajó con el gobierno de estadounidense para deportar a sus comunidades japonesas a campos en Estados Unidos.[3]

Las historias del encarcelamiento de japoneses en Estados Unidos y la expulsión forzada de japoneses en México suelen no ser contadas juntas, ocultando la manera en cual el gobierno mexicano y el gobierno estadounidense fueron cómplices en la racialización y criminalización de las comunidades japonesas durante la guerra.[4] Al contar historias transfronterizas de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, aprendemos que las agencias de inteligencia mexicanas, junto con el FBI, la Patrulla Fronteriza, el Servicio de Inmigración y Naturalización (INS) y las autoridades locales en la frontera entre México y Texas, fueron parte de la reubicación, expulsión y vigilancia de ciudadanos japoneses y familias japonesas de la región fronteriza. Estas narrativas no sólo incluyen a el norte de México y Texas en las historias de exclusión y vigilancia japonesa durante el comienzo del siglo XX, sino que también ilustran cómo las colaboraciones entre agencias y funcionarios en Estados Unidos y México han afectado durante mucho tiempo a las comunidades de inmigrantes en la frontera.

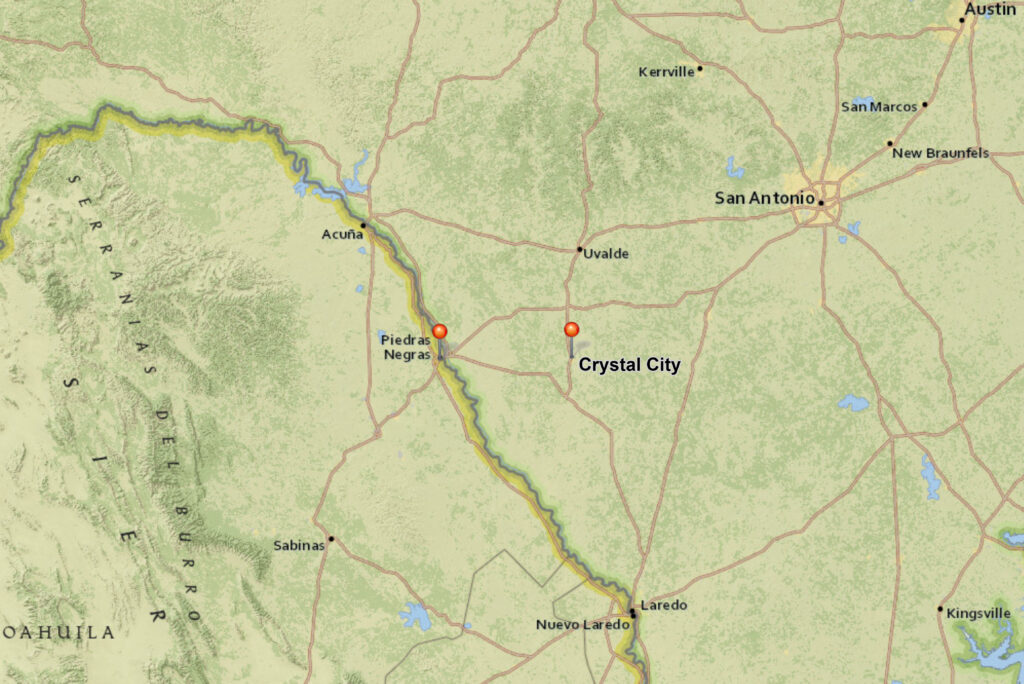

Por ejemplo, el campamento de Crystal City en Texas, cual fue inaugurado en 1942, estaba ubicado a 50 millas al este de la frontera de Eagle Pass-Piedras Negras. Este campamento se utilizó para retener a japoneses americanos, japoneses latinoamericanos y otros reclusos de ascendencia italiana y alemana. Este campamento fue operado por agentes de la Patrulla Fronteriza y del INS. Aun así, esta historia de encarcelamiento japonés no suele ser recordada dentro de las historias de criminalización y exclusión en el sur de Texas y la región fronteriza. La presencia de este campo de encarcelamiento japonés en el sur de Texas, al igual que el desplazamiento de las comunidades japonesas en el norte de México, tampoco forma parte de la memoria de las comunidades regionales. A través de ambos casos se descubren narrativas ocultas de vigilancia de las comunidades japonesas en la frontera que comenzaron décadas antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial.[5] Las historias de familias de japonesas en Estados Unidos, México y Latino América que fueron separadas también reflejan una historia más extensa de separación de familias en la frontera.

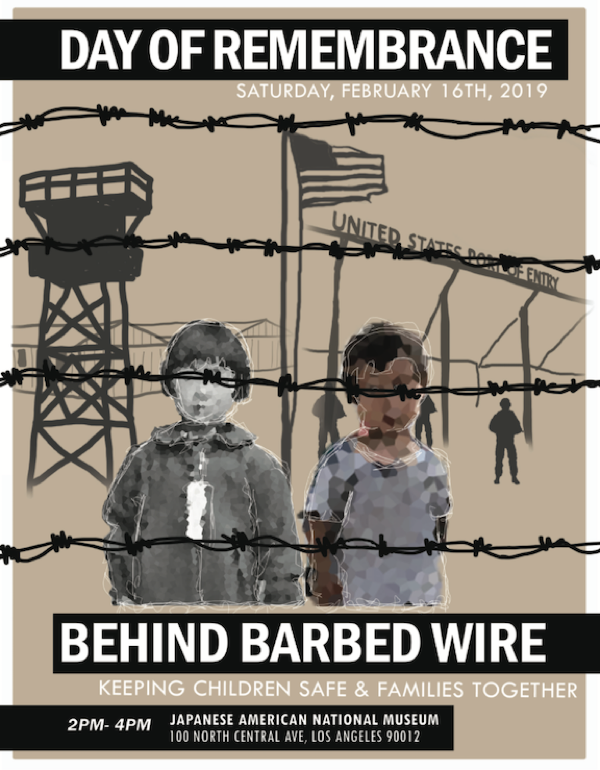

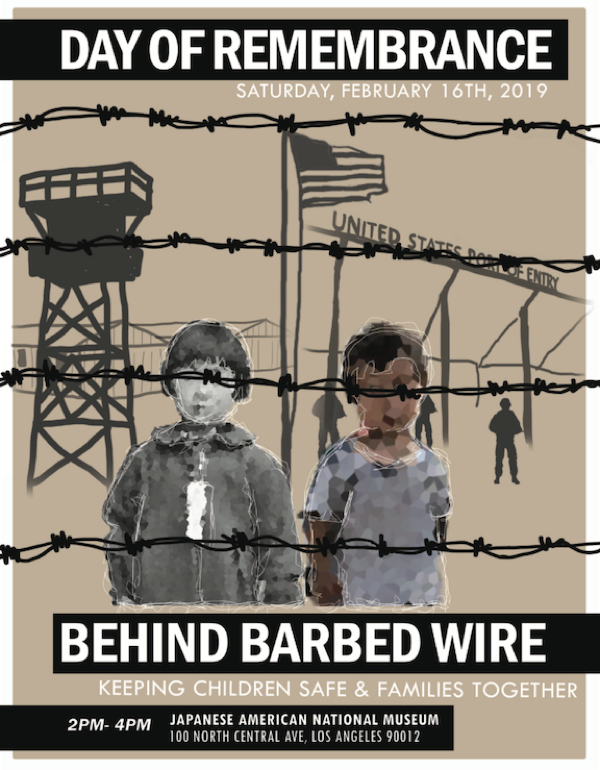

Hoy en día, artistas y organizaciones comunitarias están destacando la convergencia de formas de encarcelamiento y vigilancia policial en el pasado y el presente a través de su trabajo. Este dibujo de la artista japonesa americana Elyse Imoto ilustra las similitudes en la criminalización y violencia en las experiencias de las comunidades japonesas durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial y de los migrantes mexicanos, centroamericanos, haitianos, venezolanos y otros en la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México en los últimos años.[6] La yuxtaposición de un niño pintado en blanco y negro y el otro pintado en color marca un pasado y un presente. La niña pintada en blanco y negro parece ser una japonesa americana retenida durante el período de encarcelamiento en la década de 1940. El niño en color a la derecha parece representar a un niño mexicano o centroamericano en el presente en la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México. En el fondo se ve una torre de vigilancia, edificios que normalmente se encontraban en los campos, y un letrero que dice “Puerto de entrada de los Estados Unidos” con figuras que parecen ser agentes armados de la Patrulla Fronteriza.

La detención de migrantes ha ido en aumento desde el 2016, y del 2021 a agosto del 2022 se habían reportado 372 casos de separación de familias.[7] Los casos de separación de familias en la frontera son el resultado de políticas que condenan penalmente a los migrantes y separan a padres o adultos que intentan cruzan con niños. Uno no pensaría inmediatamente que las condiciones y el trato de los inmigrantes hoy en día en la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México estén relacionados con el trato de las comunidades japonesas y su expulsión forzada durante la guerra. Sin embargo, los encarcelados en el campamento de Crystal City y los japoneses que vivián en los estados de Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León y Tamaulipas se vieron obligados a reubicarse y dejar atrás a sus familias y comunidades. La historia del desplazamiento de japoneses durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial suele ser considerada una historia distante de la frontera entre Texas y México que no está relacionada con historias más extensas de encarcelamiento y violencia en la región. Sin embargo, las experiencias de los migrantes en el sur de Texas son parte de una normalización de violencia continua que el estado considera aceptable a través de su lenguaje y políticas para la “seguridad nacional” o contra posibles “amenazas” o “criminales.” El encarcelamiento de japoneses cerca de la frontera entre Texas y México y las actuales políticas estatales de migración y ciudadanía en la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México son parte de un proceso de exclusión que se desarrolló como resultado de la inmigración racializada y políticas del siglo XX.

En Estados Unidos, grupos como Tsuru por la Solidaridad (o Tsuru for Solidarity) están tratando de cambiar esto al compartir sus experiencias y las historias de la separación de familias durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial y así #PararDeRepetirLaHistoria (o #StopRepeatingHistory).[8] Tsuru for Solidarity es un proyecto formado por japoneses americanos y japoneses latinoamericanos que son defensores de la justicia social y sus aliados, y el grupo lidera campañas en todo Estados Unidos para educar al público sobre la historia del encarcelamiento japonés y construir solidaridades con otros grupos que son el blanco de políticas de inmigración racistas. Algunos de los participantes son miembros de familias japonesas que fueron encarceladas durante la guerra o descendientes de ex encarcelados. Ellos encabezan campañas fuera de los centros de detención de inmigrantes en todo Estados Unidos para protestar las condiciones en estos centros y en contra de políticas que permiten la separación de familias.

La historia del encarcelamiento, la expulsión forzosa y la separación de familias japonesas durante la guerra en ambos lados de la frontera entre Estados Unidos y México ilustra los legados de violencia que tienen vínculos extensos con la exclusión antiasiática de los finales del siglo XIX. El legado de estas políticas se refleja en el presente con la criminalización y el encarcelamiento de migrantes y solicitantes de asilo en la frontera. Las familias japonesas con ascendencia japonesa y activistas comunitarios en Estados Unidos y México están compartiendo sus recuerdos dentro de sus familias y comunidades, asegurándose así de que estas historias no sean olvidadas.

Lucero Estrella es candidata a doctorado en Estudios Americanos en la Universidad de Yale y actualmente es investigadora visitante en el Instituto de Estudios Históricos (IHS) de la Universidad de Texas en Austin. Su tesis doctoral es un estudio de las historias de la migración japonesa y la formación de comunidades en Texas y el noreste de México a lo largo del siglo XX. Su tesis examina cómo las comunidades mineras y agrícolas japonesas en Coahuila, Nuevo León y Texas son fundamentales para las historias de raza, migración e imperio. Utilizando historias orales con comunidades japonesas en ambos lados de la frontera y fuentes de archivos estatales y locales en México, Japón y Estados Unidos, su trabajo ilustra cómo los japoneses en México y Estados Unidos, y las fuerzas nacionales y globales que moldearon sus vidas, son importantes para las historias de México, Japón y la región fronteriza entre Estados Unidos y México.

[1] María Elena Ota Mishima, Siete migraciones japonesas en México 1890-1978 (México: El Colegio de México, 1982), 97.

[2] La vigilancia de las comunidades japonesas en el norte de México no era algo nuevo, y la vigilancia de estadounidense hacia las comunidades japonesas en México fue alimentada por las ansiedades del estado estadounidense por la expansión del imperio japonés y el miedo al “peligro amarillo” entre las décadas de 1920 y 1940. Para obtener más información, consulte los trabajos de los historiadores Eiichiro Azuma, Jerry García y Sergio Hernández Galindo: Sergio Hernández Galindo, La guerra contra los japoneses en Mexico durante la segunda guerra mundial: Kiso Tsuru y Masao Imuro, migrantes vigilados, First edition. (Mexico City: Itaca 2011); Jerry Garcia. Looking like the Enemy: Japanese Mexicans, the Mexican State, and US Hegemony, 1897-1945. (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2014); Eiichiro Azuma. “Japanese Immigrant Settler Colonialism in the U.S.-Mexican Borderlands and the U.S. Racial-Imperialist Politics of the Hemispheric “Yellow Peril”.” Pacific Historical Review 83, no. 2 (2014).

[3] Países como Perú, Panamá, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Nicaragua, El Salvador y Venezuela trabajaron con Estados Unidos para deportar y encarcelar a la fuerza a japoneses latinoamericanos en campos en Estados Unidos. Algunos japoneses que viven en México, como funcionarios de alto nivel, diplomáticos y un pequeño número de japoneses que vivían cerca de la frontera fueron encarcelados en Estados Unidos. Para obtener más información sobre el encarcelamiento de japoneses en México, consulte Selfa A. Chew, Uprooting Community: Japanese Mexicans, World War II, and the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands, (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2015).

[4] Académicos estadunidenses han debatido el uso de “internamiento” y “encarcelamiento”, entre otras palabras como “detención” y “confinamiento.” Densho, una organización japonesa americana sin fines de lucro con sede en Seattle, “alienta el uso del “encarcelamiento,” excepto en el caso específico de los japones americanos detenidos por el ejército o el Departamento de Justicia.” La historiadora Connie Chiang señala que el encarcelamiento transmite la falta de libertad que enfrentaron las personas de ascendencia japonesa y por esta razón usa “encarcelamiento” en su libro. Consulte “Terminology – Densho: Japanese American Incarceration and Japanese Internment.” Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project. https://densho.org/terminology/#incarceration; Connie Y. Chiang. Nature Behind Barbed Wire: An Environmental History of the Japanese American Incarceration. (Oxford University Press 2018).

[5] Las preocupaciones del gobierno estadunidense sobre el hecho que los inmigrantes japoneses y otros asiáticos sobrepasaran las restricciones de inmigración y cruzaran la frontera para ingresar a los Estados Unidos se extendía por toda la frontera y llegaba al norte de México y estas preocupaciones fueron alimentadas por un “peligro amarillo” transfronterizo. Estas preocupaciones no se referían sólo a la inmigración japonesa no autorizada a Estados Unidos, sino también a la formación de grandes colonias japonesas en México y a la compra de grandes concesiones por parte de los japoneses en México. Eiichiro Azuma, “Japanese Immigrant Settler Colonialism in the U.S.-Mexican Borderlands and the U.S. Racial-Imperialist Politics of the Hemispheric ‘Yellow Peril,’” PaciRc Historical Review 83, no. 2 (2014): 255–76.

[6] Este dibujo de Imoto se utilizó como cartel para el Día del Recuerdo del Museo Nacional Japonés Americano (JANM) en 2019. Se utilizó como portada de su programa, y para promocionar el evento en persona organizado en JANM en Los Ángeles.

[7] “Biden is Still Separating Migrant Kids from Their Families.” Texas Observer. November 21, 2022. https://www.texasobserver.org/the-biden-administration-is-still-separating-kids-from-their-families/.

[8] Tsuru es una grulla en japones y el símbolo del grupo es una grulla de origami. Para obtener más información sobre Tsuru for Solidarity y sus campañas y esfuerzos, consulte: https://tsuruforsolidarity.org.