From the Editors: The Not Even Past Works in Progress series highlights groundbreaking new research that is not yet published. The idea is to give our readers a first look at current projects and upcoming publications. As the first in the series, we are fortunate to feature an important new work, The Radical Spanish Empire: Petitions and the Creation of the New World, under contract with Harvard University Press.

The Radical Spanish Empire: Petitions and the Creation of the New World (Harvard University Press, forthcoming) by Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra and Adrian Masters

Our book emerged from several years of conversations as Adrian was working on his dissertation on petitioning in 16th century Spanish America. Adrian demonstrated that hundreds of thousands of royal decrees were not just top-down fiats by a distant, overbearing, authoritarian monarch but the result of bottom-up petitions by vassals. Adrian proved that royal decrees were simply verbatim copies of letters sent by vassals of many social backgrounds (including male and female elites and commoners of countless ethnic backgrounds) to the King and his Council of the Indies. This unfolding insight led us to question the “liberal” historiography’s depiction of British America as a democratic, free-thinking, and modern foil to its downtrodden, corrupt, and medieval counterpart to the South. By following the ways the Spanish monarchy’s many vassals used petitions and litigation, we began to see patterns of radical social mobility and massive bottom-up participation that most major scholarship has failed to conceptualize.

The book is a detailed analysis of how the concept of “liberal modernity” works as cluster of cognates, including among them “print culture,” “public sphere,” “Protestantism,” “Scientific Revolution,” “parliamentary democracy,” and “Enlightenment,” that render invisible other potential combinations and paths of historical transformation. Spanish America appears always as the inverted mirror image of these clusters.

The Radical Spanish Empire explores in great archival detail the intense “democratic” social mobility triggered by the conquest. The category of “absolutism” as the antithesis of liberal modernity has rendered historiographically invisible the “participatory”, bottom-up, bitterly contested creation of all legal codes and categories (local, regional, and imperial) in colonial Spanish America. It has also blinded historians to the epistemological dynamism that shaped knowledge production, particularly in the sixteenth century. The sixteenth-century Spanish Indies were characterized by intense degrees of technological and scientific innovation that transformed the global economy. This massive transformation, akin to an industrial-cum-scientific revolution in the highlands of Mexico and Peru, was not the result of new “modern” forms of sociability (the public sphere and printing press) but of traditional forms of bottom-up (even secretive and thus coded) justice paperwork and vertical communication with regional and imperial authorities, both lay and ecclesiastical.

Our conversations and investigations gradually has developed a model which explains why the Spanish American context did not become an orderly ancien régime society between 1530-1570, and why, when it finally matured from 1570 to 1600, its social order was deeply alien to Iberia and much of Europe. Namely, we pinpoint how the Spanish Americas’ gargantuan bottom-up paperwork and local archives initially frustrated indigenous elites, powerful conquistadors, and friars. Gradually, a unique trinity of New World power emerged: royal favor, local archives, and wealth. Vassals of all backgrounds who mastered these three sources of power mastered a novel ancien régime built on paper, silver, and persuasion; those who did not faded slipped into anonymity. This dramatic century was thus not only one of violence and disease, but colossal bottom-up participation in imperial rule, radical political and conceptual invention, social mobility (both upwards and downwards), and wily questioning of the most cherished indigenous and Iberian mores. This model upsets the master narratives about Spanish America’s formative century, and exposes the myths underpinning British liberal exceptionalist scholarship.

The Radical Spanish Empire focuses on an early modern empire of paper, Spanish America, that experienced radical forms of social mobilization and governance that today we associate with “modernity.” Yet these very new forms of radical modernity led paradoxically to the constitution of hierarchical ancien regimes unlike any other in Europe. Paperwork created Spanish America by first encouraging massive political participation in the business of government, collapsing through mediation and alliances European and Amerindian power elites. This same participation, however, led to the creation of top-down archives that not only slowed down the pace of change but also created a peculiarly resilient new ancien regime, neither indigenous nor European. By the late sixteenth century any individual who had royal favor, a robust personal archive, and money could secure status and generally overcome challenges about their status and ancestry. Our book seeks to explain this paradoxical trajectory of the early modern Spanish American polity, poised between radicalism (cultural, political, social and epistemological) and the immobility which we associate with societies of orders.

How to theorize the Conquest? In traditional accounts, a handful of Spaniards upended bewildered native rulers, and rapidly implemented a Catholic state modeled off of late medieval ideals, albeit with a new absolutist and authoritarian twist. Our book argues for a drastically different perspective. It begins by merging the New Conquest History, with its emphasis on indigenous politics and alliances with conquistadors, to fine-grained studies on the conquistadors’ drastic fall from power between 1530 and 1570. Quite unexpectedly, friars during this period stepped into the power vacuum caused by these twin collapses, often claiming the power to rule, judge, and even kill, only to lose power by the 1570s as well. The few historians who do acknowledge the collapse of indigenous, conquistador, and monastic power tend to explain these groups’ misfortunes as products of the Habsburg state’s absolutism, which could not tolerate powerful elites. By contrast, we argue that this triple downfall was also due to the Habsburgs’ harnessing of two great but little-explored phenomena: a deluge of bottom-up paperwork against Indies strongmen, and the universal denunciations by subjects of their feudal lords as ‘tyrants.’ For four decades, then, an ancién régime did not take hold, as ‘tyrannical’ indigenous elites, local lords (caciques), conquistador-governors, lesser conquistadors, and friars repeatedly found themselves crushed by their rivals’ petitions, litigation, and witness statements.

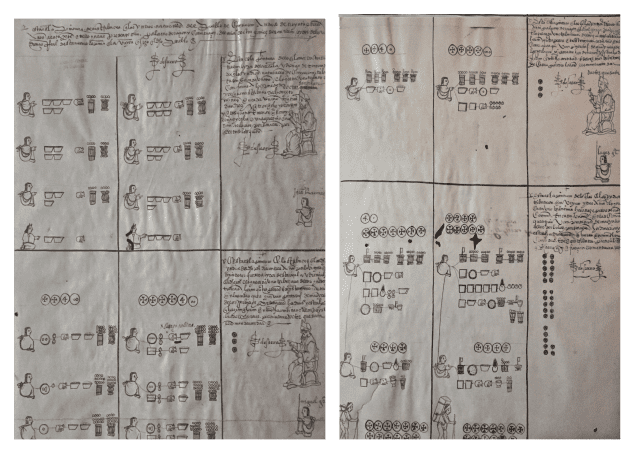

Our work calls attention to one to the most remarkable and little-known chapters of social mobilization and cross ethnic alliances through paperwork, namely, the emancipation of indigenous slaves and the rise of commoners. Drawing on a deep-seated moral and theological doubts within an Empire that assumed natives to be vassals, but that also promoted expansion by encouraging raiding, captivity, and vast internal indigenous slave markets, tens of thousands of slaves secured emancipation through petitioning via summary justice before indigenous and European judges and visitadores. Slaves often also secured some restitution and offers of resettlement. Indigenous commoners also mobilized though petitioning and paperwork, securing titles and establishing legal differences between cacique patrimonial property and community property. Commoners also wrestled political power away from old elites by either accessing political representation in indigenous municipal government or by simply separating themselves ethnically from multiethnic polities and neighborhoods and settling new lands.

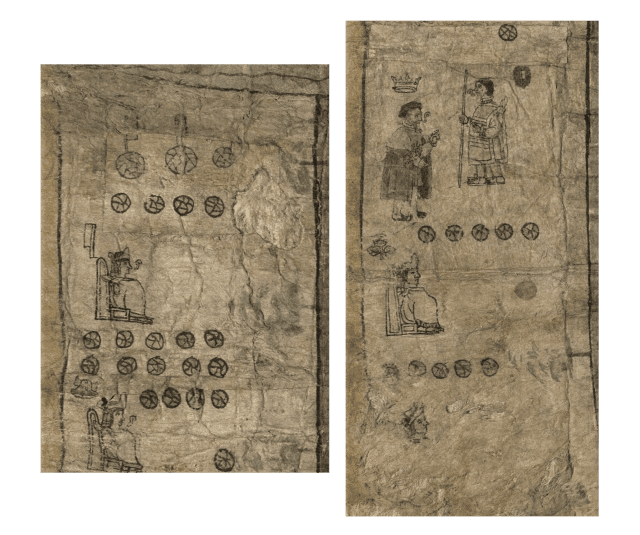

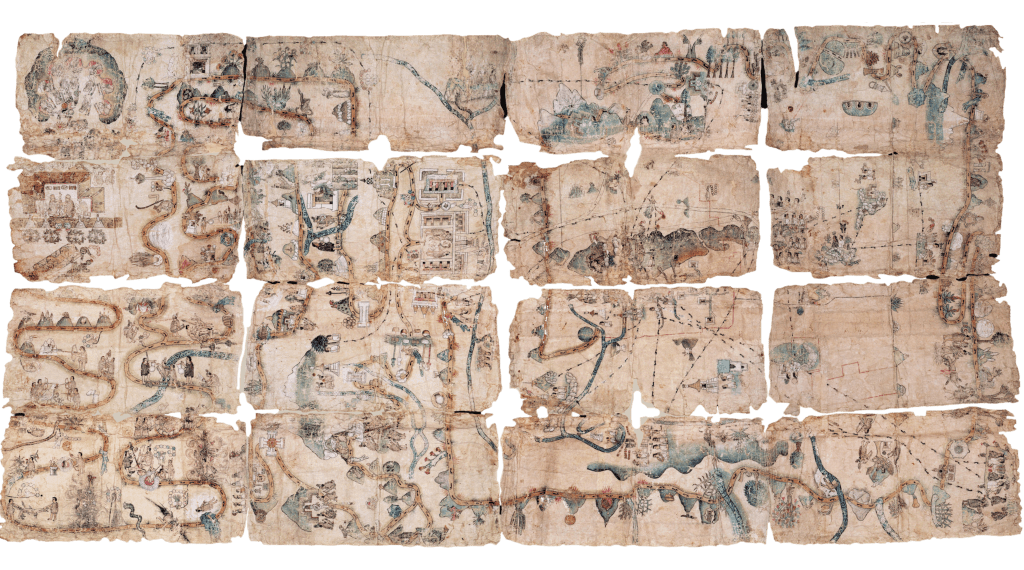

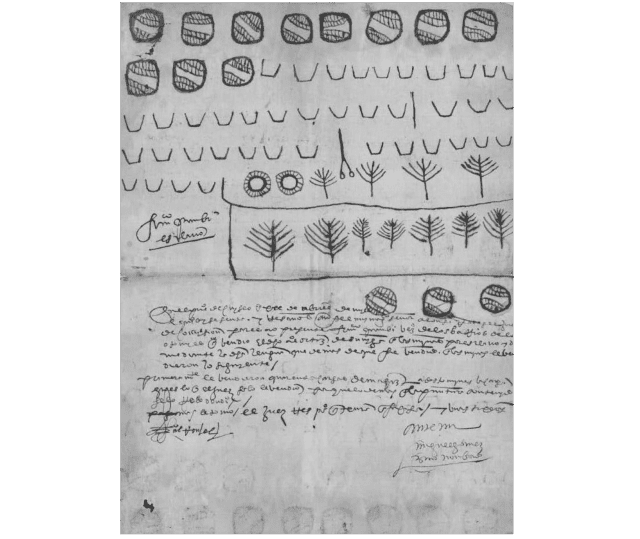

The Radical Spanish Empire seeks as well to explain how non-European knowledge and experimental science flourished through paperwork in the sixteenth century Indies. Scholars have widely regarded ‘grace’ or privilege paperwork as a conservative genre used by conquistadors to boastfully and repetitively assert their merit before the Crown. We argue this ostensibly ‘hidebound’ paperwork, considered broadly within its social context, could elicit profoundly non-traditional knowledge production – encouraging, for example, indigenous agents to produce and maintain proofs of individual, community, and regional privileges which reached back into the mists of time and used epistemological frameworks unintelligible to Spanish authorities.

Here we contest the predominant post-colonialist perspective that the Spanish conquests universally sought the downfall of indigenous epistemologies. While many scholars have correctly noted that Catholic extirpations and other forms of violence often quashed non-European ways of thinking, there are no coherent models to explain why virtually all of the New World’s surviving non-European sources arose in the 1500s. Lastly, we tie privilege-seeking and gracia petitions not only to indigenous petitions, but to knowledge-production in general – including Spanish, part-Indian, and indigenous scientific endeavors. Both these non-European and scientific epistemological frameworks which emerged in the unsettled sixteenth century all acted as auxiliaries to a single master epistemology intelligible to all: the ‘conservative’ paperwork system of gracia.

The Radical Spanish Empire argues that the Indies’ bottom-up paperwork, its distance from the royal court, its non-European epistemologies, and its feuding factions all produced a rich culture of textual skepticism. Scholars today frequently regard textual skepticism as an exclusively Northern European form of thought endemic among free-thinking liberals. Indeed, many suggest a tie between skepticism, democracy, and late modernity. We demonstrate that the furious paperwork battles of the sixteenth century Indies not only gave rise to a sustained culture of skepticism and doubt about the writing-and-word-based depiction of reality in the halls of Habsburg power, but that this skeptical culture was shared and encouraged by all Indies subjects, no matter how humble, as they sought to transform the world through paperwork.

Yet, despite all the immense social mobility and cultural and epistemological radicalism triggered by European invasion of the Americas, roughly between 1570 and 1600, a new type of ancién régime began to emerge in the Indies that was alien to the indigenous, conquistador, and monastic feudalisms which arose and collapsed in the years 1530-1570.

Scholars have identified two main reasons for this transition – the expansion of royal power in the Indies, and the replacement of feudal labor in the core regions for a complex, partly cash-based market economy. We add a third fundamental force to this model: archives. The rather innocuous boxes which all vassals’ filled with both royal privileges and money had been gradually accumulating in every household and corporation in the Indies, in the homes of the humblest Indian widow and the mightiest conquistador-governor. Major paperwork battles about wealth, jurisdiction, and social privilege hinged on these archives. The Crown, engaged in decades-long legalistic battles against its Indies rivals, began to build one of the world’s great archives by the late 1550s, ordering New World privileges, bureaucratically strangling its powerful foes, and bringing about legal standardization. Increasingly powerful royal officials – viceroys, bishops, and inquisitors – simultaneously deepened vassals needs for archives while often counteracting bureaucratization by creating their own patrimonial networks. These officials, hungry for revenue to compensate for Indian demographic collapse and expensive anti-piracy measures, allowed the commodification of status, trading money for privileges.

Money began to move entire archives, as Otomí peasants bought Moctezuma elites’ privileges, and Spaniards blackmailed rivals with Inquisition papers. Merchant families swallowed conquistador and indigenous elite branches, seeking to maximize others’ privileges to achieve greater revenues for themselves. All around, Indies textual production and society became increasingly ‘archival’ and commercial by the late 1500s. By 1600, then, vassals like the part-Tlaxcallan Diego Muñoz Camargo and others needed to master the Indies’ three cornerstones to survive and thrive: mastery of archives, royal approval, and wealth. A new ancién régime comprised of savvy vassals, rich bureaucrats, powerful officials, and merchants who consumed the privileges of anemic conquistador and indigenous lords, emerged.

The Spanish New World’s ancien régime’s rocky evolution ensured that while the Indies did not meet liberal-democratic benchmarks, it excelled in stimulating massive participation in rule, a culture of anti-tyrannical agitation, radical politics, widespread skepticism, and profound questioning of previous social orders. Many of the elements so cherished by the exceptionalist liberal British historiography were, in fact, integral to the Spanish New World. When the ancien régime finally set root in the late 1500s, its more ossified structures now presented vassals with a challenging but sometimes attainable pathway to elite status: not through blue blood or money alone, but through deft exploitation of paperwork. This society was neither purely feudal and violent, nor fundamentally capitalistic. It was underpinned as well by an unlikely third force: millions of inert and innocuous pieces of paper.

Dr. Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra is the Alice Drysdale Sheffield Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Adrian Masters completed his Ph.D. at UT in 2018 and is currently a post-doctoral fellow at Eberhard Karls Universität in Tübingen.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.