By Randolph Lewis, Editor TEAO and Associate Professor, American Studies, UT-Austin

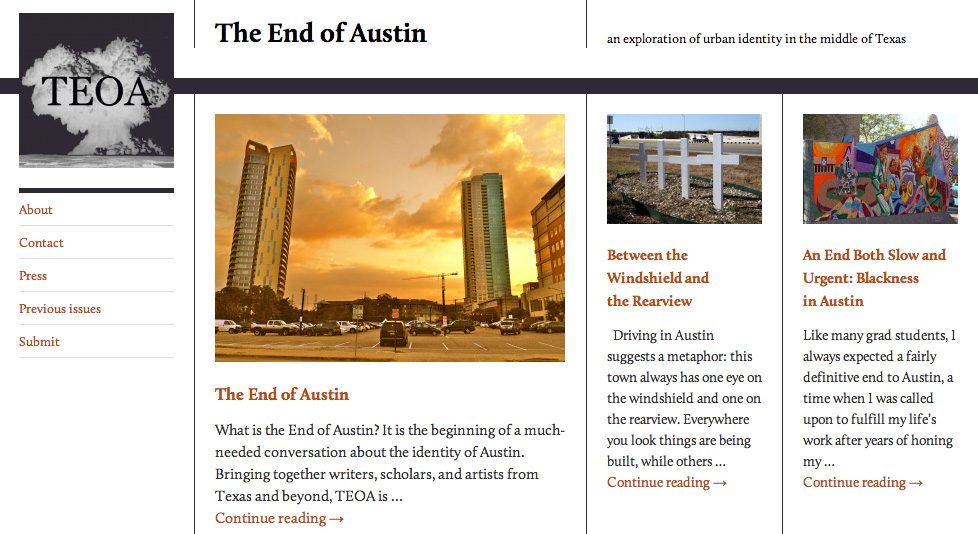

A city of perpetual nostalgia, Austin is a vivid place where rapid change pulls against profound attachments to the way things are (or how they are imagined to be). Perhaps this dynamic is what gives such poignancy to the idea of endings in Austin. Austinites are always afraid of losing what we love about the city: the vibe of a particular neighborhood, the murmur of the so-called creative class, the beauty and health of Barton Springs. The end of Austin, or at least some beloved facet of it, always seems around the corner, haunting our sense of place. Austin will probably never end in a literal sense, but our project is dedicated to marking and mourning the small endings that are happening on its streets each day. Certainly, there are those who believe that Austin is already dying, as my animation of actual Austin laments might suggest.

What is The End of Austin? It is the beginning of a much-needed conversation about the identity of Austin. Bringing together writers, scholars, and artists from Texas and beyond, TEOA is a place to wrestle with the hype and hope of living in what is now “the fastest-growing city in the US.” How do we preserve what we love about this place as it moves toward a projected population of 3.5 million in 2040? What have we lost already? Is urban nostalgia a productive fantasy that bonds us to a particular vision of place or a dead-end lament for the way we never were? Those are the essential questions for TEOA, a new online publication that will appear twice a year with a robust mix of art, music, scholarship, creative writing, photography, and video about Austin’s shifting identity.

Why try to create this sort of collaborative work on the boundary between art, journalism, and scholarship? The answer reflects our roots in the American Studies Department at UT-Austin. For us, American Studies is a constant invitation to try new things, and perhaps the best place to experiment is in our own backyard. We hope to make American Studies into something ever more evocative, powerful, and relevant to people inside and outside of the academy. Traditional forms of academic output are important, but we have other contributions to make, other voices in which to address a multitude of publics, including right here in Austin.

I think Austin is particularly ripe for this sort of endeavor because the city defines itself so passionately in terms of its recent past. In many ways, Austin came of age in the 1970s and 1980s, in the sleepier decades of “cosmic cowboys,” Stevie Ray Vaughn, and Slacker. For the first time, a Texas city seemed cool in a way that impressed bi-coastal style mavens. What had been a laidback small city with a large university and the vast machinery of state politics suddenly became the epicenter of “third coast” style. By the late 1990s, Austin was a national brand that meant music festivals, serious cycling, high tech industry, and a gentle spirit of lone star weirdness. Yet something seemed to complicate this sunny (and some would say inflated) self-regard almost as soon as it emerged. Rapid population growth and sometimes ill-considered development led to a new Austin reality: endless sprawl, epic traffic jams, unaffordable real estate, and gentrification that pushed out communities of color in favor of noise-hating neo-yuppies and yarn-bombing, beard-sporting, artisan beer sipping hipsters.

Indeed, Austin has struggled mightily with its own success in the past decade. Locals began to complain that their beloved city was turning into just another sunbelt metroplex—or even worse, Dallas. Not being Dallas remains a point of pride for many Austinites, who define themselves in funky opposition to the rest of Texas in general and the big D in particular (sorry Dallasites: I’m describing here, not endorsing). Our detractors might see our obsession with “keep Austin weird” as pretentious and hollow, but it reflects a genuine anxiety about the shape of things to come. Would glitz and growth push aside the quiet charms that once made Austin so attractive (I’m thinking back to when my parents met here in 1961, or when my wife and I met in 1985)? Would Austin lose its soul?

The results so far have been mixed. It’s always tough slowing “progress” in the name of history, aesthetics, community, or even social justice, but old school Austinites have staved off the “end of Austin” with occasional success. The continued health of the Treaty Oak, Cactus Café, Barton Springs, and Broken Spoke suggest that it is possible to preserve the old places, even if it means literally surrounding an old honkytonk joint with a towering maze of new condos, as is happening to the Spoke right now. Such victories, partial as they may be, have required an appeal to our shared history. After all, an awareness of what happened here, an appreciation of how things evolved, even a bit of melancholy over what has disappeared—this is what anchors us emotionally to a place and makes a city into a home. I wouldn’t choose to live in Austin if it became interchangeable with Phoenix, Atlanta, or Houston, simply because I am invested in our unique “texture of place,” as my colleague Steve Hoelscher calls it. And that texture, I suspect, cannot thrive without a shared awareness of the interplay of past and place. If we do not collectively mark, mourn, and respect our urban history, we risk spending our lives in a sterile built environment that provides material comfort, but none of the spiritual, communal, and intellectual pleasures that a great city can offer. We will find ourselves in the proverbial “geography of nowhere,” and that is a dull and dusty place indeed.

Rather than the dreary exhortation to “keep Austin weird,” I would rather “Make Austin Great.” I am devoid of boosterism when I say this. Despite all of the hype, we are not a great city: we remain too segregated by class and race; too marred by failing infrastructure; too uncertain of how to manage our rapid growth. But with the right conversation between scholars, community members, artists, and activists, I am hopeful about what Austin might become.

This is the rationale behind TEAO. With American Studies grad students Carrie Andersen, Sean Cashbaugh, Greg Seaver, and Emily Roehl, I’ve formed an editorial board to assemble new issues of TEAO that explore Austin’s changing identity. With an eye toward our next issue in Summer 2013, we are looking for original voices from across the US with something to say about Austin’s changing identity. We hope you’ll join the conversation.

You may also enjoy:

Bruce Hunt, City Lights: Austin’s Historic Moonlight Towers

Madeline Hsu, Family Outing in Austin, Texas

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

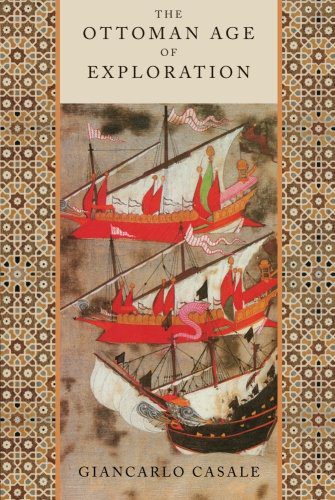

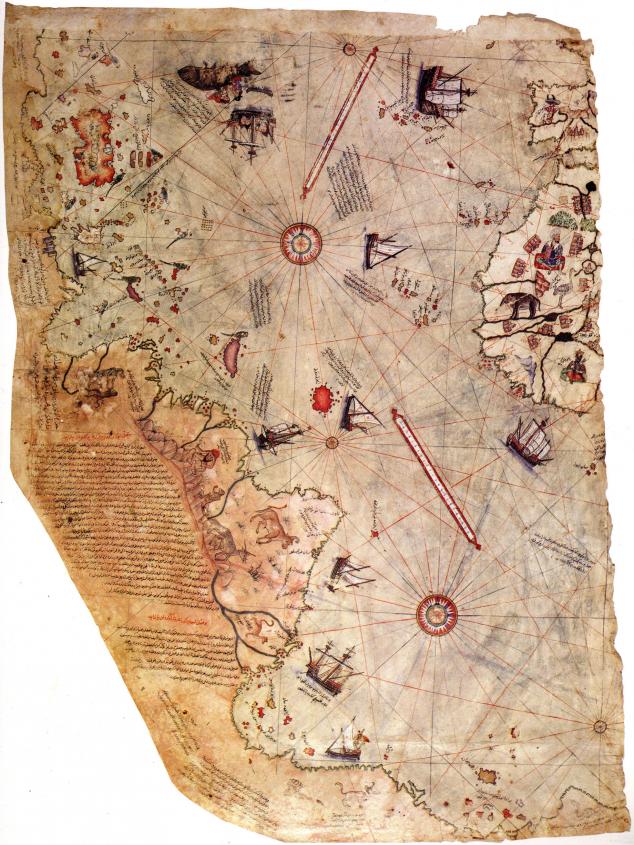

In The Ottoman Age of Exploration, Giancarlo Casale contests the prevailing narrative that characterizes the Ottoman Empire as a passive bystander in the sixteenth-century struggle for dominance of global trade. Using documents from archives in Istanbul and Portugal, Casale shifts our attention east and demonstrates that the Ottomans were actively engaged as rivals to the Portuguese for control of the lucrative spice trade and sea lanes of the Indian Ocean.

In The Ottoman Age of Exploration, Giancarlo Casale contests the prevailing narrative that characterizes the Ottoman Empire as a passive bystander in the sixteenth-century struggle for dominance of global trade. Using documents from archives in Istanbul and Portugal, Casale shifts our attention east and demonstrates that the Ottomans were actively engaged as rivals to the Portuguese for control of the lucrative spice trade and sea lanes of the Indian Ocean.

minority women’s experiences. Scholars like Ruthe Winegarten have published books about tejanas and black Texas women. In this area, however, there is still room for improvement. Cynthia Orozco, a professor of History at Eastern New Mexico University, underscored the persistent scarcity of Latina and other minority historians. She was emphatic in her challenge to current historians to support Latina/o students who show a potential for historical research and writing. Her own academic trajectory is replete with examples of the immense challenges that women of color face along the path toward becoming academic historians. She received her B.A. from The University of Texas at Austin in 1980, but was advised to accept an offer of graduate admission at UCLA because it was one of the few institutions where she would have enough support to become a historian of Chicana/o history.

minority women’s experiences. Scholars like Ruthe Winegarten have published books about tejanas and black Texas women. In this area, however, there is still room for improvement. Cynthia Orozco, a professor of History at Eastern New Mexico University, underscored the persistent scarcity of Latina and other minority historians. She was emphatic in her challenge to current historians to support Latina/o students who show a potential for historical research and writing. Her own academic trajectory is replete with examples of the immense challenges that women of color face along the path toward becoming academic historians. She received her B.A. from The University of Texas at Austin in 1980, but was advised to accept an offer of graduate admission at UCLA because it was one of the few institutions where she would have enough support to become a historian of Chicana/o history.

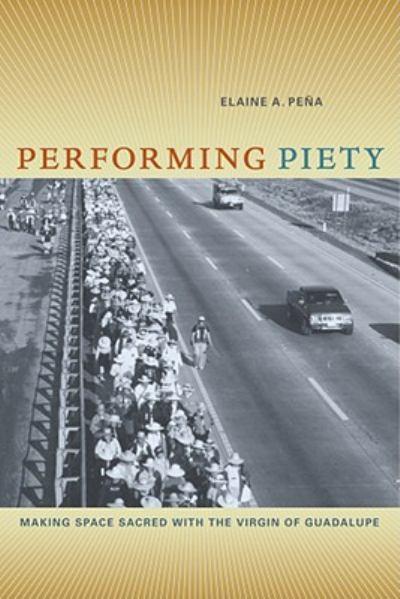

Once they arrive at the Basilica at Tepeyac, the women attend an early-morning mass then take a ride on a conveyor belt that will transport them to the sixteenth-century image of the Virgin. Peña describes the moment of passing in front of Juan Diego’s tilma as a profound one for which words do not suffice. Peña joined two of these groups on their ritual of devotion to la Virgen. Her active participation, which Peña calls “co-performative witnessing,” helped her realize that while the Virgin of Guadalupe brought people together to a specific location, it was their embodied practices—prayer, song, dance, shrine maintenance—that imbued these sites with holiness.

Once they arrive at the Basilica at Tepeyac, the women attend an early-morning mass then take a ride on a conveyor belt that will transport them to the sixteenth-century image of the Virgin. Peña describes the moment of passing in front of Juan Diego’s tilma as a profound one for which words do not suffice. Peña joined two of these groups on their ritual of devotion to la Virgen. Her active participation, which Peña calls “co-performative witnessing,” helped her realize that while the Virgin of Guadalupe brought people together to a specific location, it was their embodied practices—prayer, song, dance, shrine maintenance—that imbued these sites with holiness. a novel, especially such a well-known and prodigious novel like Victor Hugo’s 1862 Les Misérables, is even riskier. But after the opening weekend alone, the new Les Misérables is already considered a commercial success with an estimated $18.2 million in box office receipts and many favorable reviews. Overall, Les Misérables is an intense, moving, and beautiful film that will undoubtedly receive numerous award nominations in the next few months and I highly suggest that you add it to your holiday season watch list. But while the 2012 Les Misérables is a moving and entertaining film musical, it lacks historical context and may leave viewers scratching their heads about basic plot elements.

a novel, especially such a well-known and prodigious novel like Victor Hugo’s 1862 Les Misérables, is even riskier. But after the opening weekend alone, the new Les Misérables is already considered a commercial success with an estimated $18.2 million in box office receipts and many favorable reviews. Overall, Les Misérables is an intense, moving, and beautiful film that will undoubtedly receive numerous award nominations in the next few months and I highly suggest that you add it to your holiday season watch list. But while the 2012 Les Misérables is a moving and entertaining film musical, it lacks historical context and may leave viewers scratching their heads about basic plot elements.

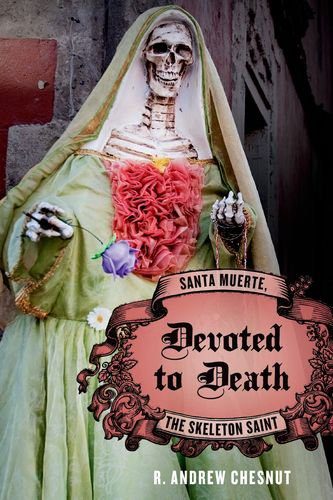

tobacco lying as an offering at her feet. Votive candles of various colors surrounded the statuette, as well as regularly replenished glasses filled with water and Mexican tequila. The officers had found Santa Muerte.

tobacco lying as an offering at her feet. Votive candles of various colors surrounded the statuette, as well as regularly replenished glasses filled with water and Mexican tequila. The officers had found Santa Muerte.