My thesis focused on tracing and analyzing the complicated political conversations within the women’s division of the Mexican Catholic Action, specifically regarding women’s suffrage from the late 1930s to the early 1950s. My work revealed a layered set of beliefs that defy these women’s simple classification into feminist or antifeminist categories. Their complex reconciliation of conservative views with more progressive ones is a trend that has also been found in the historiography of international Christian women’s organizations through various time periods.[1] In a relatively recent article, Mexican historian Pedro Espinoza Meléndez also identifies seemingly opposing currents of thought present in ACM women’s publications.[2] In this way, my research builds on new scholarship to suggest the need for frameworks that avoid the feminist/antifeminist binary we may be inclined to apply. We should especially be careful if Western interpretations of these terms are being used to explain phenomena in non-Western regions.

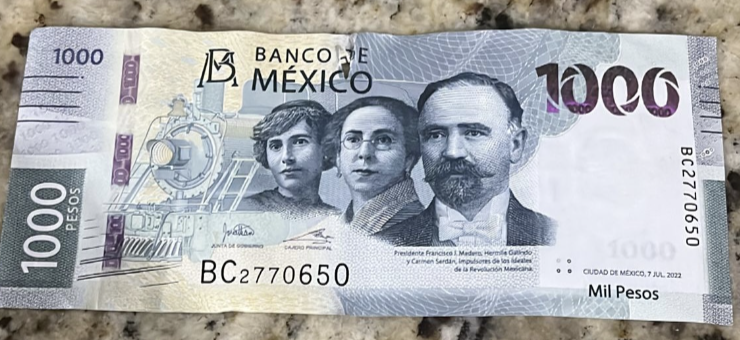

Mexican women did not obtain the right to vote in federal elections until 1953, although there were important antecedents to this final victory dating back at least to the Revolution. One of the reasons for this was the fear that they would infuse national politics with more conservative ideas. Some primary sources provide evidence not necessarily for the validity of these fears, but definitely for their existence and influence in the 1930s. For example, in a speech given at the first National Women’s Congress in 1936, activist Esther Chapa said that many believed “woman is influenced by the most conservative and reactionary currents, and can therefore tip the general politics of the country to the right.”[3]

It is significant also that Chapa declared this fear, rather than other, more overtly misogynistic ideas (which she also discussed) to be the excuse “that is most energetically used by certain enemies of women’s votes.”[4] Of course, she vehemently denies that these concerns should be taken seriously. Based on other sources, historians have also generally agreed that the precarious political establishment at the time feared that women’s participation would derail them from a progressive political path.[5] For example, one of the first historians of women’s fight for suffrage in Mexico, Ward M. Morton from the University of Florida, cited the enfranchisement of Spanish women in 1933—which resulted on a rightward swing in Spanish politics—as one of the key causes for hesitation on the part of left-leaning or centrist Mexican officials in the 1930s.[6]

There is value in this explanation, but the extent to which these fears were founded is difficult to assert. What is clear, however, is that these ideas were significant at the time, and have permeated into the historiography. In my opinion, one way of getting closer to a nuanced view of the issue is to refrain from treating women as a monolithic group in Mexican society, especially in such a crucial moment of development for the nation’s democracy and larger political apparatus. Because the women of the Mexican Catholic Action promoted ideas from both the right and the left, the study of their beliefs is particularly useful in this endeavor.

When looking at Catholic women’s opinions on the vote, it is crucial to define the elements that made the struggle singularly complex in Mexico. First, due to the wording of the Mexican Constitution, women’s political rights always included two related, but distinct goals—the right to vote and the right to get elected. Inextricably connected, these were fought for and obtained simultaneously in Mexico, unlike in many other countries. This may appear to be a trivial difference. Its significance becomes clear, however, when remembering the previously-explained fear of a women-led hit to progressive political parties and policies. With both ballot boxes and federal offices opening up to women, these fears would have reasonably been amplified.

I should also note that due to their reputed conservatism, it was traditional, Catholic women—such as those in the Mexican Catholic Action—who were the most blamed for the potential setbacks that would come from women’s enfranchisement. As I will demonstrate, while they did hold some conservative ideas, these were paired with more left-leaning attitudes, eventually including unequivocal support for suffrage. The study of their point of view is therefore especially interesting and significant. Gendered conceptions of citizenship responsibilities further compounded the challenges women faced in the fight for political rights.[7]

At least three additional contextual factors must be explained prior to any exploration of Catholic women’s political views from the 1930s to the 1950s. The first is the emergence and promotion of Catholic social doctrine in Rome starting in the late 1800s. Generally speaking, Catholic social doctrine was the church’s ideological response to significant events such as industrialization, the rise of communism, and large-scale warfare, conceived largely to maintain relevance in the face of these and other global trends. Some of its principles included the right to own private property, a condemnation of communism as well as unfettered capitalism (a debate that would become especially relevant post-WWII), and the basic dignity of human beings. As will be detailed later, Mexican women actively interpreted Catholic social doctrine, using it as basis for their political goals, including obtaining the right to vote.

The second important background event is the Mexican Revolution. On the one hand, revolutionary characters and ideals—including the expansion of democracy—proved to be of extreme value for many post-Revolution political factions. Indeed, the party that would command the executive branch of government from 1929 to the year 2000, was the National Revolutionary Party (later named the Institutional Revolutionary Party). By the late 1940s, Catholic women would adduce revolutionary principles to explain why granting them political rights was in line with the perceived promises of the revolution.

Third, we must understand the nature of church-state relations in Mexico. The Cristero War (1926-1929) brought the tensions between the church and the post-Revolutionary Mexican state to the battlefield. As the war ended, various Catholic lay organizations that had previously engaged with national politics merged to form The Mexican Catholic Action (ACM) in 1929, during the papacy of Pius XI. Although most members of the ACM were from the middle and upper classes, they also had growing peasants’ divisions and chapters across the country. Some historians have argued that the incorporation of many Catholic lay organizations translated into a general decrease in their political involvement, as Catholic Action groups worldwide were directly under clerical authority.[8] Other historians, such as Kristina Boylan, have found that female members—who were the majority—actually retained and fostered the political streak of earlier Catholic lay groups in Mexico.[9]

Catholic social doctrine, especially papal encyclicals associated with its theory, was widely discussed and promoted in ACM circles. Pope Leo XIII’s famous Rerum Novarum encyclical in 1891 is widely regarded as one of the founding documents of Catholic social doctrine.[10] In it, the church proposed it as a way to inter-class harmony, emphasizing Christian charity.[11] In the ACM, this particular encyclical and a few others were especially celebrated. For example, in a report from the co-secretary of the ACM’s central committee from June 25th, 1939, one of the forms outlined discussed plans for the formation of study circles for social education, in preparation for the 50th anniversary of the Rerum Novarum.[12] Later, Popes Pius XI and Pius XII cited and expanded its philosophy. Aside from his additions to Catholic social doctrine, Pope Pius XI actively encouraged the foundation of Catholic Action groups around the world.

Building on Boylan’s research on ACM women’s activism, I proposed that although the women of the Mexican Catholic Action enthusiastically followed the pope and were heavily influenced by Catholic social doctrine, they also actively interpreted, modified, and spread messages from Rome according to their interests. For example, while Rerum Novarum suggested that a woman was “by nature fitted for home-work” in order to raise children, the ACM adopted a wider interpretation of this role.[13] A 1938 article titled “Prepare Yourself for our Assembly,” meant to be read prior to that year’s national assembly of the young woman’s division, argued that all women have social duties, “whether it falls upon them to become mothers or…whether their maternity is purely spiritual.”[14]

By this perception, women should act as mothers towards their own children, but also to anyone who needs a mother, and towards the Mexican nation. Introducing a spiritual maternity into the lexicon reflects how these women managed to marry conservative political views, such as their opposition to divorce and critiques of certain media, with more liberal ones, like their support for suffrage and women’s ability to take up professional roles. The adoption of these seemingly adversary attitudes demonstrates that rather than passively obeying papal precepts, Catholic women actively shaped their meaning. Eventually, and especially as church-state relations became less combative, ideas such as these would become part of the basis for their support of suffrage.

The Mexican Revolution and the fervent patriotism that followed it also underpinned the ACM’s gradual embrace of enfranchisement. In 1947, women in Mexico finally received voting rights, albeit limited to local elections. That same year, the ACM disseminated a bulletin titled My Vote as a Mexican Catholic Woman. It was written by Emma Galán, who had served as president of the ACM’s young women’s division and had thus been part of the ACM’s Central Committee. In the publication, Galán devoted a whole section to “the aggrandizement of Mexico” and declared that voting was “a moral duty in the face of love for the Motherland.”[15] Invoking the Mexican Revolution, the document also reveals that women viewed enfranchisement as the achievement of its goals, supporting the expansion of suffrage to include voting in federal elections as well. To Galán, it was anti-revolutionary and anti-patriotic to abstain from voting or to oppose suffrage.

Galán also offers that not voting was also anti-Catholic. The ACM first adopted this position around 1939, though initially, they didn’t explicitly include women.[16] Eventually, though, political circumstances led to women’s incorporation. The ACM was vocally against the secularization of schools, for example, and since education issues were traditionally viewed as part of women’s realm, they became assets in this political fight. Bringing women into the fold through the vote would, therefore, advance their political goals, goals that would at the same time bring about a Mexico that was in line with Catholic social doctrine. Beyond secularization in schools and other such concerns, there was a persistent belief that unfettered capitalism, and most especially communism, were preventing the ACM’s idealized, Catholic Mexico—one that reflected Catholic social doctrine as they saw it—from flourishing. In this way, giving pious women the right to vote was not against Catholic social doctrine, but a benefit to its spread.

Overall, I hope my investigation of Catholic women’s discourse surrounding suffrage contributes to the perspective that different groups of women throughout history have defined their role and purpose differently, drawing from multiple theories and doctrines. It is hard, therefore, to apply or even find a general rule that defines all women in a given time period. Instead of attempting to do so, I have carefully analyzed the views of a limited sample—those of the women in the Mexican Catholic Action, who themselves embody a complex intermingling of ideas. These women incorporated both national and international considerations—such as papal precepts, and the revolution’s legacy—into their political consciousness, and in doing so they were denoting the meaning of femininity. Their support for suffrage and women’s work outside the domestic sphere was accompanied by some conservative ideals, especially when it came to divorce, sexuality, and general impropriety, as Espinoza Meléndez found.[17]

They viewed the vote as an essential tool to bring about a very specific version of Mexico, one in which neither unfettered capitalism nor communism took root, as generally validated by Catholic social doctrine. In the context of the Cold War and the unstable post-revolutionary political landscape, these views had important implications. Needless to say, ACM activists’ vision of Mexico was different than that imagined by other political groups. By recognizing these complexities, we can begin to understand and humanize historical subjects more fully. Considering a diversity of historical opinions, especially those expressed by women, can get us closer to answering questions that historians have asked for decades. I also suggest that the study and characterization of their brand of patriotism, as well as their views of modernity should continue to be researched.

Daniela Roscero Cervantes graduated from the University of Texas at Austin in 2023, receiving degrees in history and journalism. This article is based on her history thesis, Conservative “feminists”: Women’s Citizenship, Suffrage and Political Representation I Mexican Catholic Discourse, 1940-1953. She is currently enrolled at the University of Chicago to complete a master’s in social sciences with a concentration in history. Her research interests focus on modern Mexico, as well as the history of the borderlands, Mexican-Americans, and U.S.-Mexico relations.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Benson Latin American Library Rare Books collection, The University of Texas, Austin, Texas.

Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum, accessed December 7, 2023, Vatican.va.

Mexican Bulletins Collection. UNAM, Mexico City, Mexico.

Mexican Catholic Action Collection. Iberoamerican University, Mexico City, Mexico. Mexican Bulletins Collection. UNAM, Mexico City, Mexico.

Secondary Sources

Bard, Christine. “L’apotre Sociale et L’ange du Foyer: les Femmes et la C. F. T. C. a Travers Le Nord Social (1920-1936).” Le Mouvement Social no. 165, (1993): 23-41

Barry, Carolina and Enriqueta Tuñón Pablos. “Capítulo 9: Las Sufragistas Mexicanas y su Lucha por el Voto,” In Sufragio Femenino: Prácticas y Debates Políticos, Religiosos y Culturales En Argentina y América edited by Carolina Barry, 250-278. Buenos Aires: Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, 2011.

Blasco Herranz, Inmaculada. “Citizenship and Female Catholic Militancy in 1920s Spain.” Gender & History 19, no. 3 (2007): 441-466.

Boylan, Kristina A. “Gendering the Faith and Altering the Nation: Mexican Catholic Women’s Activism 1917-1940.” In Sex in Revolution: Gender, Politics, and Power in Modern Mexico, edited by Jocelyn Olcott, Mary Kay Vaughan, Gabriela Cano, 199-222. North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2007.

Boyle, Joseph. “Rerum Novarum.” In Catholic Social Teaching: A Volume of Scholarly Essays, edited by Gerard V. Bradley and E. Christian Brugger, 69–89. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Cano, Gabriela. “Mexico: The Long Road to Women’s Suffrage.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Women’s Political Rights, edited by Susan Franceschet, Mona Lena Krook, Netina Tan, 115-127. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Ceballos Ramírez, Manuel. “Historia De Rerum Novarum en Mexico (1891).” In El Catolicismo Social: un tercero en discordia, Rerum Novarum, la “cuestión social” y la movilización de los católicos mexicanos (1891-1911). Mexico City: El Colegio de México, 1987.

Dau Novelli, Cecilia. Società, chiesa e associazionismo femminile: l’Unione fra le donne cattoliche d’Italia (1902-1919). Rome: AVE, 1988.

Espinoza Meléndez, Pedro. “Antifeminismo y feminismo católico en México: La Unión Femenina Católica Mexicana y la revista Acción Femenina, 1933-1958.” Revista Interdisciplinaria de Estudios de Género de El Colegio de México 6, no. 6 (2020). http:// dx.doi.org/10.24201/eg.v6i0.381.

Morton, Ward M. Woman Suffrage in Mexico. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1962.

[1] Christine Bard, “L’apotre Sociale et L’ange du Foyer: les Femmes et la C. F. T. C. a Travers Le Nord Social (1920-1936),” Le Mouvement Social 165 (1993): 23-41.

Cecilia Dau Novelli, Società, chiesa e associazionismo femminile: l’Unione fra le donne cattoliche d’Italia (1902-1919) (AVE: 1988).

Inmaculada Blasco Herranz, “Citizenship and Female Catholic Militancy in 1920s Spain,” Gender & History Vol. 19, No. 3 (2007): 441-466.

[2] Pedro Espinoza Meléndez, “Antifeminismo y feminismo católico en México. La Unión Femenina Católica Mexicana y la revista Acción Femenina, 1933 – 1958.” Revista Interdisciplinaria de Estudios de Género de El Colegio de México 6, no. 6 (2020) http://dx.doi.org/10.24201/eg.v6i0.381.

[3] Esther Chapa, The right to vote for women, 1936, p.9, Benson Latin American Library Rare Books collection, The University of Texas, Austin, Texas.

[4] Esther Chapa, The right to vote for women, 1936, p.9, Benson Latin American Library Rare Books collection, The University of Texas, Austin, Texas.

[5] Carolina Barry and Enriqueta Tuñón Pablos, “Chapter 9: Mexican Suffragists and Their Fight to Obtain the Vote,” in Sufragio Femenino: Prácticas y Debates Políticos, Religiosos y Culturales En Argentina y América (Caseros, Argentina, Buenos Aires: Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, 2011), p. 261-265.

[6] Ward M. Morton, Woman Suffrage in Mexico (Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1962), p. 21-25.

[7] Gabriela Cano, “Mexico: The Long Road to Women’s Suffrage,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Women’s Political Rights(London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), p. 119.

[8] Manuel Ceballos Ramírez, “The Rerum Novarum Encyclical in Mexico (1891)” in El Catolicismo Social: un tercero en discordia, Rerum Novarum, la “cuestión social” y la movilización de los católicos mexicanos (1891-1911) (Mexico City: El Colegio de México, 1987), 51-67.

[9] Kristina A. Boylan, “Gendering the Faith and Altering the Nation: Mexican Catholic Women’s Activism 1917-1940,” in Sex in Revolution: Gender, Politics, and Power in Modern Mexico, ed. Jocelyn Olcott, Mary Kay Vaughan, Gabriela Cano (North Carolina: Duke University press, 2007), 210-234.

[10] Joseph Boyle, “Rerum Novarum,” in Catholic Social Teaching: A Volume of Scholarly Essay, ed. Gerard V. Bradley and E. Christian Brigger, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 68-89.

[11] Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum, 22, 24, 30, 61, 63.

[12] Report of the co-secretary for June 25th 1939 Central Committee Meeting, 22 May 1939, 2.2.1.1 Sessions of the Central Committee 1930-1978 box 1, folder 2 1934-1939, Archivo ACM, Iberoamerican University, Mexico City, Mexico.

[13] Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum, 42.

[14] Anonymous, “Prepare Yourself for Our Assembly,” Juventud, September 1938, 16, Section 6-Publications, box 7, bound book starting 1938, Mexican Catholic Action Collection, Iberoamerican University Historical Archives, Iberoamerican University, Mexico City, Mexico.

[15] E. Emma Galán G., bulletin titled “My Vote as a Mexican Catholic Woman,” 13, 35 Mexican Bulletins Collection, National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), Mexico City, Mexico.

[16] Notice number twenty-three from the Central Committee, ca. May 1939, 2.2.1.1 Sessions of the Central Committee 1930-1978 box 1, folder 2 1934-1939, Archivo ACM, Iberoamerican University, Mexico City, Mexico.

[17] Pedro Espinoza Meléndez, “Antifeminismo y feminismo católico en México. La Unión Femenina Católica Mexicana y la revista Acción Femenina, 1933 – 1958.” Revista Interdisciplinaria de Estudios de Género de El Colegio de México 6, no. 6 (2020) http://dx.doi.org/10.24201/eg.v6i0.381.

Banner image via Pexels – Photo by Luis Ariza: https://www.pexels.com/photo/mexican-flag-on-flagpole-13808918/

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.