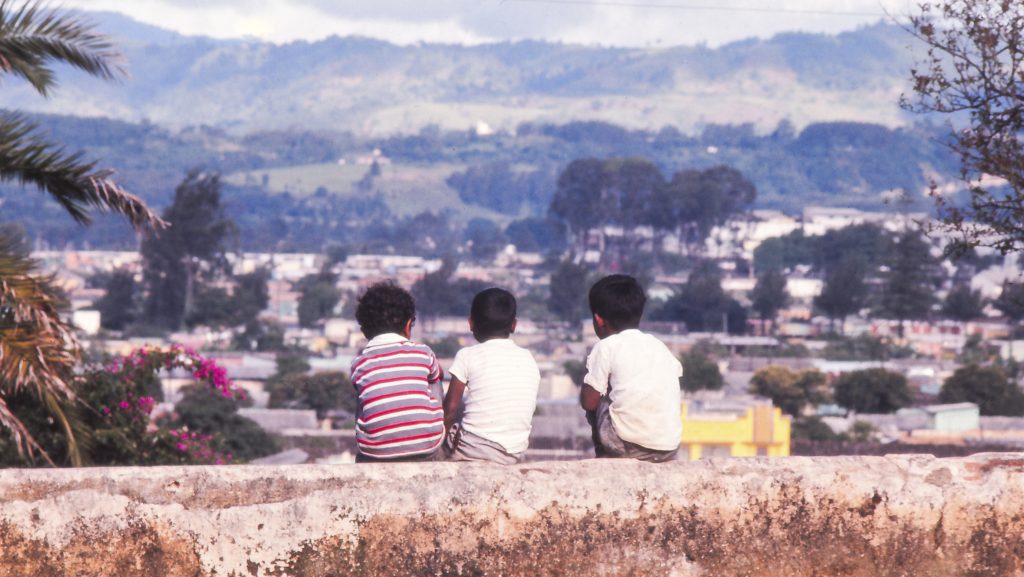

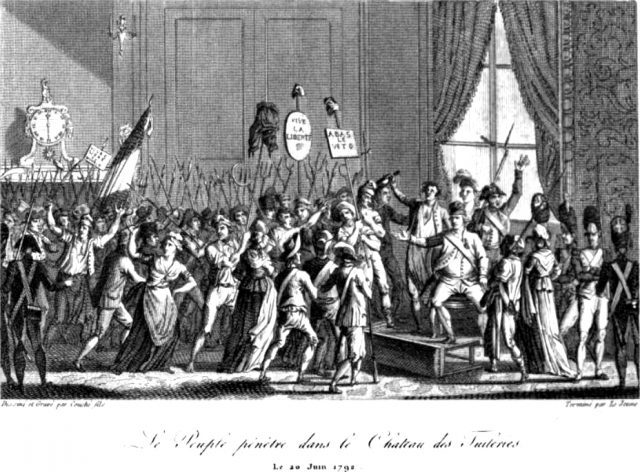

Two young Guatemalan soldiers abruptly pose for the camera. They rush to stand upright with rifles at their sides. On a dirt road overlooking an ominous Guatemala City, they stand on guard duty. This snapshot formed the title page of an exhibit at the University of Texas at Austin’s Benson Latin American Collection in 2018. A collection of these and other documents by Rupert Chambers will become part of a permanent archive at the library. The photographs depict the year 1966, a time of martial law and increasing state repression of leftist movements and supporters of reform. A storm was brewing in Guatemala.

Historians can situate this collection of photographs in the context of Guatemala’s civil war. The Guatemalan military was mobilizing to eliminate leftist guerrilla armies, which had recently arrived on the scene. Leaders of these rebel armies framed their struggle in the hope of democratic reform. The Guatemalan state would not budge. The state military agenda rested on two pillars: fierce Cold War anti-communism and protection of the Guatemalan oligarchs’ monopoly on land and labor. Nearly two decades later Guatemalans would learn of the brutality of a military regime that would go to any lengths, including genocide against innocent indigenous-Mayan civilians, to suppress the insurgency.

Was this snapshot of two young foot soldiers a sign of what was to come? It is convenient to position these two soldiers as symbols of the violence that ensued in coming decades. But in 1966, terror had not yet reached its apex. The conflict was still, in part, a “gentlemen’s war,” fought between members of the upper and middle classes. At the time, foot soldiers, many of whom came from poor Mayan communities, were unaware of the military operations that would define the ensuing decades. They experienced the same ominous environment of uncertainty that most Guatemalans did.

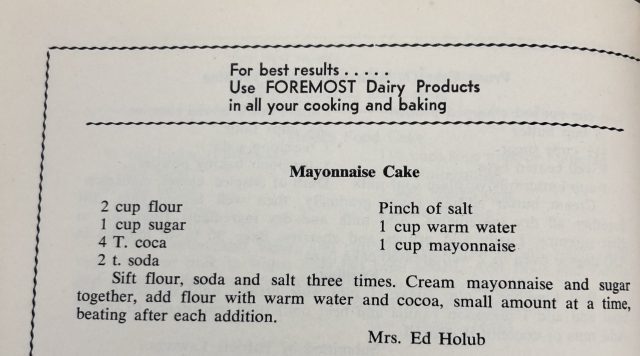

This past February, the author of these photographs, Rupert Chambers, reflected on his work for a public audience at the Benson Latin American Collection and took time to answer my questions. He visited Guatemala in 1966 as a UT graduate student doing historical research. There, Chambers documented the streets and people of Guatemala City and rural towns. He photographed Mayan women at local markets, children selling goods, and funeral processions through the streets. The camera lens captures citizens who continued to make a living, coping through poverty, violence, and discrimination. How do these photographs help us understand the context of the civil war?

As an American in a highly fragile moment in Guatemala, Chambers reflects on the lack of awareness among Americans in Guatemala about the military and political conflict at the time. “They [Guatemalans] knew we [the U.S. Government] had overthrown their revolution in 1954; we had not yet admitted it to ourselves.” He was referring to the CIA administered revolt that replaced Guatemala’s 10-year old democratic government with a right-wing regime.

In 1966, roughly a decade into the Vietnam war, U.S. military advisers were exporting their anti-communist military infrastructure into their neighbor in Central America. Guatemalan generals obligingly received aid in the form of training, as well as technical and material support. The American military also authorized thousands of Guatemalan military commissioners to help combat the perceived communist threat. In the 1980s, the military collaboration was more obvious to American observers. In 1966, however, Americans in Guatemala were still in the dark. Chambers remembered how “few of us were aware of the full extent of U.S. support and intervention.”

An air of uncertainty occupied the minds of ordinary Guatemalans as well. Chambers spoke about this overall atmosphere, pointing out that most Guatemalans were aware of the conflict but not the extent, and no one would have used the term “civil war” at that juncture. “While not exactly the calm before the storm, the mid-1960s gave only clues and portents.”

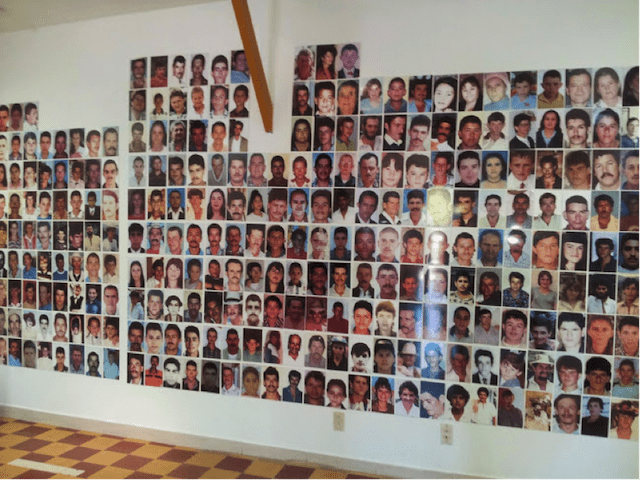

Behind the scenes, networks of right-wing terror groups flowed in the capital city. Signs of terror reared their ugly heads. Chambers described witnessing street signs of the mano blanco (white hand). The “white hand” was a symbol for a clandestine terror organization that used death lists to assassinate democratic leaders and decorated the corpses of their victims with threatening notes. In the 1960s, Guatemala would become one of Latin America’s first settings of “forced disappearances.”

Despite this violent background, Rupert Chambers’ photographs provide an important perspective on the “day-to-day.” As Chambers states, “Guatemalans had lived in a context of violence for so long that in the mid-sixties this all appeared to them as more of the same, a constantly fluctuating level of violence, a cause for concern but not yet something very much out of the ordinary as it was soon to become.”

Chambers prompts historians to consider whether we can we document a tragedy before it happens. Photographer Sally Mann once stated that “photographs open doors into the past, but they also allow a look into the future.” Historians may examine such photographs for clues of terror, silence, and ambiguity. There is something deceptive, however, about looking at these photographs solely through the prism of what was to come; something deterministic. The precariousness of Guatemala’s situation was as much a product of history as it was an unfortunate feature of daily life. And while Guatemalans feared the past and future, their dignity remained in the present.

Photo documentary evidence of state violence also has a history. About a decade after Chambers’ 1966 photographs, a new wave of visual records would help document the violence in Guatemala, spearheaded by the likes of Jean-Marie Simon, in her book Guatemala: Eternal Spring, Eternal Tyranny, and Pamela Yates, in her documentary, When the Mountains Tremble. Such visual documentation propelled human rights efforts to combat the impunity of the Guatemalan state apparatus, which was responsible for around of 90% of civilian deaths during the war.

Chambers’ photographs embodied one of the earlier stages of the documentation of the civil war. His photographs document an underexamined area of history in the ambiguities and fears of daily life under violent regimes. While photography was Chambers’ hobby, he intentionally set out to document human dignity, something he claimed to learn much about from the people of Guatemala. Chambers continues this work in his new project in Mexico.

(All photos here are published with the permission of the photographer.)

An Anticipated Tragedy: Reflections on Brazil’s National Museum by Edward Shore

Black Amateur Photography by Joan Neuberger

Media and Politics from the Prague Spring Archive by Ian Goodale

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.