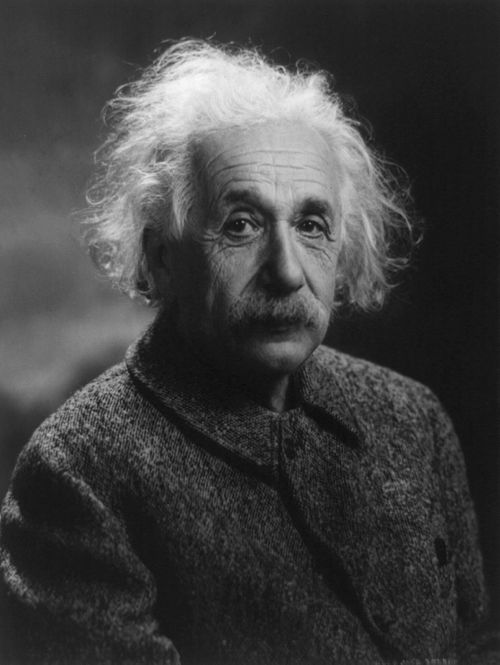

On a mid-July day in 1939, Albert Einstein, still in his slippers, opened the door of his summer cottage in Peconic on the fishtail end of Long Island. There stood his former student and onetime partner in an electromagnetic refrigerator pump, the Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard, and next to him a fellow Hungarian (and fellow physicist), Eugene Wigner. The two had not come to Long Island for a day at the beach with the most famous scientist in the world but on an urgent mission. Germany had stopped the sale of uranium from mines in Czechoslovakia it now controlled. To Szilard, this could mean only one thing: Germany was developing an atomic bomb.

Szilard wanted Einstein to write a letter to his friend, Queen Mother Elisabeth of Belgium. The Belgian Congo was rich in uranium, and Szilard worried that if the Germans got their hands on the ore, they might have all the material they needed to make a weapon of unprecedented power. First, however, he had to explain to Einstein the theory upon which the weapon rested, a chain reaction. “I never thought of that,” an astonished Einstein said. Nor was he willing to write the Queen Mother. Instead, Wigner convinced him to write a note to one of the Belgian cabinet ministers.

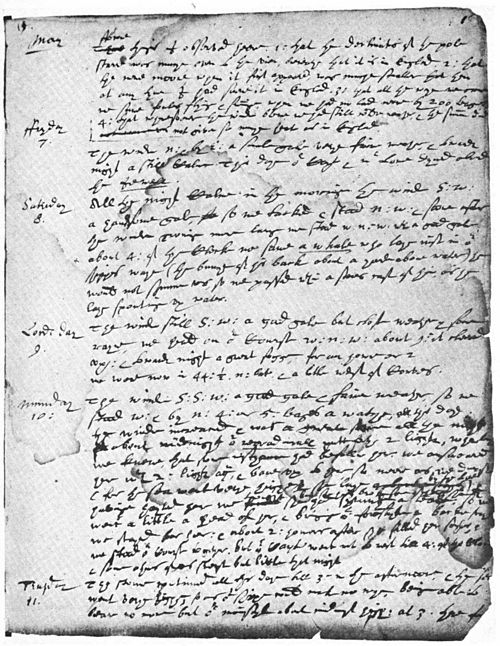

Pen in hand, Wigner recorded what Einstein dictated in German while Szilard listened. The Hungarians returned to New York with the draft, but within days, Szilard received a striking proposal from Alexander Sachs, an advisor to President Franklin Roosevelt. Might Szilard transmit such a letter to Roosevelt? A series of drafts followed, one composed by Szilard as he sat soaking in his bathtub, another after a second visit to Einstein, and two more following discussions with Sachs. Einstein approved the longer version of the last two, dated “August 2, 1939,” and signed it as “A. Einstein” in his tiny scrawl.

Pen in hand, Wigner recorded what Einstein dictated in German while Szilard listened. The Hungarians returned to New York with the draft, but within days, Szilard received a striking proposal from Alexander Sachs, an advisor to President Franklin Roosevelt. Might Szilard transmit such a letter to Roosevelt? A series of drafts followed, one composed by Szilard as he sat soaking in his bathtub, another after a second visit to Einstein, and two more following discussions with Sachs. Einstein approved the longer version of the last two, dated “August 2, 1939,” and signed it as “A. Einstein” in his tiny scrawl.

The result was the “Einstein Letter,” which historians know as the product not of a single hand but of many hands. Regardless of how it was concocted, the letter remains among the most famous documents in the history of atomic weaponry. It is a model of compression, barely two typewritten, double-spaced pages in length. Its language is so simple even a president could understand it. Its tone is deferential, its assertions authoritative but tentative in the manner of scientists who have yet to prove their hypotheses. Its effect was persuasive enough to initiate the steps that led finally to the Manhattan Project and the development of atomic bombs.

Stripped of all jargon, the letter cited the work of an international array of scientists (“Fermi,” “Joliot,” “Szilard” himself), pointed to a novel generator of power (“the element uranium may be turned into a new and important source of energy”), urged vigilance and more (“aspects of the situation call for watchfulness and, if necessary, quick action”), sounded a warning (“extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed”), made a prediction (“a single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with the surrounding territory”), and mapped out a plan (“permanent contact between the Administration and the group of physicists working on chain reactions in America . . . and perhaps obtaining the co-operation of industrial laboratories”). A simple conclusion, no less ominous for its understatement, noted what worried the Hungarians in the first place: “Germany has actually stopped the sale of uranium from the Czechoslovakian mines which she has taken over.”

Looking back at the letter, aware of how things actually turned out, we can appreciate its richness. For one thing, it shows us a world about to pass from existence. Where once scientific information flowed freely across national borders through professional journals, personal letters, and the “manuscripts” to which the letter refers in its first sentence, national governments would now impose a clamp of secrecy on any research that might advance weapons technology. The letter also tells us how little even the most renowned scientists knew at the time. No “chain reaction” had yet been achieved and no reaction-sustaining isotope of uranium had been identified. Thus the assumption was that “a large mass of uranium” would be required to set one in motion. No aircraft had been built that could carry what these scientists expected to be a ponderous nuclear core necessary to make up a bomb, so the letter predicts that a “boat” would be needed to transport it.

Looking back at the letter, aware of how things actually turned out, we can appreciate its richness. For one thing, it shows us a world about to pass from existence. Where once scientific information flowed freely across national borders through professional journals, personal letters, and the “manuscripts” to which the letter refers in its first sentence, national governments would now impose a clamp of secrecy on any research that might advance weapons technology. The letter also tells us how little even the most renowned scientists knew at the time. No “chain reaction” had yet been achieved and no reaction-sustaining isotope of uranium had been identified. Thus the assumption was that “a large mass of uranium” would be required to set one in motion. No aircraft had been built that could carry what these scientists expected to be a ponderous nuclear core necessary to make up a bomb, so the letter predicts that a “boat” would be needed to transport it.

More than the past, the letter points to the shape of things to come. Most immediately, it shows us that the race for atomic arms would be conducted in competition with Germany, soon to become a hostile foreign power. And in the longer term, of course, the postwar arms race would duplicate that deadly competition as hostility between the United States and the Soviet Union led them to amass more and more nuclear weapons. The letter also presents us with nothing less than a master plan for what became the Manhattan Project, the first “crash program” in the history of science. After the war, other crash programs in science—to develop the hydrogen bomb; to conquer polio; to reach the moon; to cure cancer—would follow. Finally, by stressing the entwining of government, science, and industry in service of the state, the letter foreshadows what Dwight Eisenhower later called “the military-industrial complex.”

In the end, the “Einstein Letter” is a document deservedly famous, but not merely for launching the new atomic age. If we read it closely enough, it gives us a fascinating, Janus-faced look at a tipping point in history, a window on a world just passing and one yet to come, all in two pages.

You can read the letter in its entirety here.

Related stories on Not Even Past:

The Normandy Scholar Program on World War II

Review of The Atom Bomb and the Origins of the Cold War

Review of Churchill: A Biography

Review of Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan

Bruce Hunt on the decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan

Photo Credits:

Albert Einstein, 1947, by Oren Jack Turner, The Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

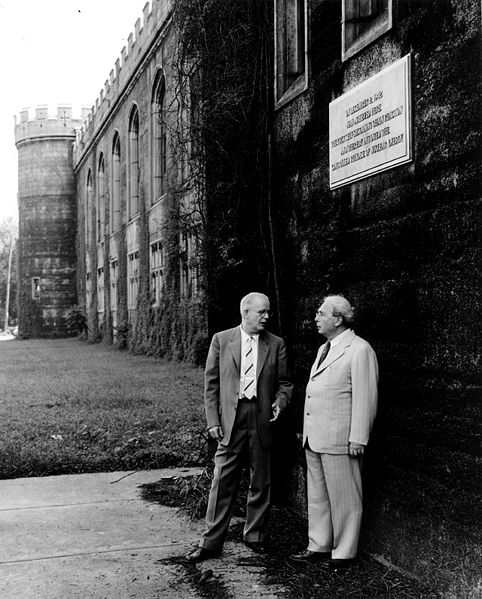

Dr. Norman Hilberry and Dr. Leo Szilard (right) stand beside the site where the world’s first nuclear reactor was built during World War II. Both worked with the late Dr. Enrico Fermi in achieving the first self-sustaining chain reaction in nuclear energy on December 2, 1942, at Stagg Field, University of Chicago. U.S. Department of Energy via Wikimedia Commons

by

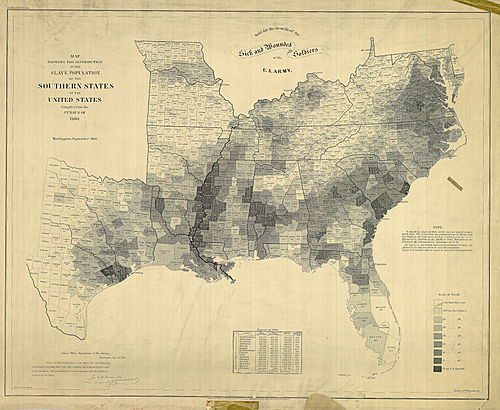

by  Perhaps it is to be expected. Ever since the conflict’s inception, scholars have hotly debated whether, for example, the crisis was precipitated by Southern economic backwardness or Northern economic nationalism; the institution of slavery itself or its possible territorial expansion; a conspiracy of the “Slave Power” or a conspiracy of Northern manufacturers seeking to exploit the agrarian South.

Perhaps it is to be expected. Ever since the conflict’s inception, scholars have hotly debated whether, for example, the crisis was precipitated by Southern economic backwardness or Northern economic nationalism; the institution of slavery itself or its possible territorial expansion; a conspiracy of the “Slave Power” or a conspiracy of Northern manufacturers seeking to exploit the agrarian South. Magness is not alone in recovering the economic remnants of Civil War history. Marc Egnal has made a particularly loud splash with

Magness is not alone in recovering the economic remnants of Civil War history. Marc Egnal has made a particularly loud splash with