On November 18, 2011, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff launched the National Truth Commission (Comissão Nacional da Verdade or, CNV). The CNV’s mandate included the investigation of torture, disappearances, executions, and other human rights abuses committed between 1946 and 1988. The commission’s period of inquiry covered twenty-one years of military rule, from 1964 to 1985.[1] The National Truth Commission began more than two decades after the dictatorship’s end, and this delay makes Brazil one of the last countries in Latin America to undertake a state-sponsored investigation of human rights violations committed during the Cold War.

Source: Isaac Amorim

Brazil, the third country in Latin America to undergo a democratic transition, has lagged behind many of its neighbors in the fight for truth and accountability. This occurred, in part, because of the gradual nature of the transfer of power. The military regime had achieved a relatively successful socioeconomic record and maintained a significant level of societal support. As a result, the armed forces exercised a high degree of control over democratization and successfully negotiated the conditions of this transition.[2]

Among the most substantial concessions won by the military was the 1979 Amnesty Law, which granted pardons for political or related crimes perpetrated between 1961 and 1979. Interpreted broadly since its passage, the 1979 amnesty has guaranteed impunity for state agents who committed human rights abuses. In Memory’s Turn: Reckoning with Dictatorship in Brazil, Rebecca J. Atencio, a professor of Brazilian literary and cultural studies, takes 1979 as democratization’s starting point and traces Brazil’s transitional justice process within a regional context.

The first book to analyze institutional and cultural responses in the aftermath of state terrorism in Brazil, Memory’s Turn (2014) seeks to understand the dynamic relationship between transitional justice mechanisms and exceptional cultural works (literature, television, film, and theater). Atencio’s innovative approach attempts to bridge two distinct fields: memory studies and transitional justice studies. Memory’s Turn asks readers to consider whether activity in one realm affects outcomes in the other. Atencio does not argue there is a causal relationship between artistic-cultural production and institutional mechanisms, but she does contend that interplay between the two realms can “magnify and prolong the impact of both and thereby lay the foundation for further institutional steps.”[3]

Atencio primarily concerns her study with the public reception and framing of cultural works. This emphasis leads her to rely on mass media, scholarly criticism, and published interviews by artistic producers (memoirists, actors, network producers, screenwriters) as well as the cultural works themselves. Although Atencio consulted scholars, creators, and activists during her research, she does not include personal interviews in her analysis. The reliance on published statements reflects her desire to understand how cultural producers framed their works and agendas in public debates.

In order to study the interaction between cultural production and transitional justice, Atencio first selected key institutional measures and then identified “linked” works. She considers cultural and institutional acts linked when they launch around the same time, and the general public begins to associate the two events with one another. This creates what Atencio defines as an “imaginary linkage.” Once the public has paired cultural and institutional mechanisms, individuals or groups can leverage the connection in order to promote their agenda. Atencio refers to this multi-part process as a “cycle of cultural memory.”[4]

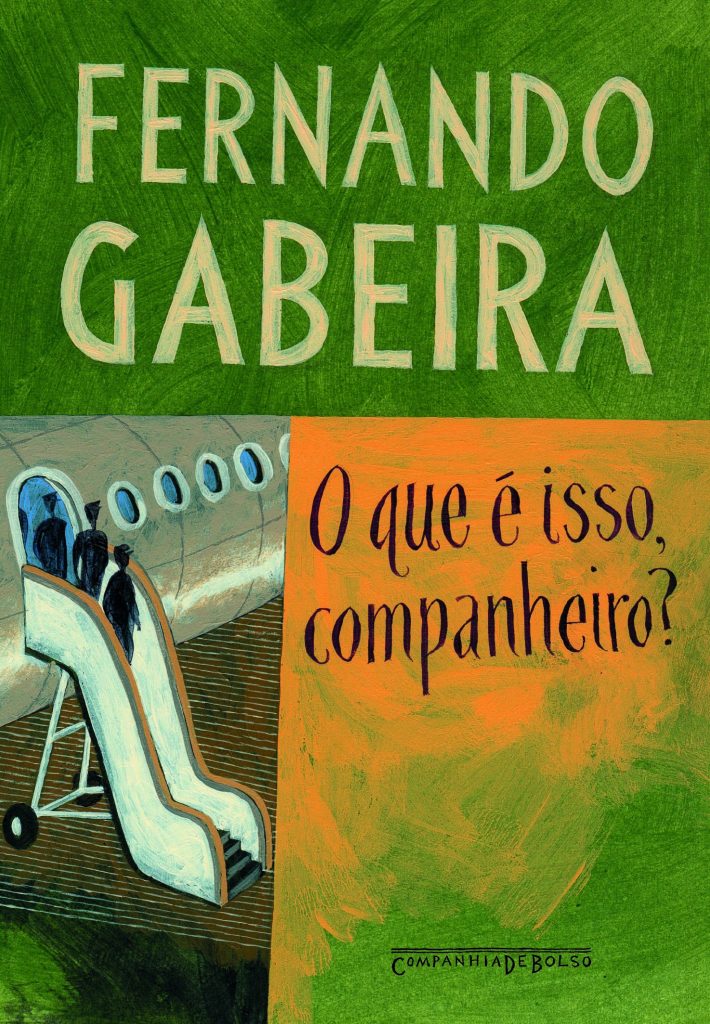

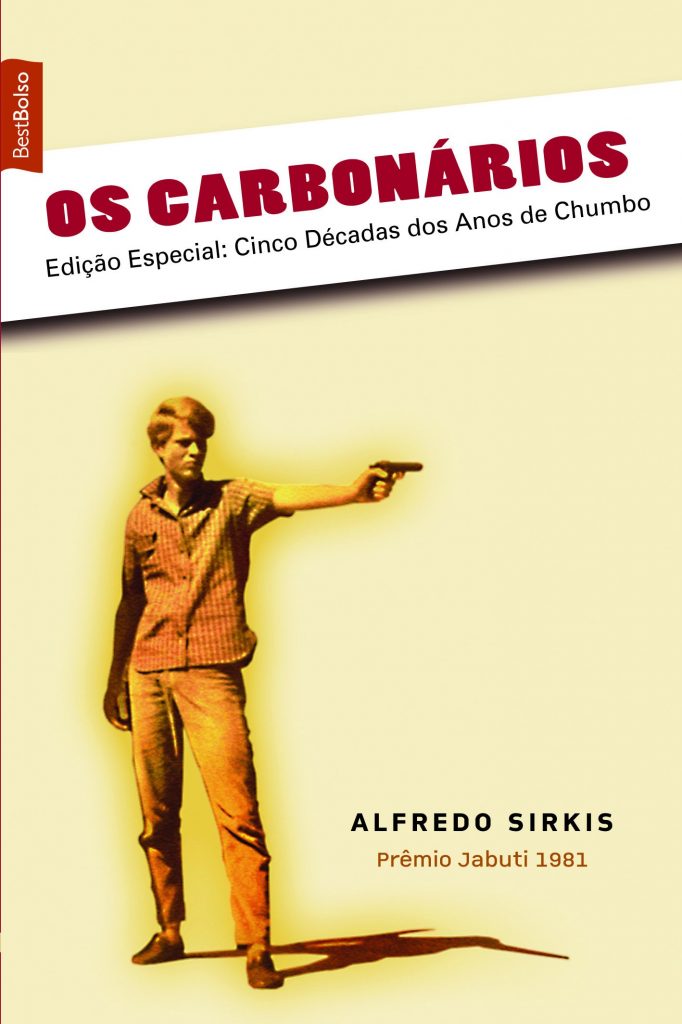

Over four chapters, Memory’s Turn traces four cycles of cultural memory that took place between the 1970s and early 2010s. Not all works that emerge concurrently with an institutional mechanism become paired, so Atencio focuses her analysis on a few exemplary artistic-cultural productions that achieved this imaginary linkage. Chapter one analyzes how Brazil’s Amnesty Law became associated with two memoirs published by former militants: O que é isso, companheiro by Fernando Gabeira and Os carbonários by Alfredo Sirkis. The following chapter explores the television mini-series Anos rebeldes, partially inspired by Sirkis’s memoir. The show coincided with the impeachment process initiated against Fernando Collor de Mello, Brazil’s first-democratically elected president following the dictatorship, and became tied to popular student protests. In chapter three, she examines Fernando Bonassi’s novel Prova contrária in conjunction with the commission formed to award reparations to the families of those disappeared under the military regime. The final chapter investigates the connection between the play Lembrar é resistir and the establishment of Brazil’s first official site of memory at a former torture center in São Paulo.

By evaluating individual cycles of cultural memory, Memory’s Turn moves chronologically from the dictatorship’s end to the present day. Atencio brings these case studies together in her concluding chapter, which analyzes the longer arc of transitional justice and collective memory processes in Brazil within a global context. Ultimately, Atencio concludes that the linkage between cultural works and institutional mechanisms can foster wider public engagement and new efforts to reckon with the past.[5] As a result, cultural producers, along with human rights groups and activists, have led the turn to memory in Brazil and pressured the state to abandon its politics of silence.

Although Brazil’s long period of official silence presents some challenges to transitional justice studies, the Brazilian case emerges as a test case to assess the impact of delayed mechanisms. Unlike its regional counterparts, Brazil has adopted a more gradual approach to reckoning with its authoritarian past. The first institutional measure, a reparations program, did not arrive until ten years after the democratic transition. As trials and memory work continue to progress throughout Latin America, Brazil provides insight into how and why transitional justice approaches change over time. Shifting social and political landscapes influence trajectories and outcomes.

Memory’s Turn traces the evolution of Brazil’s transitional justice process and acknowledges its complexities without treating the Brazilian experience as unusual or exceptional. By placing Brazil within a regional context, Rebecca Atencio offers a unique theoretical insight for transitional justice studies. Memory’s Turn provides scholars a model for conceptualizing the dynamic relationship between legal mechanisms and cultural works in post-conflict societies. Over the long term, Atencio’s theoretical framework will apply to other national and regional contexts and help scholars better understand the long-term impact of transitional justice measures in post-conflict societies.

[1] “Brazilian Truth Commission Has Historic Responsibility,” International Center for Transitional Justice, last modified May 11, 2012, https://www.ictj.org/news/brazilian-truth-commission-has-historic-responsibility.

[2] Zoltan Barany, The Soldier and the Changing State: Building Democratic Armies in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012), 128.

[3] Rebecca J. Atencio, Memory’s Turn: Reckoning with Dictatorship in Brazil, (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2014), 8.

[4] Ibid, 6-8.

[5] Ibid, 125.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.