From the editors: One of the joys of working on Not Even Past is our vast library of amazing content. Below we’ve updated and republished Judith Coffin’s illuminating, powerful and moving article on contraception in France, which was first published in 2012. Given recent developments related to reproductive rights, we feel this article could not be more timely.

In 1967, Radio Luxembourg recruited Menie Grégoire, a well-known journalist and expert on “women’s” issues, to host an audience Q&A program on the airwaves. Radio Luxembourg was a privately-owned radio station; its shows were first produced in Paris and then cabled to and broadcast from Luxembourg. But the program reached deep into France. By 1970, nearly 2.5 million listeners tuned in to listen to Grégoire, and her program displaced the advice-from-experts programs and old-school family radio dramas that Radio Luxembourg had carried since the end of World War Two. Remarkably for historians, Grégoire saved and classified all the letters her listeners sent the program (nearly 100,000 of them), and she took notes on their telephone calls (around 16,000). Those papers are now in the archives of the Indre et Loire, outside of Tours, in France. Historians who want to work in the collection need Grégoire’s permission to do so and they cannot reproduce any of the letters in their entirety or identify any of the correspondents. But the letters offer a remarkable portrait of France in the years before and after 1968, the more unusual for being focused on provincial France rather than Paris.

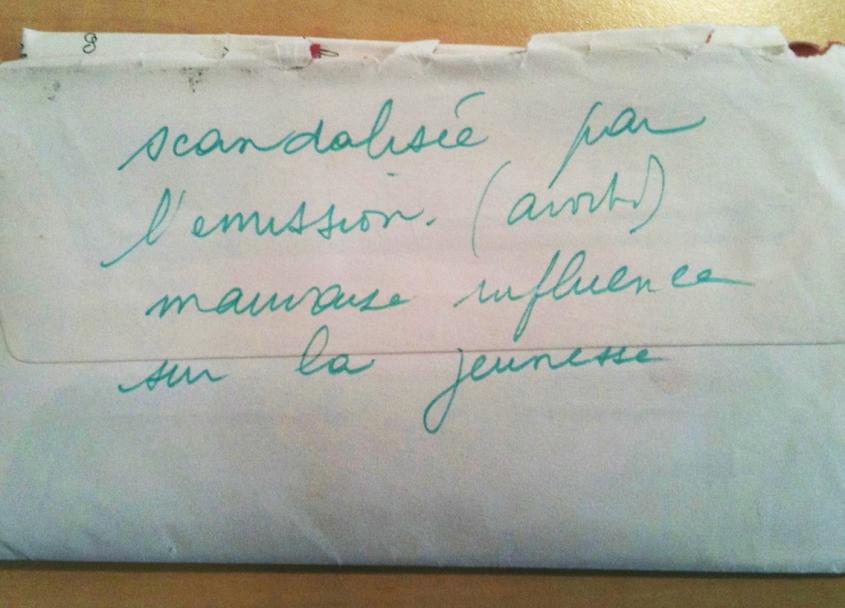

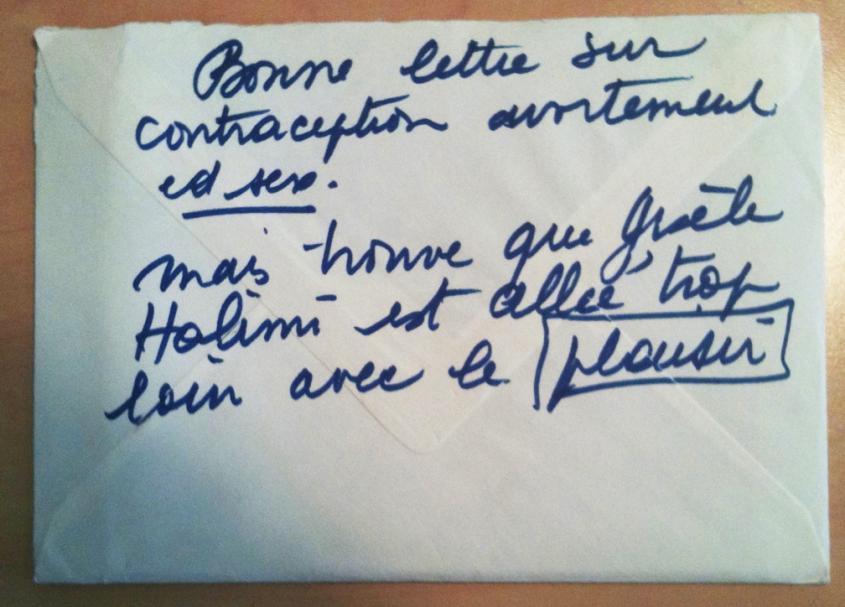

Listeners wanted to discuss any number of issues: work, housing (in short supply as the economy expanded), credit and debt, the struggles of family businesses, and everything having to do with sex. They asked about sexual dilemmas and crises, pregnancy, family life, parents or in-laws (helpful intrusive, or both), and children, but contraception and abortion topped the list of women’s concerns. (Men wrote as well: they, too, were and are implicated in fertility and reproduction.) In 1967, the same year that Grégoire began broadcasting, the Neuwirth law made it legal for the first time, to discuss contraception in public – and cautiously opened the door to approving the sale of selected oral contraceptives, IUDs, and diaphragms. The law had overwhelming public support, but met institutional resistance. The Pope struck back with a papal encyclical reiterating the Church’s opposition to contraception, startling public opinion in France and much of the world, which had expected the Church to soften its position. Some pharmacists refused to fill prescriptions for the pill and some doctors were reluctant to write them. Many women mistrusted “chemical” treatments. “Nature will take its revenge,” warned a French senator who had opposed the bill, stoking fear: “No cycle, no libido, no fantasies . . . breasts so painful that they can’t be touched, and psychic (sic) problems thrown in for good measure. And nature’s first revenge is that the partner becomes less interested [. . .]” (Gauthier 1999: 151).

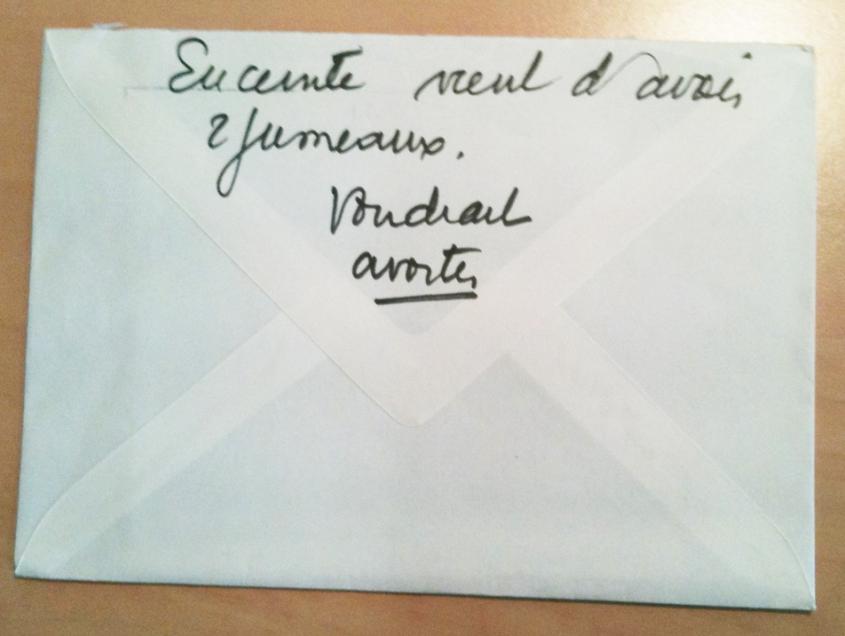

Small wonder that different contraceptive methods and their ramifications loomed so large in the questions listeners sent in to Grégoire’s program. Countless women wrote Grégoire asking where and how they could get a safe and legal abortion – which usually meant going to Switzerland. Grégoire could not provide that information directly, but other listeners often responded by passing on stories of their own experiences. (Abortion would be partially legalized in 1975.)

The letters in the archive testify to women’s fears — of pregnancy, new forms of contraception, their parents, neighbors, or husbands. They also testify to women’s desire for reliable information, to the humiliations of having to depend on doctors for birth control, to the enormous complications that everyday sexual life created and strategies for dealing with them, and to the widespread wish among ordinary women to control their own decisions about reproduction.

February 13th, 1970:

I am 68, and while listening to you talk about contraception, I can’t help but think that these women are lucky – people are paying attention to them and they dare talk. (Fonds Menie Grégoire 66 J 30)

December 12th, 1967:

“Personal” written on the envelope.

Help me.

I am 17 ½ and like all girls I have my problems. My parents bought a pastry shop and café. We are open every day. I have to hurry home after school to work: wash the dishes, tidy the house, do the laundry, mop the floor, etc. My father works all night, and so he sleeps during the afternoon. My parents never have time: they only have work. They get along very well, but this is not a private life, and certainly not a family life.

[. . .] When I was young, if a pregnant woman came into the store my mother always sent me out — to fetch a broom, or something. They have never explained anything to me. Even last week, when the radio was talking about the pill during the news, my mother turned it off . . . . I can see she is afraid of having this conversation and I don’t want to upset her. (66 J 37, 925)

December 12, 1967th:

Letter from a woman 25, who has been married for four years and has a three-year-old girl. That birth was very difficult, and neither she nor her husband wants more children.

[. . .] every month is nothing but fear and anxiety, fear to find myself pregnant for a second time. That’s my life, always worrying about that fear I can’t describe but that gets inside me and makes me look at everything differently. . . . Of course I have heard talk of means of contraception, but I don’t know who to go to. I am ashamed to go to my doctor and tell him my little problems. I’m afraid he’ll make fun of me. (66 J 230)

February 11th, 1974:

Letter from 45-year old woman.

I’m afraid I am pregnant. We have always used withdrawal. But now my husband is having problems, and so sometimes he isn’t careful. I think you’re going to find me old fashioned . . . . But I have to tell you that we have always dealt with doctors who are quite cold, and we haven’t dared raise the subject. (66 J 231)

December 21st, 1967:

Letter from a regular listener. One of countless stories about extra marital pregnancies and how women and men dealt with them.

When I was 15, I ‘frequented’ a boy one year older. I got pregnant. His parents refused to let us marry. So I had my child, and continued to work on my family’s farm. The boy came back, I got pregnant again, and I agreed to marry him. We lived with my parents. Living with my father was nearly impossible. My husband worked in a bakery, where he worked all night. Since I had two children, I had very little time for him. A combination of that and the “scenes” with my family drove him away, leaving me with my two children. For the next five years, I worked as a maid while my grandmother took care of the children. I only got to come home on the weekends to see them.

[. . .] Then I married a man, a widower with 3 children. We have two children together. I didn’t love him at the beginning but I am learning to. Today many people admire me for marrying a man (who I didn’t love). I have put my life back together. (66 J 37, #932)

December 8th, 1967:

Letter from a 30-year-old.

Please send me the list of the books that you provided during your show last Saturday on sexual education and contraception. Send me the publishers too, so I can order them by mail. Can you include the list from the week before? I wrote down “the pill: yes or no,” but I didn’t get the rest down.

Here’s the problem. [. . .]

I am 30. I have been married nine years. Both of our parents were divorced. This was difficult for me, less so for him.

I am shy. I got married. We had our first child, a daughter. A sunny household. [Ménage sans nuage.] Then my health started to fail. I have thyroid problems and irregular periods. [. . .]

In the summer of 1965, fate descended on us. We didn’t want a child and one was coming.

My husband was transformed. He felt betrayed. He closed himself off. . . . I refused all sexual relations. I love him but I am afraid. I gave in once, and when my period was late, I was seized by the darkest fear. It was only my thyroid.

We still have no sexual relations.

I can’t talk about this with my family doctor – he always just wants another baby. When he comes to our house, he asks whether we have “ordered up a little brother for our girls.” I just stand there. I don’t know how to answer him. (66 J 40, #1805)

July 17th, 1971:

Letter from 27 year old, responding to another young woman’s story on Grégoire’s program.

I don’t know how to tell you about this, I’ve never spoken about it (except to my husband).

I got pregnant just before we were married. We went to a doctor who gave me a shot to bring back my period [these were hormone shots], and nothing happened, I was pregnant. Horrible.

[She was the third of five girls, she said. She couldn’t tell her parents.]

My mother has a lot of principles (for her, an unwed mother ‘une fille mere’ is a bitch ‘une chienne’) and she calls herself a Christian. My father is very strict. Everyone knows him in the village, and everyone likes him, but he is completely rigid with his family. When I was working, I wasn’t allowed to go out at night. [. . .]

I had an abortion. That cost us 100,000 francs. I was incredibly lucky to have an elderly nurse who didn’t massacre me. Then I had a D and C.

After that, I used a diaphragm for three years. Then I had a baby.

I hope my child will have a different experience. (66 J 22)

July 5th, 1971:

Letter from a school teacher, married for three years to another school teacher, who is just finishing his military service. She refuses to describe herself in the clichéd terms of women’s magazines. She isn’t “a woman disappointed by marriage” and her husband isn’t “cheating.”

You give such good advice on the radio that I don’t hesitate to write you to tell you my problem.

[. . .] I’m pregnant again and my second baby is going to be born just about a year after the first. [. . .]

I know that lots of women “manage” [‘débrouillent’] as we say, to get rid of a pregnancy that they don’t want. But aren’t they worried about their own lives? I only see one solution – legal abortion done by a doctor, but — where do you go? Who can give you information? There’s a lot of talk about the subject these days, but even so, I think that it is hard for you to find an address for me. I thought about Switzerland. Do you think you could find at least some information? I am only two months pregnant, and I want to do something now. (66 J 228)

May 5th, 1971:

Letter from a woman, 25, married for 7 years. She is unapologetic and angry, and her husband shares her feelings.

I’m writing you about abortion. I am Catholic, though not practicing. So you understand that I would be against, if my case were not so complicated.

I am five months pregnant with my fifth child, and the oldest will be seven years old at the end of the year. I can tell you, if I had been able to find a doctor who would have accepted to give an abortion the right way, I would have been fully willing, despite my principles. But in France there is no possibility, except clandestine and dangerous.

You are going to say that I could have controlled these births. Of course! I took the pill for 18 months, and then something was irregular and I went eight days without taking it and thought I was protected, which only helped me get pregnant.

So I am for abortion in certain cases, though only if under medical supervision. I hope that these Messieurs who make laws will think. I am strong and helped by my husband, and he helps hold me up, but how many other women. [. . .] (66 J 228)

This article is connected to but does not draw from my recent book, Sex, Love, and Letters: Writing Simone de Beauvoir. For more on that book, see

https://notevenpast.org/an-intimate-history-of-the-twentieth-century/

https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9781501750540/sex-love-and-letters/

Recent works on the history of sexuality in Europe and the US:

Beth Bailey, “Sexual Revolution(s)” in The Sixties: From Memory to History, edited by David Farber (1994).

George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture and the making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (1994).

Hera Cook, The Long Sexual Revolution: English Women, Sex, and Contraception 1800-1975 (2004).

Stephanie Coontz, A Strange Stirring: The Feminine Mystique and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960s (2011).

Kate Fisher and Simon Szreter, Sex Before the Sexual Revolution: Intimate Life in England 1918-1963 (2010).

Elaine Tyler May, America and The Pill: A History of Promise, Peril, and Liberation (2010).

![An image from "Flora Huayaquilensis," a visual collection of South America's plants as seen by Spanish botanist Juan José Tafalla during a 1785 expedition through Peru and Chile. ([Juan Tafalla], “Flora Huayaquilensis,” ourheritage.ac.nz | OUR Heritage - See more at: http://otago.ourheritage.ac.nz/items/show/7696#sthash.r8R9WHhx.dpuf)](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/87bbce75b1706f7ba39ef9bcbb7c9560.jpg)