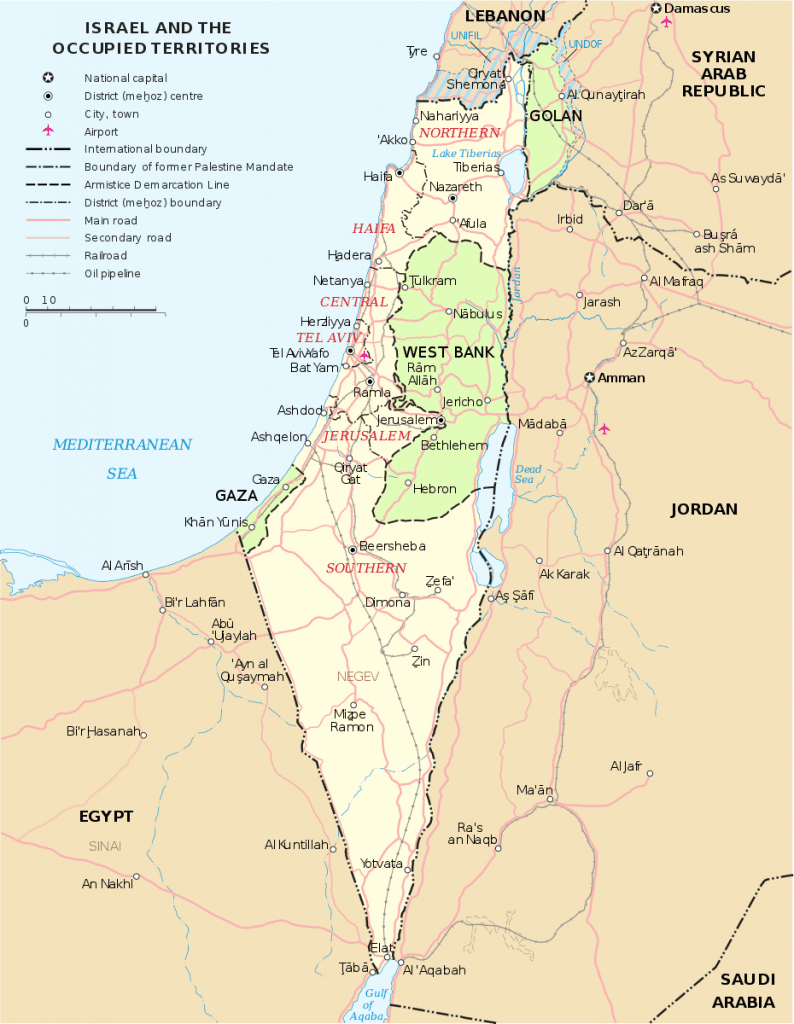

Map of Israel (via Wikimedia)

(UT History faculty come from all over the world. Here are their stories.)

I wish I could introduce clarity, coherence and a sense of purpose into the story of my arrival to this country from my native city of Jerusalem. I wish I could say that it was meticulously planned and well-executed. That it was a clean break with a past life that no longer resonated with me and that leaving behind parents, family, friends and memories was the natural and logical thing to do. I wish I could say that upon my arrival I actually knew English well enough and that it was all easy as it meant to be. That it was like in the movies. But, alas, I cannot. I never really pondered living here and America was never on my family’s radar. We were Europhiles of Italian stock. We did not travel to the US, we did not talk about the US or think about the US. Quite simply, it was not a part of our imagination. And though rock music was the soundtrack of my teenage years, the county as a whole stayed foreign to me.

That remained the case until I discovered the American life of the mind. Until I realized the brilliance of its academy, the beauty of its books and the depths of its intellectual tradition. Until I realized that it is not only Bob Dylan who was out there singing all by himself. And so, in late 1999, when I packed my bags to leave for Princeton I did not really immigrate to a new country with big cities, mighty rivers, unbelievable storms, manicured gardens and bad food. Instead, I immigrated to a new language, a new intellectual landscape and a new sense of perception. Above all else, that became my new home. It still is.

Life in the new country proved to be a mess. My manners were off. I was too rude, too direct, too disrespectful, too aggressive, too casual and too whatever you can imagine as improper and inadequate. The art of “small talk” eluded me. I could not follow the rules. The police took my driver’s license. By the end of four years, I badly wanted to go home, back to the tribal society of Israel where I could once again make sense of myself. A place where you earn points for being rude, direct and truthful and when you don’t need to drink a beer in order to open up your heart. So I did. I married an American girl and moved back home; subconsciously making it as likely as I could that my life in Israel would come to a quick end. And it did. For a while, I celebrated my reunification with the beloved Hebrew language and with its brilliant humor. I indulged in friends, memories, good food and music. A lot of music. But I was also shocked by what I encountered.

The Second Intifada just ended. I mourned the death and destruction. I took the collapse of the Peace Process personally and I hated, and still do, the occupation of Palestinians with every cell of my body. I became an activist and spent more time in threatened Palestinian communities than writing my book. Troubled and upset, the life of the mind was slowly slipping away from me. The politics of getting a teaching position in Israeli academia were something like an episode of the “Game of Thrones.” It was not for me. Months after my return, the prospects of making a life in Israel and building my career there appeared to be slim to non-existent. The fact that my wife was living in Damascus did not help matters, either. I guess this is what Philosopher Svetlana Boym meant when she wrote of the impossible condition of “homesickness and the sickness of home.” It was not good. My parents were also worried, loved ones tried to intervene and friends protested my activism. They wanted me to stop trying to fix the unfixable and settle down. I could see their point, and thought they were right, but I decided to do this settling down somewhere else: in Texas, to be precise. I loved them all, I still do, but that was it. Defying my provincial expectations, UT presented a rich intellectual –and more important – human environment. Fifteen years or so after my crash landing on this campus, it appears that my second coming to America was something of a rebirth. I love it here. Teaching, writing and raising kids is enough for me. I still miss home. I miss it daily, but I have acquired another one as well. It is a home I grew to appreciate and love slowly and patiently, taking it, just as my three daughters do, one step at a time.

Also in this series: