During the summer of 2016, we will be bringing together our previously published articles, book reviews, and podcasts on key themes and periods in the history of the USA. Each grouping is designed to correspond to the core areas of the US History Survey Courses taken by undergraduate students at the University of Texas at Austin.

We start with two posts by Mark Atwood Lawrence on messages sent by George F. Kennan, a senior U.S. diplomat based in Moscow, and Nikolai Vasilovich Novikov, the Soviet ambassador in Washington, outlining their views on the intention of each nation in 1946. These sources and much more come from one of our featured books, America in the World: A History in Documents from the War with Spain to the War on Terror.

As the US and Soviet Union gathered information on each other, spies and bugs became key, as Brian Selman shows in his article on the bug problem at the US embassy in Moscow: Call Pest Control.

During World War II the United States shipped an enormous amount of aid to the Soviet Union through the Lend-Lease program, a program the Russians minimized and the West exaggerated during the Cold War. This is discussed on NEP by Charters Wynn. And here is a video to accompany the piece.

Cali Slair examines documents pertaining to the global attempts to eradicate Smallpox, and highlights the stockpiling of the virus by the US and Soviet Union during Cold War.

In the US, there were fears that hybrid corn would sow the seeds of Communism in the United States, as Josephine Hill reveals in her discussion of the cartoonist Daniel Robert Fitzpatrick.

Charlotte Canning traces the diplomatic role played by US theatre during the first half of the twentieth century.

Mary C. Neuburger discusses the history of US tobacco company’s importing cigarettes into the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War and her book Balkan Smoke: Tobacco and the Making of Modern Bulgaria.

“Before 1948, the Cold War was largely confined to Europe and the Middle East, areas that both U.S. and Soviet leaders considered vital to their nations’ core foreign policy objectives after the Second World War. By 1950, however, the Cold War had spread to Asia.” Mark Atwood Lawrence explains in his article CIA Study: “Consequences to the US of Communist Domination of Mainland Southeast Asia,” October 13, 1950

R. Joseph Parrott takes us to Cold War Mozambique and connections between Eduardo Mondlane, the first president of the Mozambique Liberation Front (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique or FRELIMO) and the US.

And, he looks back at America’s Pro-Apartheid Cold War Past.

Finally, Andrew Straw shares the story of his mother’s trip to Moscow in preparation for the 1980s Olympics.

From the LBJ Archives:

Jonathan C. Brown discusses a rare phone call between Lyndon Baines Johnson and Panamanian President Roberto F. Chiari.

Elizabeth Fullerton discovers documents pertaining to the mysterious destruction of a US aircraft in Turkey in 1965 held in the Papers of Lyndon Baines Johnson.

And, Deirdre Smith examines documents that give a first-hand impression of the nature and texture of relations between the United States and Yugoslavia as it proceeded through the 1960s.

On 15 Minute History:

America and the Beginnings of the Cold War

The Cold War dominated international politics for four and a half decades from 1945-1989, and was defined by a rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union that threatened—literally—to destroy the world. How did two nations that had been allies during World War II turn on each other so completely? And how did the United States, which had been only a marginal player in world politics before the war, come to view itself as a superpower?

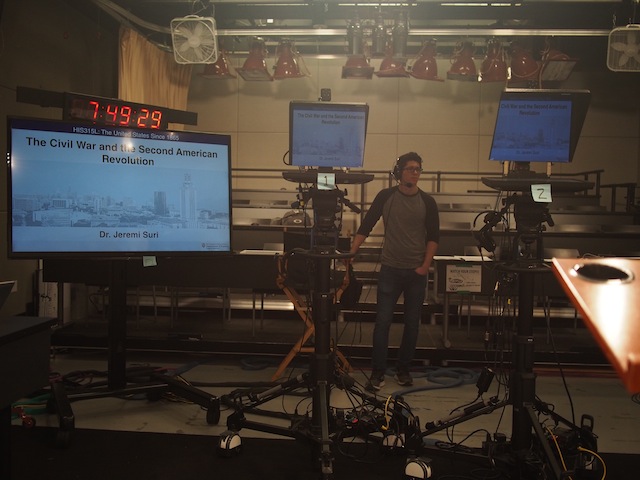

In this episode, historian Jeremi Suri discusses the beginnings of the Cold War (1945-1989) its origins in the “unfinished business” of World War II, the role of the development of atomic weapons and espionage, and the ways that it changed the United States in just five short years between 1945 and 1950.

Operation Intercept

At 2:30 pm on Saturday September 21 1969, US president Richard Nixon announced ‘the largest peacetime search and seizure operation in history.’ Intended to stem the flow of marijuana into the United States from Mexico, the three-week operation resulted in a near shut down of all traffic across the border and was later referred to by Mexico’s foreign minister as the lowest point in his career.

Guest James Martin from UT’s Department of History describes the motivations for President Nixon’s historic unilateral reaction and how it affected both Americans as well as our ally across the southern border.

Energy Crisis of the 1970s

Most Americans probably associate the 1973 oil crisis with long lines at their neighborhood gas stations, but those lines were caused by a complex patchwork of international relationships and negotiations that stretched around the globe.

Guest Chris Dietrich explains the origins of the energy crisis and the ways it shifted international relations in its wake.

Recommended Reading and Films:

At home:

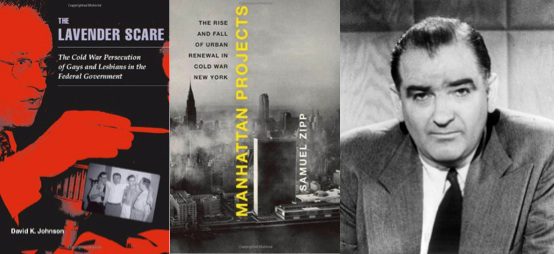

R. Joseph Parrott recommends The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government, by David K. Johnson (University of Chicago Press, 2006).

Kyle Shelton reviews, Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Cold War New York, by Samuel Zipp (Oxford University Press, 2010).

And, Dolph Briscoe IV recommends Clint Eastwood’s J. Edgar (2011)

Cold War Politics on the International Stage:

Yana Skorobogatov reviews The Atomic Bomb and the Origins of the Cold War, by Campbell Craig and Sergey Radchenko (Yale University Press, 2008)

David A. Conrad suggests Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan, by Tsuyoshi Hasegawa (Belknap Press, 2006)

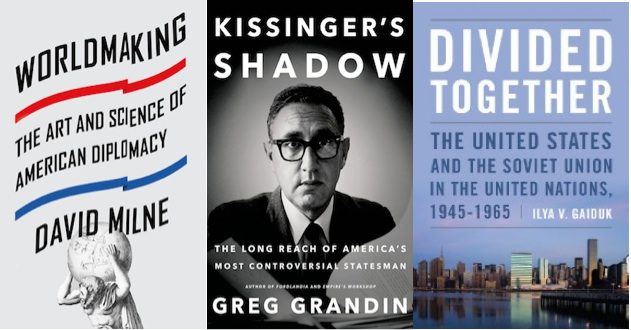

Michelle Reeves recommends Divided Together: The United States and the Soviet Union in the United Nations, 1945-1965, by Ilya Gaiduk (Stanford University Press, 2013) and For the Soul of Mankind: The United States, the Soviet Union, and the Cold War by Melvyn P. Leffler (Hill and Wang, 2008).

Clay Katsky recommends Kissinger’s Shadow, by Greg Grandin (Metropolitan Books, 2015)

If you are interested in US diplomacy during the Cold War see Mark Battjes‘s review of Worldmaking: The Art and Science of American Diplomacy, by David Milne (Macmillan, 2015).

For a gripping history of the Cold War’s final years Jonathan Hunt recommends The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and Its Dangerous Legacy, by David E. Hoffman (Anchor, 2009).

R. Joseph Parrott reviews The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan: A History of the End of the Cold War, by James Mann (Penguin, 2010)

President Reagan meeting with Soviet General Secretary Gorbachev for the first time during the Geneva Summit in Switzerland, 1985 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Cold War around the World:

Kazushi Minami suggests Cold War Crucible: The Korean Conflict and the Postwar World, by Hajimu Masuda (Harvard University Press, 2015)

Michelle Reeves discusses Hal Brands’ argument about US influence in Cold War Latin America (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Aragorn Storm Miller recommends Sad and Luminous Days: Cuba’s Struggle with the Superpowers after the Missile Crisis, by James G. Blight & Philip Brenner (Rowman and Littlefield, 2002).

Yana Skorobogatov on Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959-1976, by Piero Gleijeses (University of North Carolina Press, 2002)

Toyin Falola shares some Great Books on Africa and the U.S, including Thomas Borstelmann, Apartheid’s Reluctant Uncle: The United States and Southern Africa in the Early Cold War (Oxford University Press, 1993).

And finally, John Lisle takes us even further afield, into space, in his review of This New Ocean: The Story of the First Space Age, by William Burrows (Random House, 1998).