By Jesse Ritner

The Trinity test, a proposed starting point for the Anthropocene (via Wikipedia)

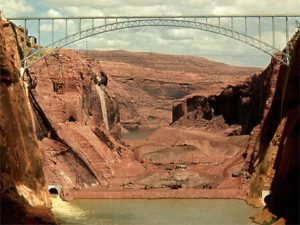

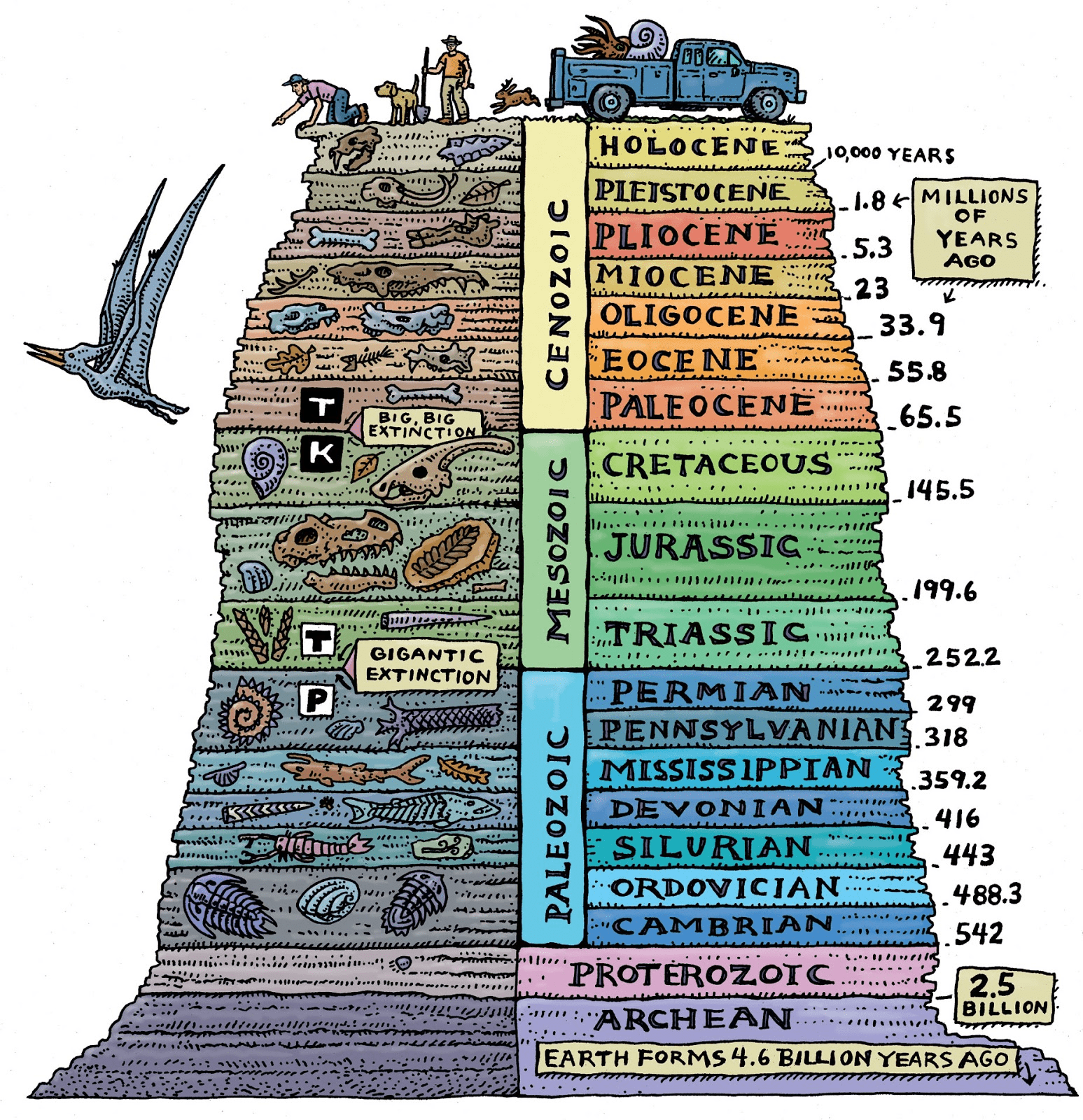

If you open a textbook on geology and flip through to the chapter on geological time it will tell you we are currently living in the epoch of the Holocene. The Holocene started approximately 10,000 years before present with the end of the last ice age. However, research by a diverse array of scientists, who specialize in geology, climate, historical ecology, archeology, and a host of other fields, have begun to question whether or not human impacts on climate mean that we have entered a new epoch in geological time. They call this new epoch the Anthropocene.

The concept of the Anthropocene is on one level quite simple. It is based in part on the science of climate change, which has quite convincingly shown that human activity is the most important driver of global warming. However, the science itself is quite complicated. The problem is that it is impossible to study historic changes in climate in of itself. Instead, scientists use proxies, such as methane or carbon dioxide concentrations in ice cores to measure greenhouses gases, pollen and charcoal in lake cores to measure ecological change and fire frequency, deuterium isotopes to estimate temperature, and a host of other proxies to try and trace how things like greenhouses gases have increased or decreased over time. In of itself, this is fairly routine, although by no means simple, work.

Another problem is that the concept of the Anthropocene is dependent on the idea of the human species as the ultimate driver of climate change. As such, scientists often have to work with archeologists or historians to discover if there is a corollary human action that may cause the climate anomaly they discover through their proxies. Proving these correlations is quite difficult, and often involves people with a number of specialties in order to account for long lists of variables. While radioactive dust dated to 1945 has a clear human cause in the dropping of nuclear bombs, other connections are harder to prove. As scientists look further back in time for earlier and earlier human impacts thousands of years ago, historical and archeological evidence becomes scarcer, making it more difficult to correlate climate change with human action.

(For a short video on the Anthropocene click here!)

Despite an immense increase in studies over the past two decades, scientists have been slow to officially adopt the Anthropocene as a new epoch. Difficulty in determining a starting point is perhaps the most famous objection, but concerns about human agency, anthropocentrism, and the validity of the proxies have caused some scientists to question the utility of the designation.

A Depiction of Epochs and Periods as Understood Through Geological Time Scales ( via Earth Environments)

Despite debate within the scientific community, the Anthropocene as a discourse has taken on a life of its own among humanists and social scientists. Their engagements can be split into three camps: those concerned with defining the Anthropocene, those concerned with the political ramifications, and those concerned the ethical relationship between nature and humans. For instance, historian John McNeill has written about the history of the great acceleration, its human causes, and how energy systems which result in high carbon emissions became standard. Others, like Dipesh Chakrabarty (also a historian), raise questions about the implications for contemporary politics if we begin to think of humans as a species, when humans do not all have equal impacts on climate. Issues of race, class, gender, and histories of capitalism and imperialism are all at risk of being overlooked by discussions about species level solutions to Anthropocene problems. Lastly, philosophers like Donna Haraway have critiqued the anthropocentrism of the idea that humans are just now changing climate. Haraway argues for what she calls the Chthulucene, a world in which humans begin to understand themselves as a part of nature, rather than outside of it. For better or worse, the Anthropocene is now unavoidable in conversations about the environment.

For historians in particular, the Anthropocene demands an integration of climatic and ecological change with the cultural, social, and political changes historians already study. This idea is not totally new. Classic works of environmental history, such as Alfred Crosby’s Columbian Exchange and William Cronon’s Changes in the Land, both written decades before the Anthropocene existed as a concept, examine the historical effect of people on environments and the relationship between people and nature historically. But, ideas connected with the Anthropocene have caused a resurgence of historical work on the environment. Recent books such as James Scott’s Against the Grain and Christophe Bonneuil and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz’s The Shock of the Anthropocene explore how historians can contribute to discussions about the Anthropocene, both in placing its origin, in critiquing its anthropocentrism, in studying the differential impacts of humans on the environment, and in reverse, the impact of the environment on humans.

At Not Even Past, we want to help people work through these complicated questions. So here we are offering a growing list of book reviews and articles related to the environment and the Anthropocene. We hope this brief introduction, and the list below, can act as a resource for teachers looking to build curriculum on environmental histories, while also providing an easy and accessible portal for curious readers to scholarly debates regarding history and the environment.

Books on Environmental History

Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England, by William Cronon (1983)

Crimes against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation, by Karl Jacoby (2003)

Banana Cultures: Agriculture, Consumption & Environmental Change in Honduras and the United States by John Soluri (2005)

Fordlandia by Greg Grandin (2010)

The Deepest Wounds: A Labor and Environmental History of Sugar in Northeast Brazil by Thomas D. Rogers (2010)

The Republic of Nature by Mark Fiege (2012)

The Shock of the Anthropocene: The Earth, History and Us by Christophe Bonneuil and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz (2015)

City in a Garden: Environmental Transformations and Racial Justice in Twentieth-Century Austin, Texas by Andrew M. Busch (2017)

Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States by James C. Scott (2017)

A Primer for Teaching Environmental History: Ten Design Principles. By Emily Wakild and Michelle K. Berry (2018)

Articles on Environmental History

Oil and Gas Drilling in the Gulf of Mexico

Boomtown, USA: An Historical Look at Fracking

Climate Change in History

The Public Historian: Quilombola Seeds

//www.youtube.com/watch?v=J6nMulSoBvw&feature=youtu.be