By Anuj Kaushal

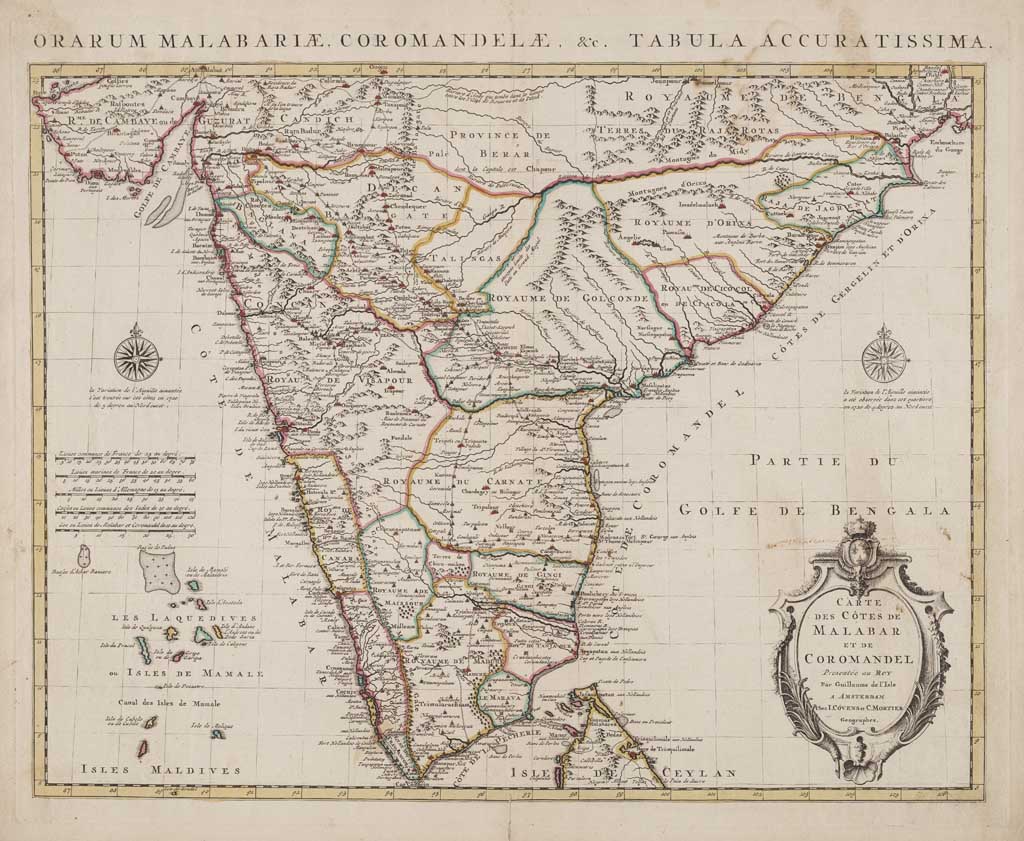

Here Sebastian R. Prange is interviewed about his 2018 book, Monsoon Islam: Trade & Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast (Cambridge 2018), by Anuj Kaushal, a PhD candidate in History at the University of Texas at Austin. Sebastian R. Prange is Associate Professor of South Asian history at the University of British Columbia. He obtained his doctorate from the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies in 2008 and has since held academic appointments in Canada, the United States, and Germany. His first book Monsoon Islam: Trade & Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast (Cambridge 2018) has been awarded both the John F. Richards Prize in South Asian History and the American Historical Association–Pacific Coast Branch Book Award. Its Malayalam translation is forthcoming with Other Books (Kozhikode). The following is a the transcript of an extended interview between Dr Prange and Anuj Kaushal.

Anuj Kaushal is a PhD candidate in History at the University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses upon Islamicate healing practices and traditional medical science in South Asia. His work seeks to study identity formation and gender relations in South Asia through medical print culture, private consumption habits, and pluralistic approach to sexology during the 19th-20th century.

Q. Your book’s title, Monsoon Islam, is a key intervention in the study of Islamic “discursive traditions.” While Monsoon Islam challenges the new orientalist conception of Islam as a monolithic entity, it also provides the opportunity to learn more about diverse cultural influences over Islam. Could you briefly elaborate upon this essence of “Monsoon Islam” that allow readers to better understand Islamic pluralism or what Talal Asad calls the “discursive traditions” of Islam?

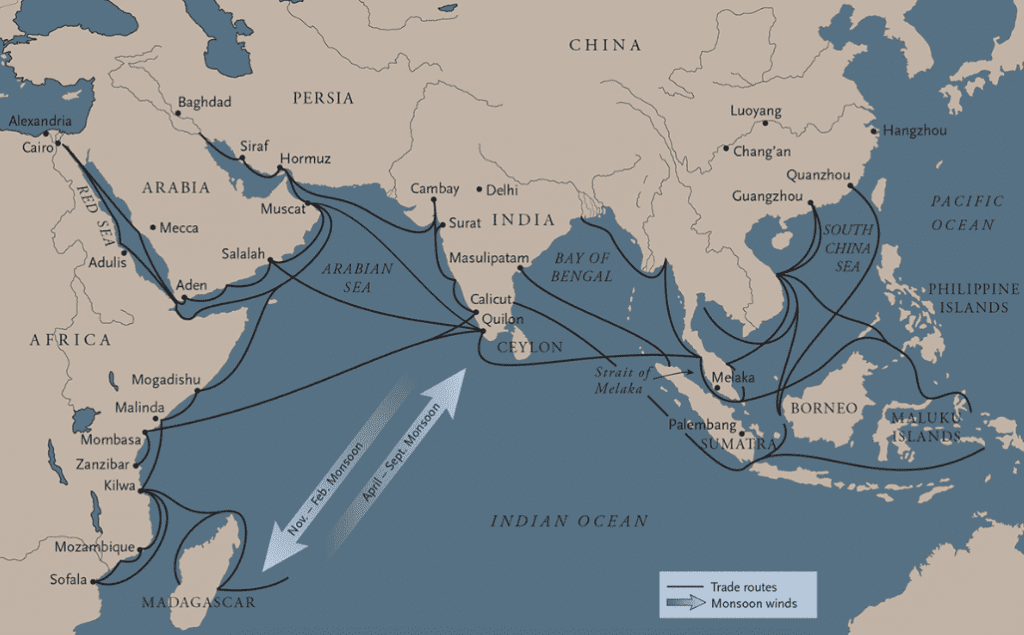

In the book, I use the term “Monsoon Islam” to describe what I see as a distinct trajectory of Islamic history that developed within the trading world of the medieval Indian Ocean. To be clear, it is not meant to denote a formal school of law or a distinct theology; rather, it encapsulates interrelated sets of legal interpretation and socio-religious practices that took shape among Muslim merchant communities in the trading ports of the Indian Ocean. The commercial context is crucial: merchants were key in the formation and transmission of this Monsoon Islam across maritime Asia. The role of trade in the so-called “spread of Islam” has long been acknowledged, but the literature has tended to regard traders as mere conveyances, rather than recognize them as creative agents in communicating and elaborating the faith within new settings. In the Indian Ocean world, Muslim merchants lived in close and sustained contact with non-Muslim societies; in these diaspora contexts, they were continually confronted with new situations for which the standard texts of Islamic law offered no clear course of appropriate action. So in many cases, such as on the Malabar Coast for example, these merchant communities produced new collections of legal interpretation and guidance that addressed the kind of issues that they faced there. As might be expected, most of these have to do with commercial law, but they also engage with questions of cohabitation, commensality, intermarriage, and many other social and political matters that reflected the concerns of Muslims living as part of a majority non-Muslim society. And these interpretations were then taken up by other Muslim communities in other parts of the Indian Ocean world, especially in Southeast Asia. My work reinforces a vision of Islamic history in which there wasn’t a linear transmission of a uniform religion to different places but rather a circulatory process by which the faith came to be translated and reframed in new settings and contexts. As you rightly say, anthropologists such as Asad have long pointed to processes of localization and vernacularization within Islam; my book seeks to offer an additional perspective on this, together with new empirical support, for the medieval period.

Q. Your work analyzes the dynamism of Islam through a “twin process” of meaning making in distinct regions across the Indian Ocean. What are these processes?

The book argues that “Monsoon Islam” was shaped by two intertwined processes. On the one hand, Islam was introduced into new regions by merchants (accompanied by scholars and sufis, who operated within this transoceanic commercial milieu) and influenced by their often quite pragmatic priorities and preferences. On the other hand, the reality of these Muslim merchants living as trading diasporas within majority non-Muslim societies also significantly shaped how Islam was conceived and conveyed in those places. “Monsoon Islam” was defined by the tension between these two forces: between the global and the local, between the competing impulses and imperatives of severalty and syncretism. The book explores this twin process from a dual perspective: it looks both outwards, from the Malabar Coast towards the movements of Muslim communities across the Indian Ocean in space and time, and inwards, to ask how these communities understood and responded to changes in their local, social, and political environments. It does so through the lens of four different spaces that defined the existence of Malabar’s Muslim trading communities:

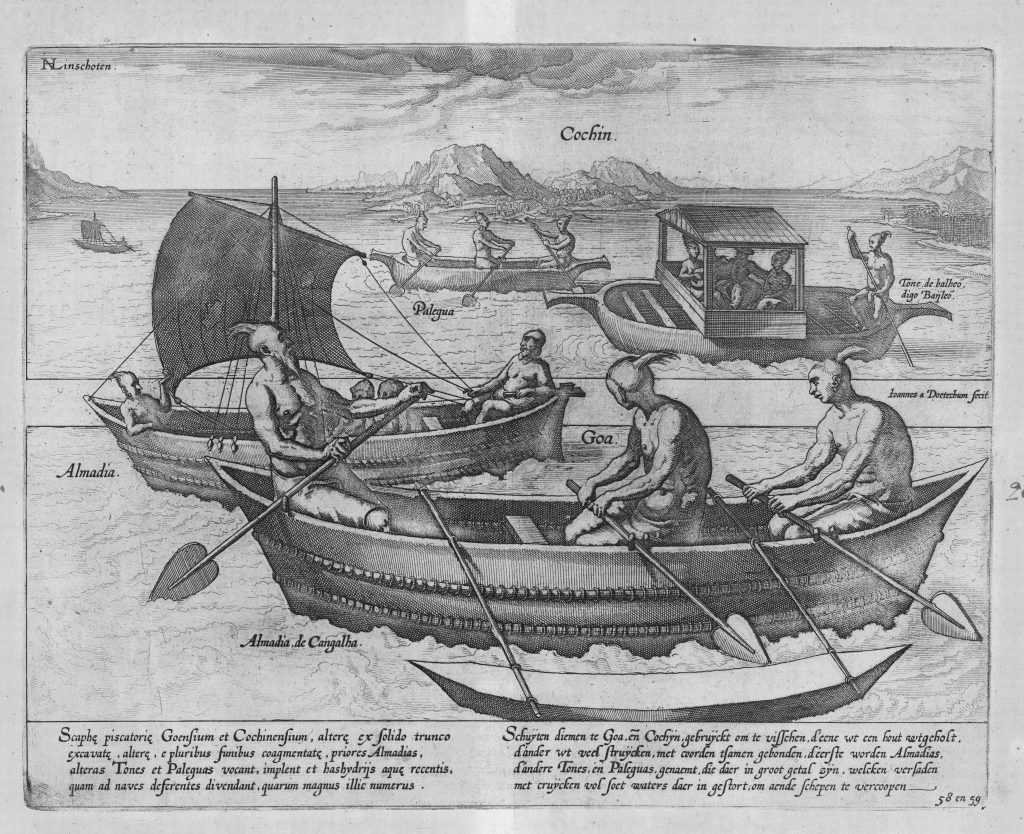

- the Port, which offers an economic history of the practical organization of long- distance trade in the medieval Indian Ocean);

- the Mosque, which examines the internal stratification and social organization of these Muslim trading communities;

- the Palace, which looks at their political relationships to South Indian states and elites;

- and lastly the Sea, which traces the trans-oceanic networks of the pepper trade, religious and scholarly ties, as well as political patronage.

It is the entanglement of all these four realms—the commercial, the social, the political, and the trans-oceanic—that shaped the formation of Muslim communities, and of Islam, across the trading world of the medieval Indian Ocean.

Q. Your book emphasizes trans-oceanic exchanges through networks and actors operating at different levels and in different environments across the Indian Ocean. Could you elaborate upon your methodology through which you analyzed these actors and networks or the role of the brokers in developing this “trans-oceanic network”?

There is no question that network theory has become the dominant paradigm of Indian Ocean studies. The study of networks has underpinned the view of the premodern Indian Ocean as an integrated world system (even if that particular term has fallen out of favor), but it also throws up its own set of core-periphery questions. Within networks, cores are often defined in terms of origins, be it of a kinship group, religious tradition, or trade good. However, as the network expands and evolves over time, its center of gravity also shifts. The spread of Islam, a seminal process in Indian Ocean history, is a prime example of this, but we can also look to Buddhism, or Christianity, or any number of other instances. The actual connections that produced such trans-oceanic milieus of shared cultural ties between distant regions have come to be almost universally described in terms of networks. My book is no exception to this, but I’m also aware that we easily run the risk of reifying every form of contact as a network. Clearly, the network paradigm is as much a product of our present-day worldview as it is of the historical record: in the digital age, even premodern linkages have come to be conceived through the metaphors of circuits, hubs, and nodes.

Where it gets interesting, to my mind, is when we look at how different types of exchange intersect and overlap to create persistent ties. What my book focuses on primarily is the role of long-distance trade as the facilitator of other forms of communication and exchange. Commercial networks were tightly interwoven with kinship, religious, and scholarly networks: Buddhist temples were situated on trade routes; scholarly prestige was established through association with a teacher on the other side of the ocean; pilgrimage was inseparable from economic activity; religious specialists often had an eye for profitable business; and intermarriage created ever more layers of complexity. Networks rarely served a single purpose, in much the same way that traders were not exclusively economic actors but also social and political beings. The analytical focus on networks can serve as an organizing principle for the multiple levels of material and intellectual connections across the ocean, without having to necessarily subsume them into claims of a coherent, overarching system.

Q. Your discussion of agents is multilayered and quite dense. I am curious to understand your model of partnerships as discussed in your work along with the role of slaves. How diverse are the roles of these agents in your analysis, both as an external and internal influencer, in the development of the networks?

The role of agents, both as commercial conduits and cultural ‘go-betweens’, has attracted a lot of scholarly attention in the past years. Work by scholars such as Natalie Rothman, Francesca Trivellato, Roxani Margariti, or Sebouh Aslanian have vastly expanded not just our empirical understanding of their functions, but also the conceptual tools for framing their personal and structural entanglements. My book seeks to add to that growing body of scholarship by highlighting the complexity and fluidity of many of those arrangements. And as you say, I’m particularly interested in the role of slaves as business agents, which is something I’ve worked on ever since my Masters thesis. Looking at the Malabar Coast, it is striking that several Arabic epigraphs state that a mosque was endowed or renovated by someone who in the inscription is explicitly identified as a former slave; in other cases, there are less direct but nonetheless quite compelling clues for this. As we know, for example from the Geniza records, slaves served as business agents in the maritime trade between Arabia and India. The extreme disparity in power between master and slave prompts the question of how principal-agent problems were resolved. But even when the agent was free and of equal status to the principal, their relationship required complex institutions in the context of the vast distances involved in oceanic trade, the slow and unreliable communication, and the ever-present temptations of malfeasance. It was only really through networks that these relationships could be managed and constrained. Premodern trade was an inherently social activity, and many of the social conventions and practices that we come across in the sources also, or even primarily, served an economic purpose.

Q. You discussed du‘ā al-sultān being carried out in the Friday prayers (khutba), in Malabar region, with the name of Rasulid sultans purely as a ritual through which Malabar rulers could develop close affinity with rulers of Aden and extract trade benefits. However, ritual aspect aside, what impact did this act have in challenging native authority over time?

In recent years, a number of new sources for the medieval Indian Ocean have become accessible to scholars. One of the most significant of these is a thirteenth-century chronicle from Yemen that contains a list of annual payments made by the Rasulid sultans to Muslim communities in coastal India. These stipends were not ceremonial investments like robes of honor; they were direct and regular payments to the religious leaders of merchant communities all along the Indian coast, to be conveyed annually with the merchant fleets from Aden. Éric Vallet was first to interpret this practice as an expression of a Rasulid “oceanic policy,” designed to boost Aden’s commerce and promote the dynasty’s self-appointed role as champions of Muslim communities across the Indian Ocean. Notably, the places detailed in the ledger—in Gujarat and the Konkan, on the Malabar and Coromandel coasts—were all under Hindu rule at the time. To extend patronage to judges and preachers who reside in the territory of another Muslim ruler would have been an unmistakable claim to political suzerainty that no self-respecting sultan would have tolerated. In lands under Hindu rule, however, the Rasulids could act as the benefactors and patrons of the local Muslim communities without calling into question the sovereignty of the local king.

This investment was repaid by at least some of those Muslim communities in a symbolic currency. It took the form, as you mention, of the du‘ā al-sultān or “invocation of the ruler”, which formed part of the Friday prayer (khutbah). Its purpose was to openly declare the relationship between a city or territory and its ruler. The dedication of this congregational prayer was a highly symbolic act: when a new sovereign was installed, the altered khutbah is frequently noted in the annals as the most significant public affirmation of the new political reality. As is known from different sources, Muslim communities in coastal India oftentimes invoked distant Muslim rulers in their khutbah. To a degree, Muslim traders on the Malabar Coast were able to pursue their own foreign policy, which of course was directed towards cordial relationships with important trading partners, perhaps in the hope of gaining tax exemptions. From a merchant’s point of view, dedicating the Friday sermon to the ruler of Aden was a richly symbolic, yet entirely free, way of substantiating vital economic ties.

For Muslim merchants living in the Hindu states of the Malabar Coast, invoking a foreign ruler in their khutbah was not in itself seen as a challenge to local sovereignty. That said, there were clearly also limits to this. For example, we don’t have any inscriptions about a Malabar mosque being endowed by, or dedicated to, a Muslim ruler. The building of mosques was an exclusively private endeavor, financed by merchants; anything else would likely have been viewed as a competing claim over land or people. So we don’t see the material and ritual ties that were forged across the ocean by Muslim rulers and Muslim merchants evolving into joint political projects on the Malabar Coast.

Q. One of the most fascinating chapters in your book deals with the syncretic nature of Islamic architecture in South and Southeast Asia. While your analysis supplements Richard Eaton and Phillip Wagoner’s work, I’m curious how it speaks to more recent works such as that of Chanchal Dadlani, i.e. does your study of the sources and architecture reflect any notion of the “ars memoria” tradition in the diasporic Islamic communities’ religious structures?

Beyond the textual inscriptions that they hold, my book tries to “read” the historic mosques of the Malabar Coast themselves as primary sources. In this, I build on the work of Eaton and Wagoner, whom you mention, but also scholars such as Stephen Dale, Alka Patel, and especially Mehrdad Shokoohy. Analogous to the idea of a “Monsoon Islam,”” the book argues for a discrete style of the “monsoon mosque” that we find in South India but also, in its own distinct iterations, in other Indian Ocean trading regions such as insular Southeast Asia or on the Swahili Coast. Again, this is not about the monsoon weather pattern as such, but rather about the interconnected trading world it encapsulated and about the dynamic between the global and local that I’ve mentioned before.

The monsoon mosque stands at this junction. On the one hand, it is a manifestation of a universalist faith that spanned across the ocean, as well as a key part of the commercial infrastructure that sustained those trans-oceanic linkages. On the other hand, its form is an expression of the syncretic processes by which Muslim communities became part of local societies and polities. The book looks at particular stylistic features, such as their multilayered tiled roofs, to explore the establishment, the meaning, but also the contestations of mosques within local landscapes of the sacred. In that sense, it touches on similar issues to those Dadlani so masterfully explores for the Mughals. In both cases, mosques serve as a cultural index, as a form of codified historical consciousness. For Muslim trade diasporas, mosques symbolized not just their presence but also a claim on a historical foundation in a place—and, of course, also an investment in their future there. It is this aspect of the book that I most look forward to expanding on once travel becomes possible again.

Q. You position your work as being inspired by the historiographical shift that sought to pluralize Islam through cultural interpretation that countered the orientalist perception of a “monolithic Islam,” while at the same time you discuss Arab ulema and Mappila ulema in your book. How do you negotiate the three-dimensional development of Islamic pluralism along with a hierarchical interpretation of Islam (i.e. native vs. foreign)?

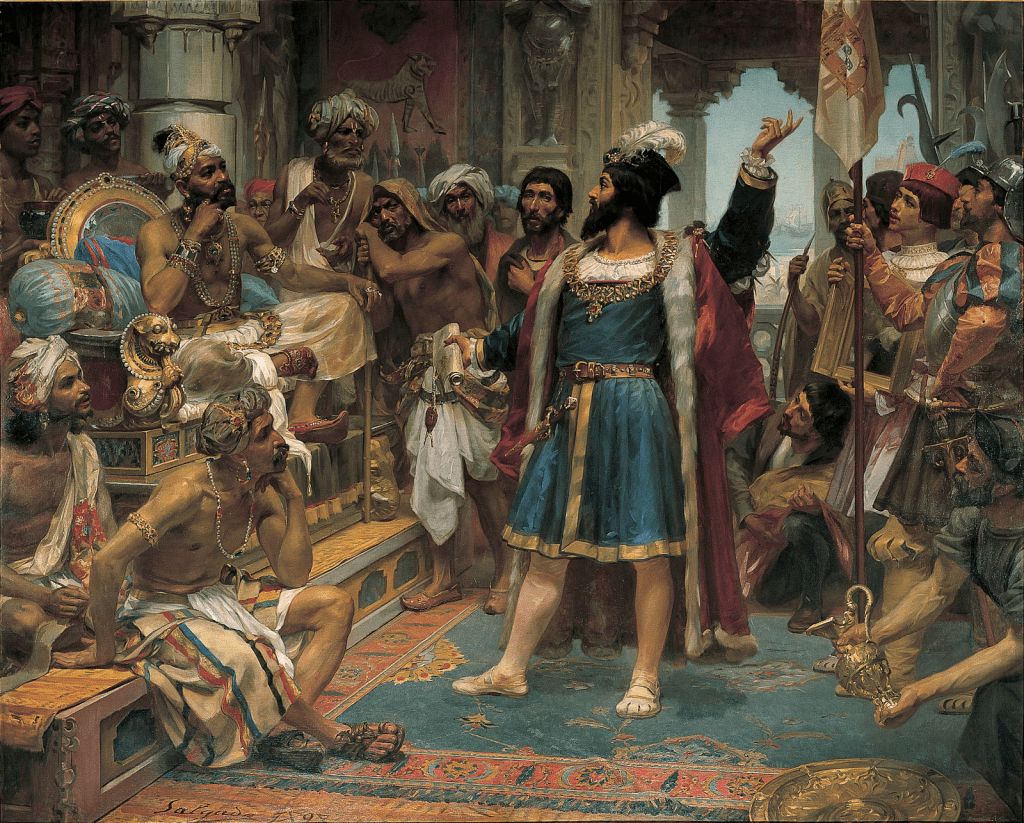

This is a really important question: clearly the binary between “foreign” and “local” Muslims is as problematic—-not to mention as false and as dangerous—-as that between a supposedly “authentic Islam” and a hybrid or syncretic faith. At the same time, we can’t simply elide the categories we encounter in the sources. Obviously, we find those crude dichotomies in European sources, for example in the Portuguese distinction between the “Moors of Mecca” and “Moors of the land.” But as my book shows, these identities were also very much at play within the Muslim merchant communities. Malabar’s ulama self-consciously promoted an Arabian ethnic identity to underpin their claims to status. This became one of the most prominent discursive projects that we can discern in the early sources. Then, in the sixteenth century, in the face of Portuguese aggression and the exodus of many Arab merchants, we see a refiguring of the ulama to project a more local, Mappila identity. We can even trace this shift within individual families, such as that of the famed Malabari scholar Zayn al-Dīn Makhdūm.

In Engseng Ho’s memorable image, Malabar’s Muslims were a community facing in two directions: on the one hand bound in complex relations with non-Muslim states and societies, and on the other engaged in intensive exchange with the wider trading world of the Indian Ocean and the Islamic cosmopolis. This duality means that it is misleading to speak simply of the ‘indigenization’ of a Muslim diaspora on the Malabar Coast. This is not to say that this process was not essential. It finds expression in such diverse phenomena as mosque architecture, changing compositions of the ulama, the development of new legal traditions, saint worship, and many other institutional and cultural facets. But it was taking place in conjunction with another dimension of interaction that linked them into networks of commercial partnership, economic institutions, religious learning, legal communitas, mysticism, political allegiance, and warfare. Monsoon Islam is the history of the interplay between these two dimensions in the economic, social, and political lives of Muslim merchant communities—it is the process of embedding global forces in local contexts, and vice versa. So, you’re absolutely right, we’re not looking at a binary or hierarchy, but rather at a multilayered and multidimensional exchange, which yielded distinct processes and outcomes for different communities, in different places, and of course also changed over time, with the sixteenth century as a particularly significant watershed.

Q. Your work’s objective, as highlighted by you, is to challenge the ‘static taxonomies’ that have dominated the study of history. In continuation of your objective, I am curious about the Eurocentric imagination of “piracy”. You briefly reflected upon the diverse perceptions of Mappila sailors as traders by local rulers but their simultaneous portrayal as “pirates” by Portuguese. Given your prior publications and the current monograph, how do you, epistemologically challenge the Eurocentric imagination of pirates in the Indian Ocean?

The brief mention of pirates in Monsoon Islam hints at a wider project I’m pursuing now, which examines the political dimensions of piracy in Asian waters. It challenges the conventional wisdom that Asian waters were great voids in indigenous political imagination and that Asian polities never regulated maritime space before the arrival of European empires. But as soon as we look at instances of maritime violence more closely, we quickly recognize its political dimensions, whether at the communal level or as part of rivalries and competing claims over trade routes and maritime spaces.

This realization forces us to reconsider the conceptual categories we have used to study and to develop new models for interpreting the role of piracy in Indian Ocean history. Situating Asian pirate communities within their local social and political settings highlights the severe shortcomings of projecting notions of legitimacy and sovereignty that are based on the European model of the modern nation-state back onto the premodern past. It shows that what European sources and historians have dismissed as mere piracy was, more often than not, the manifestation of the political contestation of trade routes and sea space by Asian potentates. The central aim of my project is not just to recover the voices and deeds of Asian seafarers, but to examine piracy as a historical category in the context of Indian Ocean history.

Accusations of piracy tend to accompany situations in which claims to sovereignty over maritime space are imposed, subverted, or openly contested. In this light, the study of piracy opens up questions about power relations, hegemonic practices, and permeable jurisdictions—questions that are at the heart of scholarly thinking about the emergence of the modern world order. In Asia as in Europe, the early-modern period was marked by a shift from fluid to more rigid parameters of social and political identity, from semi-private to public forms of warfare, and from personal to increasingly codified legal regimes. Recognizing that maritime violence was a crucial vector in all of these developments reveals the much-maligned pirate as a key player in the making of the early-modern world.

Q. You state in your acknowledgement that this work is the product of 10 years of labor, the foundation of which was laid during your doctoral studies at SOAS. Given this work is a product of your dissertation, could you highlight the alterations and changes the dissertation went through to reach the stage of a popular monograph?

Yes, it took me a very long time to turn the dissertation into a book. Other projects intervened, as did life in general, but the greatest challenge was to conceive of the empirical findings put forward by my doctoral research in terms of a broader argument. Inspired by my earlier studies at the LSE, my doctoral work was originally conceived as a quite narrow economic history of the pepper trade. But coming to terms with the ways that trade diasporas functioned forced me to grapple with social history—as I said earlier, premodern long-distance trade was inherently social. Partnership and agency agreements forced me to look at Islamic law, and in particular the interpretations of Shāfi‘ī law that were produced by Muslim merchant communities like those on the Malabar Coast. Before long, I was thinking not just about commodities and markets but about personal networks, scholarly affiliations, legal schools, and the nature of diaspora communities. The whole time, though, I was plagued (if that is a word we can still use) by the scarcity of sources. I had so many questions, and very limited means to address them. For that reason, the dissertation was really focused on establishing an empirical basis, while the writing of the book was much more about the interpretation.

All of which is to say, it was a really haphazard process, with no clear or predetermined end in sight. Now that I’m in the position of advising graduate students myself, I inevitably apply hindsight in trying to derive some kind of lesson from my experience that I can pass on. But what my experience exemplifies, above all, is the immense privilege I’ve enjoyed, which allowed me to pursue this quest, to trace the evidence and figure out the ideas that eventually coalesced into Monsoon Islam. It takes the resources of many institutions, the trust and support of numerous people, and countless other perquisites to research and write a book. This is what I want to acknowledge most about the entire process, from dissertation to monograph.

Q. Your work intersects multiple fields in terms of maritime history, Islamic pluralism, religious studies, economic history, political-military studies of littoral areas etc. What would be the 5 key works that either reshape the field of analysis or help us better understand the field when read together with your work?

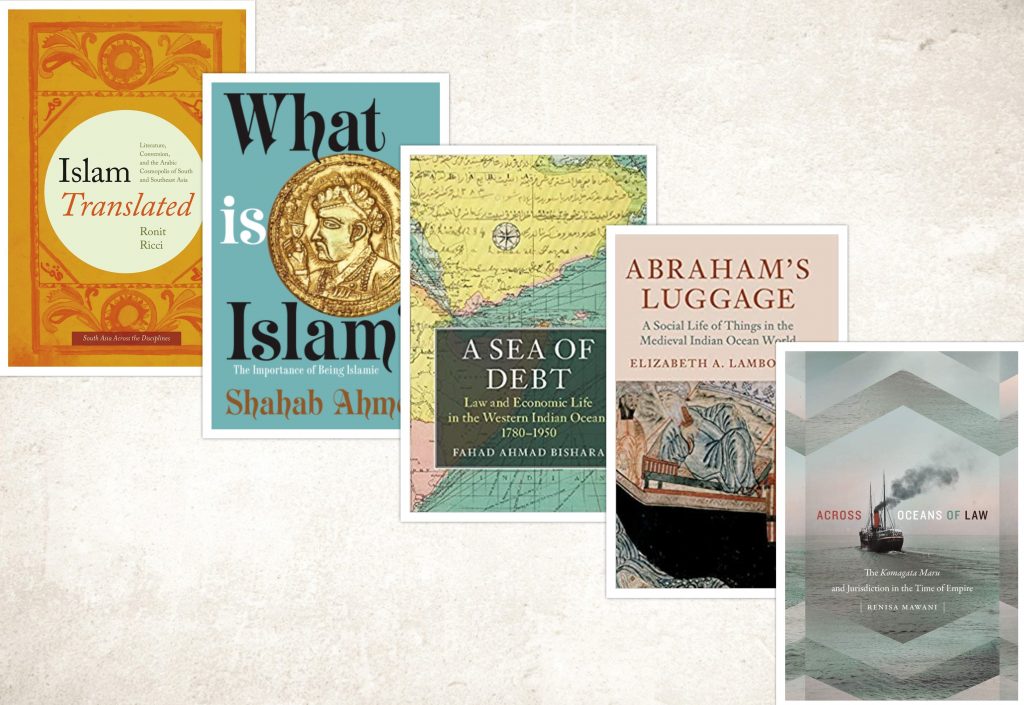

Here are five recent books I would feel very honored for Monsoon Islam to be read alongside with:

- Islam Translated by Ronit Ricci (2011)

- What is Islam? by Shahab Ahmed (2016)

- A Sea of Debt by Fahad Bishara (2017)

- Abraham’s Luggage by Elizabeth Lambourn (2018)

- Across Oceans of Law by Renisa Mawani (2018)

Anuj Kaushal is a PhD candidate in History at the University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses upon Islamicate healing practices and traditional medical science in South Asia. His work seeks to study identity formation and gender relations in South Asia through medical print culture, private consumption habits, and pluralistic approach to sexology during the 19th-20th century.

This is a revised version of an interview that appeared in https://www.chapatimystery.com/archives/xqs_xxii_-_a_conversation_with_sebastian_prange.html. With thanks to Chapati Mystery. Images reproduced with thanks from Sebastian Prange’s collection.

" data-envira-height="300" data-envira-width="264" />

" data-envira-height="300" data-envira-width="264" />