by Amina Marzouk Chouchene

First Published by The Imperial and Global Forum (August 28, 2019)

Twenty-first-century Britain brims with a revival of rosy visions of Britain’s imperial past. Nowhere is such a tendency clearer than in the restless efforts to rehabilitate the empire by prominent conservative historians such as Niall Ferguson. Britain’s imperial glories and its benign influence over the rest of the world are dominant themes in Ferguson’s popular writings such as his Empire: the Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power. According to him, the colonies hugely benefited from British colonialism’s gifts of free trade, free capital movements, and the abolition of slavery.

This celebratory examination of the British Empire has also become a part of the official political discourse at the highest levels of government. In his speech to the Conservative Party conference in 2011, David Cameroon looked back with Tory nostalgia to the lost days of empire. His speech evoked a mythologized version of Britain’s imperial past in which the empire was the ultimate force for good in the world. Theresa May also recently exalted the virtues of a “Global Britain,” “a great, global, trading nation that is respected around the world and strong.”[1] Most importantly, debates surrounding Brexit have highlighted how, for many Britons, the British Empire often reads as “a success story” about Britain’s “ruling the waves.”

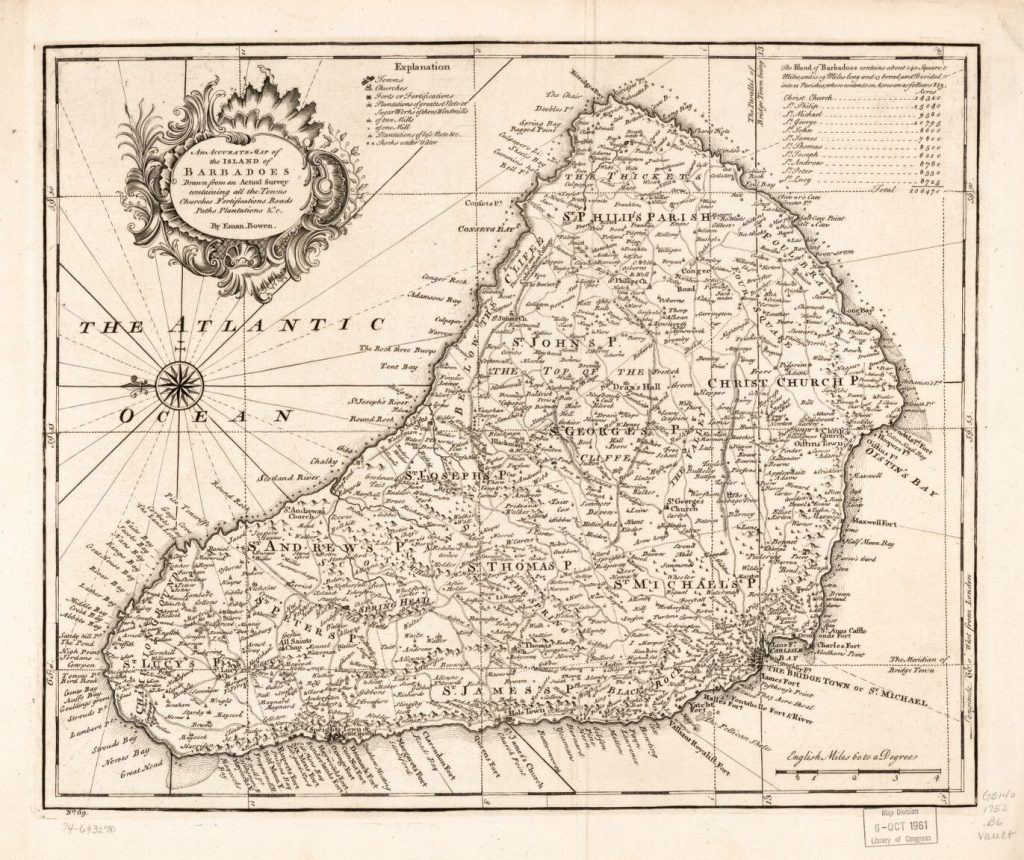

In contrast to this rosy vision of Britain’s imperial past, scholars are increasingly interested in tracing British imperial emotions: the feelings of fear, anxiety, and panic that gripped many Britons as they moved to foreign lands. Robert Peckham’s Empires of Panic: Epidemics and Colonial Anxieties (2015), Marc Condos’s The Insecurity State: Punjab and the Making of Colonial Power in British India (2018), the 2018 special issue in Itinerario on “The Private Lives of Empire: Emotion, Intimacy, and Colonial Rule,” and Kim Wagner’s Amritsar 1919: An Empire of Fear and the Making of a Massacre (2019) highlight the sense of vulnerability felt by the British in the colonies. Harald Fisher-Tiné’s edited volume Anxieties, Fear, and Panic in Colonial Settings is a welcome addition to this growing body of literature.

From the outset of the book, Fisher-Tiné highlights the pervasiveness of feelings of fear, anxiety, and panic in many colonial sites. He acknowledges that: “the history of colonial empires has been shaped to a considerable extent by negative emotions such as anxiety, fear and embarrassment, as well as by the regular occurrence of panics” (1). Bringing case studies from the British Empire as well as Dutch and German colonialism, the contributors uncover not only the pervasiveness of these emotions, but also their significant impact on colonial discursive and institutional strategies.

The volume consists of four main parts. The first discusses the effects of anxieties and panics over colonial minds and bodies. In this respect, David Arnold, for example, examines the poisoning panics in British India that were precipitated by Europeans’ fears of the supposed treachery of their Indian servants. Arnold affirms that poisoning panics have long been rife in India. Indeed, “under colonial rule, the country was subject to a long series of alarms and scares, some of which were sufficiently intense, and protracted to amount to ‘panics’” (49). Yet they were attributed to racial and political overtones in the nineteenth century. That is, the white elites were seen as particularly prone to this major threat. Arnold suggests that these excessive emotional states were triggered by three main causes. First, the European population in British India was heavily dependent on Indian servants and subordinates who might retaliate against unfair masters or whose access to European dwellings could be used by malevolent others to empoison the white elite. Second, anxieties about the assumed toxic effects of the Indian climate fuelled also poisoning panics. Diseases such as malaria and cholera were considered to be the ultimate outcome of an “atmospheric poison” (53). Third, Indian therapeutics and the system of medicine were also identified as a potential cause of poisoning European communities. These poisoning panics only helped reinforce the racial categorizations of Indians, the moral supremacy of the white population, and the legitimacy of colonial rule.

The second section of the collection deals with the “various kinds of discursive responses to imperial panics” (13). Focusing on the assassination of a high-ranking colonial official in London in the summer of 1909 by a Hindu student, for example, Fischer-Tiné pinpoints that the incident was used to demonize Indian anti-colonial activists such as Shyamji Krishnavarma. The latter “was one of the most important spokesmen of the Indian national movement in Europe in the early 1900s…and a sober nationalist with liberal leanings” (14). Nevertheless, following the London murder, he “was presented almost unanimously in official and semi-official and media accounts as the loathsome head of an international terror network” (101).

The third part examines the practical and institutional measures that were adopted to contain threats. These included the establishment of new systems of surveillance and discipline and even military intervention. On this subject, for instance, Daniel Brückenhaus considers British and French authorities’ fears of the potential alliances between anti-colonialists and Germans from 1904 to 1939. Interestingly, the author contends that “fears of German anti-colonial alliances motivated governments to extend their surveillance across inner-European borders” (226).

The final section explores “epistemic anxieties.” It focuses on how anxieties and panics led to the production, use, and circulation of colonial knowledge in imperial settings (17). In this regard, for instances, the chapter by Richard Holzl uncovers how missionaries’ panic over native sexual education in German East Africa led to the production of anthropological and religious knowledge in order to enable their fellow missionaries to deal with particular issues such as circumcision, and female genital mutilation.

Taken together, the thirteen contributors show the persistence of fears, anxieties, and panics in a wide variety of imperial settings and how colonial authorities sought to come to terms with this sense of vulnerability. The volume thus expands our understanding of how a sense of fragility rather than strength shaped colonial policies.

![]()

[1] Koo Koram, and Kerem Nisancioglu. “Britain: The Empire that never was.” Critical Legal Thinking, 31 Oct 2017, http://criticallegalthinking.com/2017/10/31/britain-empire-never/

![]()

You Might Also Like:

The Public Archive: Indian Revolt of 1857

Episode 48: Indian Ocean Trade and European Dominance

![]()