by Brian McNeil

Joseph Kony has been making waves across the Internet the past few days thanks to a slick, emotional video produced by Invisible Children, a nongovernmental organization based in San Diego, California. Who is Joseph Kony? He is the leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army, a brutal group from Uganda.  The LRA has devastated Central Africa, destroying towns, raping women, and, most infamously, kidnapping children and forcing them to fight. In 2005, the International Criminal Court put out a warrant for Kony’s arrest, and Kony and his cronies currently have the dubious honor of sitting near the top of the Interpol’s most wanted list. Despite being sought by the ICC and Interpol for over six years, Kony remains at large.

The LRA has devastated Central Africa, destroying towns, raping women, and, most infamously, kidnapping children and forcing them to fight. In 2005, the International Criminal Court put out a warrant for Kony’s arrest, and Kony and his cronies currently have the dubious honor of sitting near the top of the Interpol’s most wanted list. Despite being sought by the ICC and Interpol for over six years, Kony remains at large.

It took only a matter of minutes for Invisible Children’s video to go viral after the organization uploaded the film to YouTube on March 6. The thirty-minute video has been viewed over 76 million times, and the number is climbing. Social media sites have helped to further Invisible Children’s goals of making Joseph Kony “famous.” Almost everyone on Facebook has seen a link to the video. #Kony steadily climbed to 2.83 percent of all of the traffic on Twitter at midnight March 7 and has yet to dip below .09 percent. With over 200,000,000 tweets a day, that’s a lot of discussion on a subject that almost no one had heard about the day before.

The success of Invisible Children’s video has been matched by criticism of the organization. Critics have attacked everything from Invisible Children’s finances, motivations, and understanding of what is actually happening in Uganda. Many have brought back to life an older Foreign Affairs article that claims that organizations such as Invisible Children “have manipulated facts for strategic purposes, exaggerating the scale of LRA abductions and murders and emphasizing the LRA’s use of innocent children as soldiers, and portraying Kony . . . as uniquely awful, a Kurtz-like embodiment of evil.” Slate is linking to an Al Jazeera article that claims the story told in the video about Kony is outdated, that his power has now dwindled and he no longer operates inside Uganda. And today Nicholas Kristof takes on the critics in The New York Times.

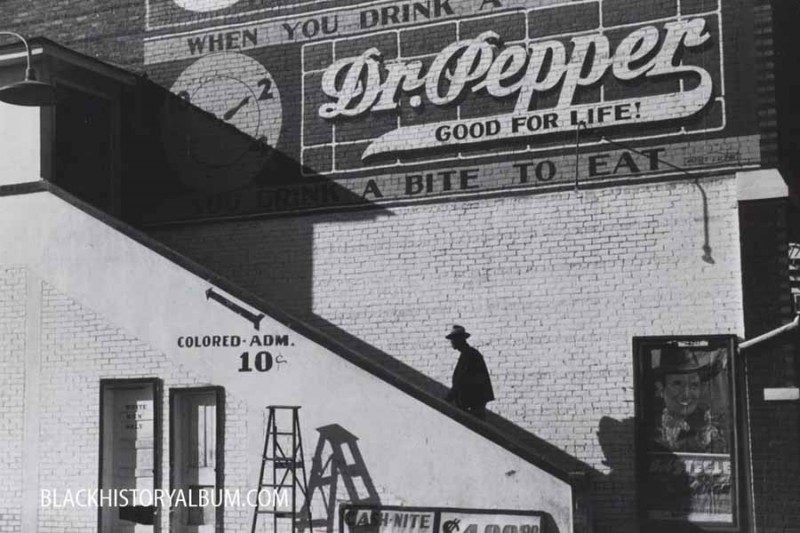

Constructing a good vs. evil paradigm to further a cause is, of course, nothing new. Invisible Children’s activism fits within a larger historical phenomenon of activists calling on governments to help downtrodden people on the basis of morality. The fight to end the African slave trade was one of the earliest and most successful examples. The patchwork quilt of twentieth-century activism is sewn together with a farrago of international disasters that paved the way for Invisible Children’s presentation of its subject. During the First World War, Brahmins assembled in Boston at Faneuil Hall to protest the Turkish government’s treatment of the Armenians. “Turkey might govern as she pleased,” one Bostonian appealed to his concerned friends, “but she was not permitted to outrage the sense of humanity.” During the 1980s, the same appeals to humanitarian morality rung like a church bell on our television sets with the fly-covered children of famine-wrecked Ethiopia; in the 1990s with the mass graves in Srebrenica; and in the late 2000s, with the gut wrenching pictures of what Colin Powell called “genocide” in Darfur.

Perhaps the most important piece of the quilt that set the stage for Invisible Children was activism during the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970). The images of emaciated women and children coming out of the secessionist state of Biafra stirred people across the United States toward activism. Over 200 nongovernmental organizations sprouted in the United States alone, all calling for the United States to help with the relief effort in Biafra. The American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive, the largest and most influential group, took out ads in The New York Times asking American President Richard Nixon if Nigerian unity was worth the lives of ten million people. In the New York Post, the organization compared the Nigerian head of state Yakubu Gowon to Hitler. Much like Invisible Children, the American Committee sought out and got celebrity endorsements, as Jimi Hendrix, Joan Baez, Cliff Robertson, Michael Caine, and countless others spoke out over Biafra. They all agreed with Ted Kennedy, then a junior Senator, that “the essence of international law is humanitarianism,” and the United States should support humanitarian relief.

But this is where the similarities between these previous organizations and Invisible Children largely end. While all these previous groups wanted the United States to become involved in helping peoples of other nations, they believed that aid should be handled under the flag of the United Nations or other supranational or regional groups. Invisible Children has advocated for the United States to send its troops unilaterally into Central Africa under its own flag. This is an extraordinary demand given that the United States has just left a nasty intervention in Iraq and is currently struggling to extricate itself from Afghanistan. The historical trend had been for the American public to shy away from more use of the U.S. military after intervening in Vietnam, Somalia, and Iraq.

By suggesting that the United States military not only could, but should, send its own troops under its own mandate to help capture Joseph Kony and “save” Ugandan children, Invisible Children has inserted itself into a centuries old debate on America’s role in the world. John Quincy Adams warned in 1821 that while evil existed in the world, the United States should act alone and not go abroad “in search of monsters to destroy.” A century later, Woodrow Wilson argued that it was in the interest of the United States to seek out those monsters, but it should only be done in concert with a League of Nations. Invisible Children’s call for action, then, seems to be an interesting mix of the two: acting unilaterally with American military power to destroy monsters like Joseph Kony.

The blending of unilateral American force and moral concern should sound familiar because it was precisely the logic of the George W. Bush administration and its neoconservative foreign policy. The most striking aspect of the Invisible Children’s campaign is that the use of American troops to enforce moral imperatives has been almost unquestioned by its supporters. And judging by the money that is pouring in, the support for this foreign policy seems massive. Maybe to this younger—and judging from the video mostly white—generation, sending American troops on moral missions is not problematic and in fact should be the guide to America’s foreign policy in the future.

Are we witnessing a resurgence of neoconservative foreign policy? Probably not. Instead, we are seeing the ability of humanitarian morality to transcend politics and ideology and forge bonds amongst people across the globe. The Internet has amplified this process, not only making it easier and faster to share information about important issues, but fostering a sense of democratic connection that makes us feel as if Joseph Kony is our problem, too. Invisible Children has been successful for the same reasons that the abolitionists succeeded in persuading Parliament to end the slave trade: they portrayed their subjects as a human tragedy that rose above politics.

The danger, of course, is that by constructing the Ugandan situation as a fight between good and evil, Invisible Children’s advocates are supporting a military initiative that they might normally dissent against. It is not that Invisible Children’s supporters do not understand the alleged lessons of intervention in Afghanistan and Iraq. Rather, Afghanistan and Iraq are not seen as applicable to a moral situation like the eradication of Joseph Kony. This sounds eerily similar to the well-meaning American intervention in Somalia during the early 1990s. Let’s hope that this American intervention works out better than the last time the United States tried to destroy a monster in Africa or the Middle East.

You may also enjoy:

David Rieff, A Bed for the Night: Humanitarianism in Crisis (2003)

Photo Credits:

Interpol

Swarthmore College Peace Collection

Public servants, like mail carriers and police officers were especially vulnerable to the disease and helped spread it. The suffering the flu wrought on the Indian population is well documented because the federal government was supposed to administer reservations.

Public servants, like mail carriers and police officers were especially vulnerable to the disease and helped spread it. The suffering the flu wrought on the Indian population is well documented because the federal government was supposed to administer reservations.