Prof Juliet E. K. Walker recalls being a student of the great pioneer of African Amercian history and discusses his importance to history writing and teaching.

[jwplayer mediaid=”5997″]

And take a look at a video lecture by John Hope Franklin in the collection of the Briscoe Center for American History at The University of Texas at Austin

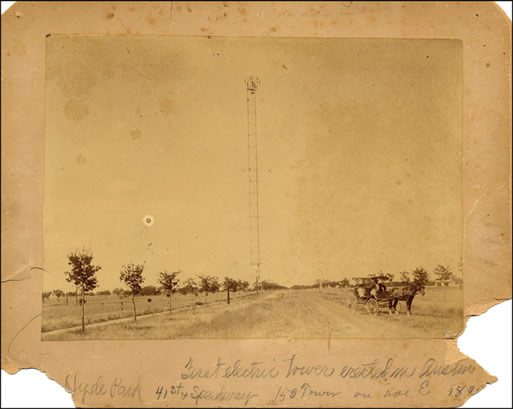

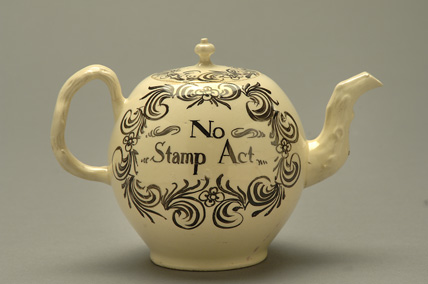

A few years ago, after discussing the origins and consequences of the

A few years ago, after discussing the origins and consequences of the

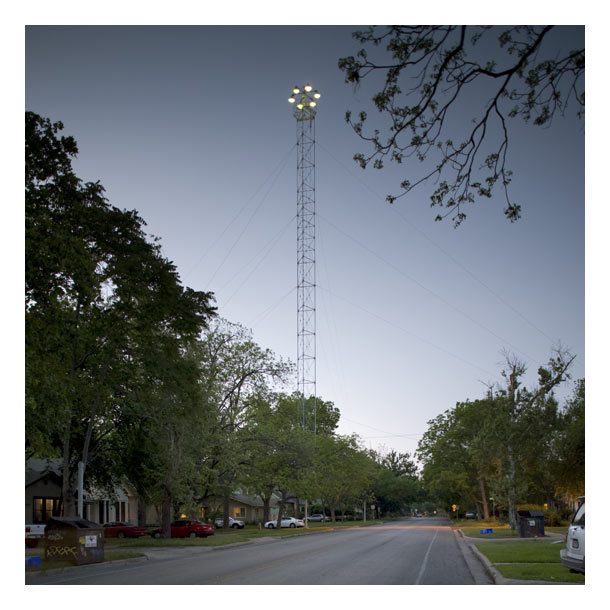

By George Christian

By George Christian

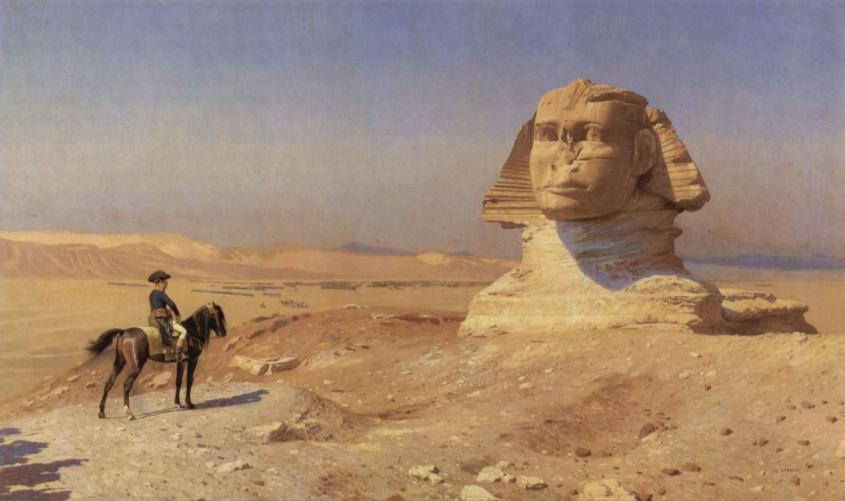

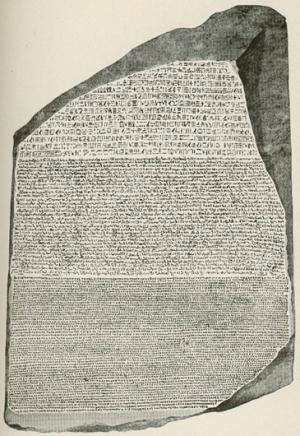

Antiquarianism during the Renaissance and Enlightenment again made Egypt an object of desire. When Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798, he brought along a bumptious team of French savants who

Antiquarianism during the Renaissance and Enlightenment again made Egypt an object of desire. When Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798, he brought along a bumptious team of French savants who

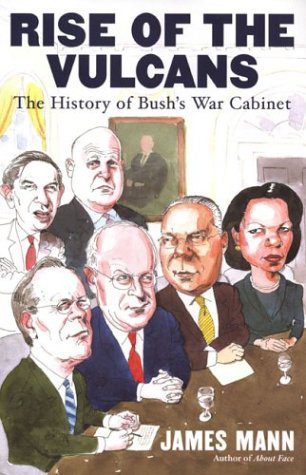

Lockman’s concern is that certain kinds of knowledge about the Middle East and Islam have been used to shape and justify dangerous policies without the consent of an informed public.

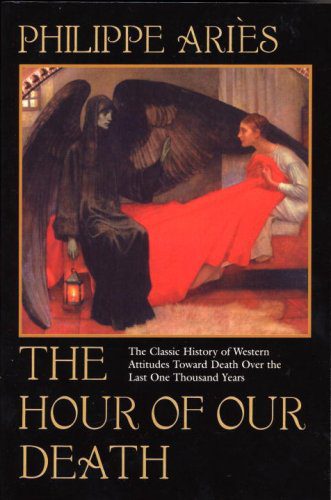

Lockman’s concern is that certain kinds of knowledge about the Middle East and Islam have been used to shape and justify dangerous policies without the consent of an informed public. Philippe Ariès’ monumental work, The Hour of Our Death, was something of an exception, as it offers rare insight into European representations of death from the eleventh century to the twentieth. Beautifully written and admirably translated, the work takes the reader through a dizzying array of cemeteries, epic poems, and deathbeds to provide a view of the ever-evolving place of death in European society. After reading it, one will never look at death the same way again.

Philippe Ariès’ monumental work, The Hour of Our Death, was something of an exception, as it offers rare insight into European representations of death from the eleventh century to the twentieth. Beautifully written and admirably translated, the work takes the reader through a dizzying array of cemeteries, epic poems, and deathbeds to provide a view of the ever-evolving place of death in European society. After reading it, one will never look at death the same way again.