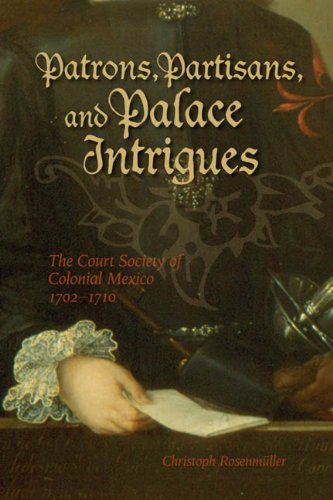

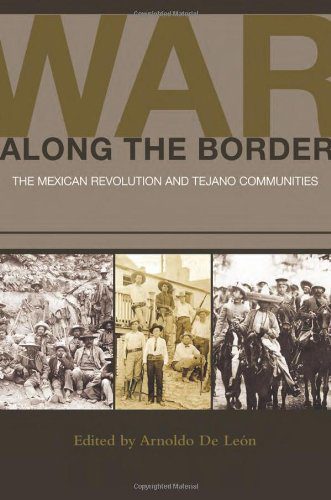

The “war on drugs” originated in the late nineteenth century when the United States and Mexico began to combat the narcotics industry. By 1914, the Harrison Act criminalized non-medicinal use of opiates and cocaine in the United States. Likewise, with the ratification of the 1917 Constitution, Mexico tried to terminate the distribution of drugs with strict bans on the production and importation of opiates, cocaine, and marijuana. Before 1920, both countries had declared war on drugs. In A Narco History, Boullosa and Wallace explain how the battle against drugs has enriched narcos, escalated violence, and increased the demand for illegal substances.

The “war on drugs” originated in the late nineteenth century when the United States and Mexico began to combat the narcotics industry. By 1914, the Harrison Act criminalized non-medicinal use of opiates and cocaine in the United States. Likewise, with the ratification of the 1917 Constitution, Mexico tried to terminate the distribution of drugs with strict bans on the production and importation of opiates, cocaine, and marijuana. Before 1920, both countries had declared war on drugs. In A Narco History, Boullosa and Wallace explain how the battle against drugs has enriched narcos, escalated violence, and increased the demand for illegal substances.

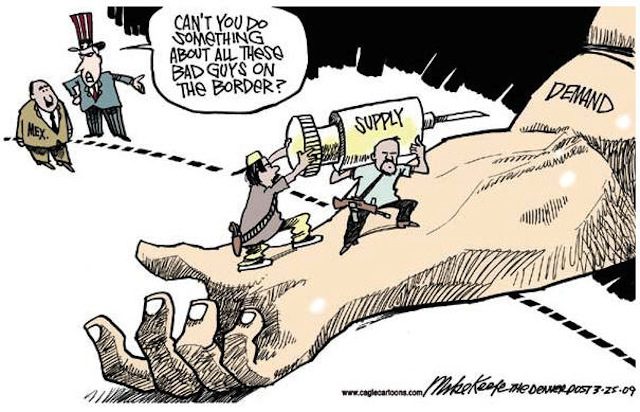

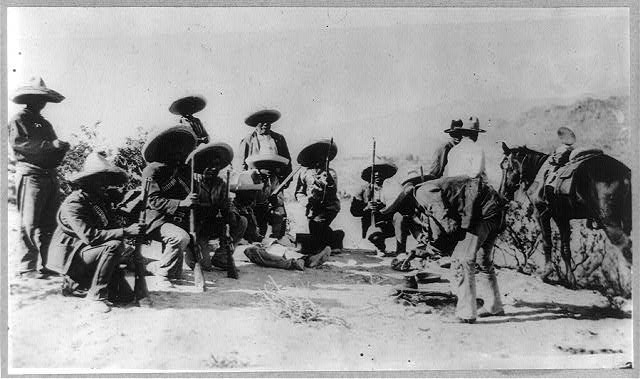

Boullosa and Wallace begin by recounting the events of 2014 that led to the horrific murder of 43 students from Ayotzinapa in the state of Guerrero. Although the truth about this case remains obscure today, the authors suggest foul play rooted in collaboration between the federal government, local politicians, and drug-related gangs. The remainder of the book details the convergence of federal and local politicians with drug dealers since the late nineteenth century. Spanning from Mexico’s Porfiriato to Obama’s administration, the twelve chapters explore how the actions of one government, typically those of the United States, resulted in the expansion of the drug trade. For instance, Boullosa and Wallace argue that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which favored U.S. agribusiness, forced thousands of Mexican farmers to turn to marijuana and cocaine production. This deepened the local dependence on the drug market and provided a greater supply for the insatiable demand in the US. Similar instances of cause and effect, which typically benefited the United States to the detriment of Mexicans, occurred throughout the century.

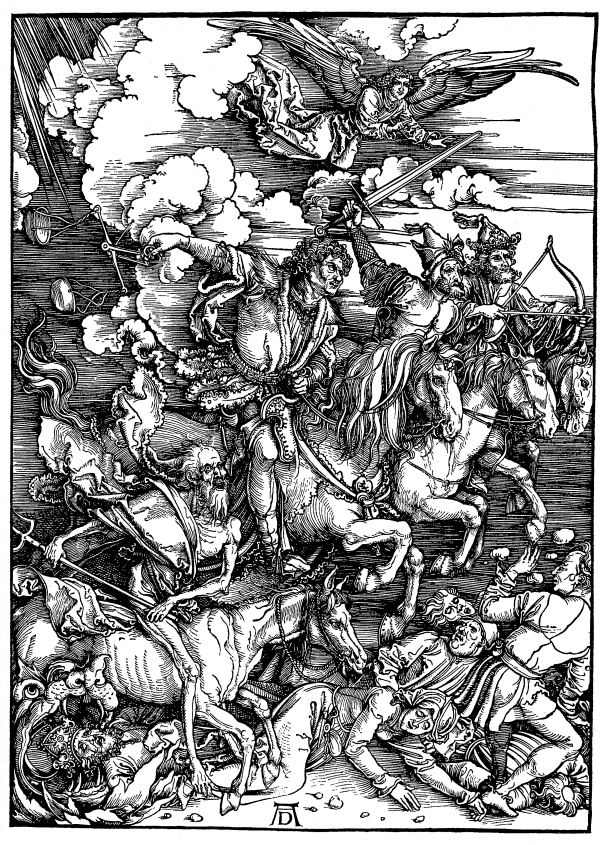

Cempasuchil petals form human-shaped outlines on the ground beside lit candles and a placard during an event held in remembrances of the 43 missing student teachers from the Ayotzinapa. Via REUTERS/Henry Romero

A Nacro History will get any interested reader up-to-speed on the history of this oft discussed “war on drugs.” Beyond a simple timeline, Wallace and Boullosa spell out the implications of political corruption, neoliberalism, the arms trade, and American exceptionalism. U.S. drug policies and pressures on Mexico to squelch the trade ensured the proliferation of “cartels” and the movement of narcotics. The elimination of one “drug lord” inevitably led to the fissuring of cartels and the increase in “collateral criminality,” like kidnapping, rape, extortion, and murder. The authors end the history with a few suggestions for both countries on how to ameliorate the situations for the victims of the drug war violence. Considering the attention given to US-Mexico border issues in the upcoming presidential elections, readers will find their propositions useful.

The clear writing style and the absence of intimidating footnotes makes A Narco History extremely accessible (even if it might raise questions for academic readers seeking its sources). The lively vignettes on individuals ranging from corrupt politicians and extravagant narcotraficantea to opportunistic agriculturalists and heroic victims, will prove especially interesting to undergraduates and nonacademic audiences. A Narco History will leave many readers eager to embark on research of their own, which they can begin with the book’s excellent bibliography.

You may also like:

NEP’s collection of articles on US-Mexico Interactions

The perpetrator, a Spaniard named Ramón Mercader, confessed to the murder, but initially refused to discuss his motives (he was only later confirmed to be a Stalinist agent). To dissect the tight-lipped Mercader’s mindframe, criminologist Raúl Carrancá y Trujillo drew out his own ice-axe:

The perpetrator, a Spaniard named Ramón Mercader, confessed to the murder, but initially refused to discuss his motives (he was only later confirmed to be a Stalinist agent). To dissect the tight-lipped Mercader’s mindframe, criminologist Raúl Carrancá y Trujillo drew out his own ice-axe: