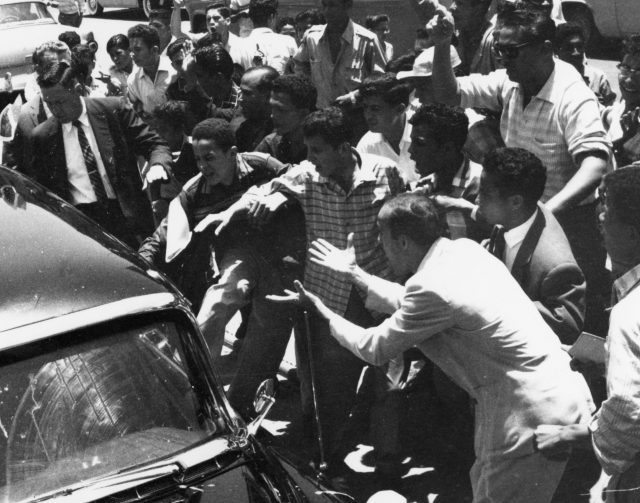

This week, Jeremi and Zachary have a discussion with Dr. Emily Whalen about Lebanon’s complex history and its current conflict.

Zachary sets the scene with his poem, “A Prophecy”.

Dr. Emily Whalen is a non-resident senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Her first book, The Lebanese Wars, which examines the history of U.S. interventions in the Lebanese Civil War, is forthcoming from Columbia University Press in 2025. She earned her PhD in 2020 from the University of Texas at Austin.