Since we are launching our blog as August crawls towards September and our thoughts are turning to the classroom, it is fitting to begin with an essay about what historians do during the summer.

Summer, Interrupted by Rachel Herrmann

“Summer vacation” is a misnomer for what we academics do from mid-May to late-August. Most of us are not on vacation, but many of us are definitely a little unreachable. Professors become difficult to chase down. Not Even Past goes a bit off the grid. Grad students might go to the pool, or to coffee shops that play slightly more rousing music, but they do so with a book in hand. During this period, we all become somewhat selfish with what we see as our few uninterrupted months of reading, research, and writing time. Other academics have written about this phenomenon: Gabriela Montell over at The Chronicle of Higher Education has dubbed it “The Fantasy of the Faculty Vacation,” and Mark R. Cheathem, Associate Professor of history at Cumberland University, has blogged about what makes summer funding essential for research and writing support. This year has been my first year of dissertation research, and I have spent it traveling around the country to various archives and libraries. My summer, consequently, was not significantly different from the rest of my year.

The fact that other people were suddenly on summer break, however, meant that I traveled more widely, and engaged in a few other activities besides research. If the fifth grader inside of me had to describe my summer vacation, she would say, “It was super cool.” She might also say, “It was totally awesome!” but that’s probably because she doesn’t know how to drive, and thinks that it will be exciting to travel halfway across the country from Austin to Los Angeles. Oh, the things my fifth-grade self doesn’t know; she hasn’t seen what West Texas looks like after six straight hours of scraggly brown bushes. But more on that later.

The fact that other people were suddenly on summer break, however, meant that I traveled more widely, and engaged in a few other activities besides research. If the fifth grader inside of me had to describe my summer vacation, she would say, “It was super cool.” She might also say, “It was totally awesome!” but that’s probably because she doesn’t know how to drive, and thinks that it will be exciting to travel halfway across the country from Austin to Los Angeles. Oh, the things my fifth-grade self doesn’t know; she hasn’t seen what West Texas looks like after six straight hours of scraggly brown bushes. But more on that later.

This is the point where I should stop and admit that I did, in fact, go on a vacation—a brief one—at the beginning of May. I have a younger sister who is majoring in International Relations, and who had just spent a semester at Cape Town University, in South Africa. Before that she was in Cairo, and before that, Morocco. Except for a brief visit over Christmas, I’d not seen her for a year. My mother—after reminding me that life is not all about research, guilting me about not seeing my family enough, and whispering tempting words like “safari” and “leopards” into my ear—lured me to Zimbabwe, Botswana, and South Africa for a family vacation.

Cheetahs, elephants, leopards, lions, water buffalo, zebras, and antelopes of various sizes notwithstanding, I wasn’t really in powered-off scholar mode, not even on standby.  On our sixteen-hour flight to Johannesburg, I read a book I was supposed to be reviewing, and started making notes on a yellow legal pad. I began writing a sentence or five after meals of crocodile and kudu (a type of antelope), and soon felt like I had a good enough grasp of the book to begin stringing paragraphs together. I put the finishing touches on the review a week and a half later while sitting in a camp bed that was placed on a raised wooden platform that was covered with canvas tent walls—and that was, at the time, being bounced on by a troupe of baboons. We got up at 5 a.m. for safari game drives, and in the long stretches of Botswanan bush not occupied by lazing lions, I crafted dissertation sentences in my head. I planned my research schedule for the next four months. I lay awake at night and worried about pending grant applications.

On our sixteen-hour flight to Johannesburg, I read a book I was supposed to be reviewing, and started making notes on a yellow legal pad. I began writing a sentence or five after meals of crocodile and kudu (a type of antelope), and soon felt like I had a good enough grasp of the book to begin stringing paragraphs together. I put the finishing touches on the review a week and a half later while sitting in a camp bed that was placed on a raised wooden platform that was covered with canvas tent walls—and that was, at the time, being bounced on by a troupe of baboons. We got up at 5 a.m. for safari game drives, and in the long stretches of Botswanan bush not occupied by lazing lions, I crafted dissertation sentences in my head. I planned my research schedule for the next four months. I lay awake at night and worried about pending grant applications.

At the end of the trip, my family was probably glad to see me go so that they didn’t have to gaze into my panic-stricken face any longer. My mother boarded a plane home to New York, and I got onto a plane bound for London: or, more particularly, the British Library and the National Archives. I landed on a Sunday and lamented the fact that all the archives were closed, and that it was too early to check into my hostel. I made the best of things by walking to Buckingham Palace to see the changing of the guard, and ate a sandwich in a state of jetlagged stupor while listening to people ranting at Speaker’s Corner over the benefits of atheism. Finally, I collapsed at the hostel for a long-awaited nap, and woke up a few hours later to the new arrivals in my room. The upside to staying in a hostel is the amount of money you save. The downsides involve noisy, rude roommates, and never knowing who will end up in the bunk bed on top of yours for the coming week. I prefer light, noisy sleepers to smelly feet, but that’s just my personal preference.

I made the best of things by walking to Buckingham Palace to see the changing of the guard, and ate a sandwich in a state of jetlagged stupor while listening to people ranting at Speaker’s Corner over the benefits of atheism. Finally, I collapsed at the hostel for a long-awaited nap, and woke up a few hours later to the new arrivals in my room. The upside to staying in a hostel is the amount of money you save. The downsides involve noisy, rude roommates, and never knowing who will end up in the bunk bed on top of yours for the coming week. I prefer light, noisy sleepers to smelly feet, but that’s just my personal preference.

The next morning I ate the universal hostel breakfast of strong tea and a bowl of cereal, while reflecting on my budding caffeine headache and wondering how soon it would take to kick my coffee addiction. Thankfully, at least, this hostel did not subscribe to the apparently general British idea that whole milk is the only thing that belongs on cereal. After breakfast, I made the short walk to the British Library, and breathed a sigh of relief. Not only was I back in the research saddle, but I’d been to this library before and knew how the system worked.

What follows is my prescriptive advice for staying sane on a research trip (or trips).

When you are in London for research, you should bounce back and forth between the British Library and the National Archives. Sundays are the only days when both archives are closed, and on these days you should sleep later, and then see as much of London on foot as you can. Go to the Churchill War Rooms so that you can talk about them at UT’s British Studies; browse the stalls at Covent Garden for cheap gifts for friends. You should time your moment of exhaustion with your arrival in Chinatown, where you should drink copious amounts of green tea and eat an embarrassing amount of Dim Sum. Obviously, if you’re lucky enough to be sharing London with current and former UT grad students, you should meet them for Indian food, Italian fare, and drinks as frequently as possible. I recommend skipping the Mexican restaurants, however, as they will only disappoint you.

Once you’ve squeezed every primary source you can from the archives (or the money runs out), get back on a plane and fly to New York City. Borrow your mother’s car to drive to SUNY New Paltz for a conference. Attend as many panels as you can on the first day, but slink back to your dorm room on the second day to give in to your jet lag with a three hour nap. Then, get Chinese food from a strip mall and eat it in your room because sometimes, you just don’t have the energy to network with anyone else. Rally for the third day of panels, hand out business cards at the reception, ask postdocs about how they got their fellowships and jobs, and have two sentences at the ready to describe your dissertation to anyone who asks. Drive back to New York City, pack your suitcases for what feels like the twentieth time in a year, get on a plane, and enjoy the feeling of being wheels-down in good old Austin, Texas.

Once you’ve squeezed every primary source you can from the archives (or the money runs out), get back on a plane and fly to New York City. Borrow your mother’s car to drive to SUNY New Paltz for a conference. Attend as many panels as you can on the first day, but slink back to your dorm room on the second day to give in to your jet lag with a three hour nap. Then, get Chinese food from a strip mall and eat it in your room because sometimes, you just don’t have the energy to network with anyone else. Rally for the third day of panels, hand out business cards at the reception, ask postdocs about how they got their fellowships and jobs, and have two sentences at the ready to describe your dissertation to anyone who asks. Drive back to New York City, pack your suitcases for what feels like the twentieth time in a year, get on a plane, and enjoy the feeling of being wheels-down in good old Austin, Texas.

Stuff your face with Italian specials at Vespaio, Tex-Mex at Trudy’s, Thai food at Titaya’s, and sushi at Maru. Plan your life while consuming half-off coffee before 11 a.m. at Dolce Vita. See friends for happy hour and spontaneous barbecues. Pack your bags, again.

Take a deep breath, and get into your car. Drive to Arizona. Stop and sleep. Finish the drive to California. Begin your month of research in San Marino with a daily commute with some of the fastest (and worst) drivers in the country. Cling to David Sedaris on CD as the only thing that will keep you sane as you sit bumper-to-bumper on I-10 and the 101. Give a talk to a group of 40 donors during your first week at the archives, on a topic you haven’t spoken on yet, so that you are forced to fine-tune two dissertation chapters. Attend another conference in Philadelphia and get back to California while the 405 is still ostensibly closed and L.A. is supposed to be mired in Carmageddon. Breathe a sigh of relief when Carmageddon fails to occur. Hyperventilate upon realizing that your commute still exists. Write another book review. Locate UT graduate students in California who want to meet you for happy hour, and high school and college friends who are willing to indulge your growing obsession with Dim Sum.

Finish your research in California, and start the drive back to Austin. Smile fondly at the red rocks of New Mexico, border checks in Arizona, and windmills dotting the dry landscape of West Texas, because you’re going home, home, home sweet home. Caution: resist the temptation to speed on TX-71; it never ends well because there are too many traffic lights.

Settle back into the Texas heat by jogging before noon, after which the sun makes exercise an unreasonable struggle. Pick up books from the Perry-Castañeda Library. Run into another grad student at Titaya’s who’s a week away from his dissertation defense, and take comfort in the fact that he looks calm. Vigorously scrub the bathroom in the apartment so that you are exhausted enough not to repeat the night where you decided that sleep was a fruitless endeavor and your dissertation needed a new introduction at 1 a.m. Buy Anthony Bourdain’s books on the cheap at Half Price Books, and use his food writing to inspire you. Schedule ten million meetings with professors as they begin to reappear on campus. Get your oil changed. Visit your storage unit, and obtain a slew of clothes for winter in Philadelphia. Resist the urge to “rescue” every single pair of shoes you own from storage. Pack.

Summer vacation, indeed. My inner fifth grader can’t wait for the start of the school year.

Photo Credits:

All Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Woman Sitting on a Beached Boat, Reading a Book, c. 1925, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

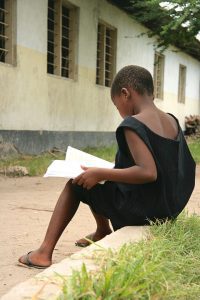

Child in Tanzania reading a book, Frank Douwes

Old section of Natchez, Mississippi. Woman sitting on park bench reading, Infrogmation of New Orleans

Portrait of a woman, reading a book in a lounge chair in the garden, F.W.M. Kerchman, Tropenmuseum

Reading Woman in the Forest, Gyula Benczúr

A muslim woman reading the koran in the mosque on the first day of Ramadan, by

Dhr. J.D. (Jacob Derk) de Jonge,Tropenmuseum

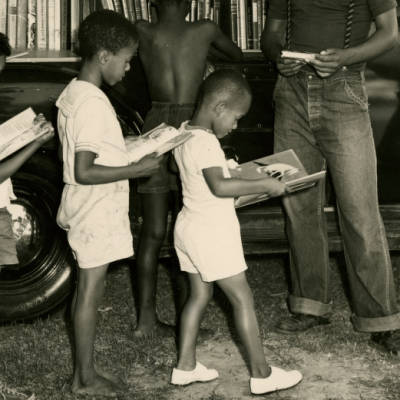

African-American children line up outside of Albemarle Region bookmobile, State Library of North Carolina

A Real Page Turner… By dregsplod from Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA, Creative Commons

Woman Reading, Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Two women reading on a verandah at Ingham, ca. 1894-1903, Harriett Pettifore Brims, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Schwarz’s life may well have been forgotten if he had not taken the unusual step of memorializing it in an extraordinary manuscript. In his Klaidungsbüchlein, or “Book of Clothes,” Schwarz commissioned one hundred and thirty seven vivid watercolor paintings depicting the clothes he wore at each stage of his life, from his “first dress in the world” as a days-old infant to the somber robes of mourning he wore as a world-weary man of sixty-seven.

Schwarz’s life may well have been forgotten if he had not taken the unusual step of memorializing it in an extraordinary manuscript. In his Klaidungsbüchlein, or “Book of Clothes,” Schwarz commissioned one hundred and thirty seven vivid watercolor paintings depicting the clothes he wore at each stage of his life, from his “first dress in the world” as a days-old infant to the somber robes of mourning he wore as a world-weary man of sixty-seven.

If the UN displayed the city’s position as a global capital of culture, politics, and economics, the deteriorating housing projects showed the city’s struggles with overcrowding, high crime rates, and poverty. According to historian

If the UN displayed the city’s position as a global capital of culture, politics, and economics, the deteriorating housing projects showed the city’s struggles with overcrowding, high crime rates, and poverty. According to historian  The transition from decades of Belgian colonial brutality and paternalism to independence, as historical records reveal, did not go smoothly. Gender and Decolonization in the Congo departs markedly from most work on this process by focusing on gender. There is a tendency on the part of scholars to neglect gender in their histories of decolonization in Africa. Political scientists, for instance, are apt to focus on the rise of the Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union. Much historical scholarship on the DRC shows enthusiasm for resolving puzzles arising from the perennial question: who assassinated Patrice Lumumba?

The transition from decades of Belgian colonial brutality and paternalism to independence, as historical records reveal, did not go smoothly. Gender and Decolonization in the Congo departs markedly from most work on this process by focusing on gender. There is a tendency on the part of scholars to neglect gender in their histories of decolonization in Africa. Political scientists, for instance, are apt to focus on the rise of the Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union. Much historical scholarship on the DRC shows enthusiasm for resolving puzzles arising from the perennial question: who assassinated Patrice Lumumba?

Inside the front cover of the textbook a message from the Alabama State Board of Education stated: “This textbook discusses evolution, a controversial theory some scientists present as a scientific explanation for the origin of living things, such as plants, animals, and humans.”

Inside the front cover of the textbook a message from the Alabama State Board of Education stated: “This textbook discusses evolution, a controversial theory some scientists present as a scientific explanation for the origin of living things, such as plants, animals, and humans.”

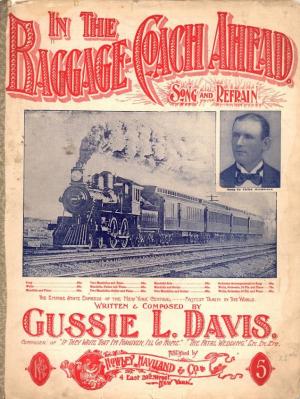

The song was the most popular composition of

The song was the most popular composition of  In 1925, he re-imagined himself as a hillbilly singer and achieved his greatest popularity with

In 1925, he re-imagined himself as a hillbilly singer and achieved his greatest popularity with