By Jimena Perry

In 2013, a memory museum opened in Medellín, Department of Antioquia Colombia. Its founding was part of the Victim Assistance Program created by the city’s mayoralty in 2004. Known as one of Colombia’s most violent cities, due mainly to the drug cartel of Medellín led by Pablo Escobar, this urban area suffered severe violence (bombings, targeted killings, kidnappings, bribes, threats, and massacres) from the 1980s to the mid-1990s. The communes of Medellín ‒16 divided into neighborhoods and institutional areas‒ acquired a very bad reputation during this period because most forms of violence happened there. According to official sources, such as the National Registry of Victims, 1,383.988 of 8,421,627 registered victims nationwide, are from the Department of Antioquia.

The house-museum (casa museo) is conceived as part of the symbolic reparation of victims the state must pursue, as a space in which they can grieve, come together to tell their stories, and heal. The museum has 378 testimonies that can be heard, viewed, and read. The building in which it is housed has three stories. The first one is a temporary exhibition space, the second is where the permanent display is, and the third is a documentation center. Located downtown, the museum is at the Bicentenario Park and behind a traditional theatre.

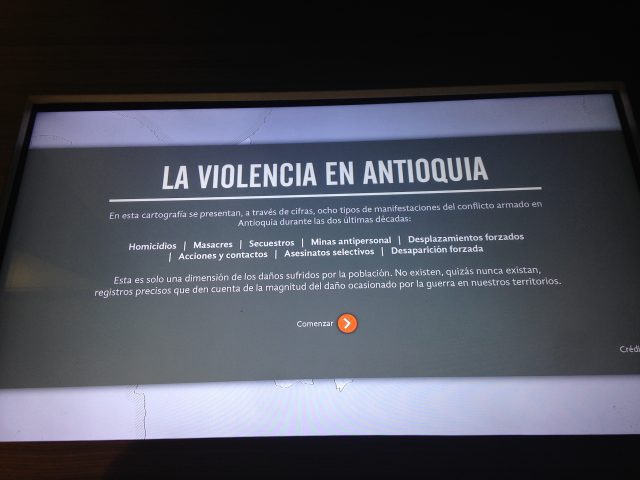

The permanent exhibition of the museum is divided into 16 topics. The first one, named Absences, opens the hall with a mirror wall in which people can read fragments of testimonies related to the sadness of losing loved ones, homes, lands, and domestic animals. The second one, Nostalgic Landscapes, is an audiovisual projected on a wall in which one can observe Antioquia’s rural sceneries affected by the armed conflict. It is meant to convey the pain of forced displacement. The third one, called simply Medellín, is a narrative of the city’s history since 1541. It includes indigenous peoples, afrodescendants, and peasants, trying to be as inclusive as possible. The fourth, Sensitive Territories, is composed by three interactive cartographies which show the numbers of the department´s municipalities, facts of victimization that are remembered collectively, and memory sites in Medellín. These cartographies are intended to highlight how the people from Antioquia resisted the conflict, to denounce atrocities, and to call the viewers’ attention to social mobility.

Interactive Cartographies. People can touch the screens and navigate through information related to violence, victims, and memory (Jimena Perry, 2017).

The fifth space is called Medellín in Movement. It is also a video in which spectators can see the city in action. It shows streets, people, activities, traffic, day, night, and the different ways of inhabiting the urban center. The sixth one, Children’s Words, is a touching panel in which kids define words such as love, violence, fear, dead, displacement, and murder. This is one example: “Murder: To take away the best of a person.” This sentence was written by a nine-year-old boy. The seventh, is an interactive chronology, from 1946 to 2013, in which the history of Colombian violence is told. This piece sticks out due to its grand size and the information it contains. A person can click on its links to find out specific data about certain events, such as the creation of the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC-EP (Armed Revolutionary Forces of Colombia-People’s Army), peace processes, and institutional efforts to end the country’s armed conflict.

Space number eight is perhaps one of the most impressive of the displays. It is called Multiple Faces of Violence. This is a sample of approximately 50 pictures taken by four known photographers. The images are displayed in triptychs which the observer can turn and alternate. They are shocking and capture many violent moments that deserve reflection. Besides the pictures there is an interactive screen where the photographers tell their experiences taking the images. The following pictures are the work of Natalia Botero, Jesús Abad Colorado, Albeiro Lopera and Steven Ferry. I chose only a few of them. The images reproduced here were taken by Jimena Perry.

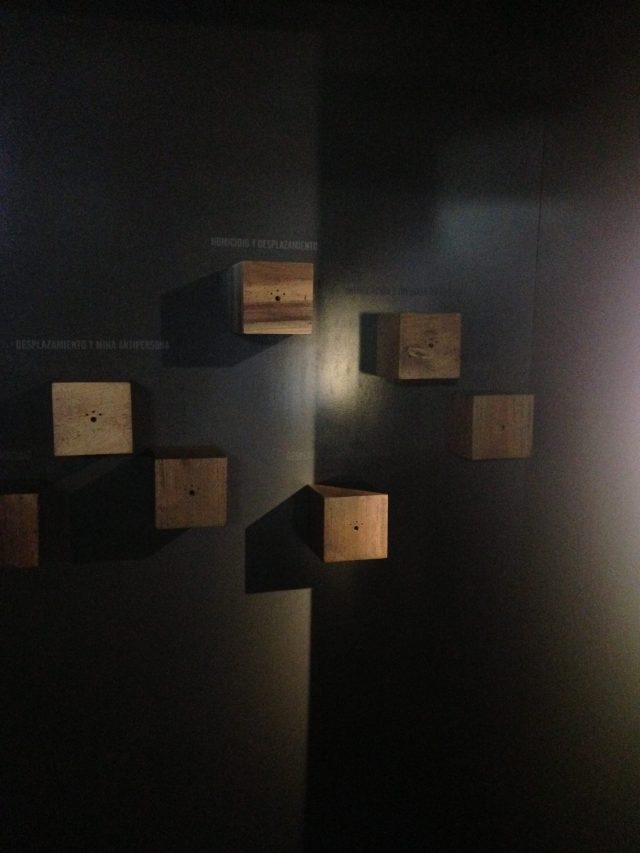

The ninth topic of the permanent exhibition is named Words. Like with the children’s definitions, here children and adults play with the meanings of fear, solidarity, resiliency, memory and difference. The tenth space, Whispers, as shocking or more as the former, is composed by 13 wooden boxes attached to a wall. If someone places his or her ear to a box, a testimony of violence can be heard. The narrative of each box is different and some of them are very hard to listen to.

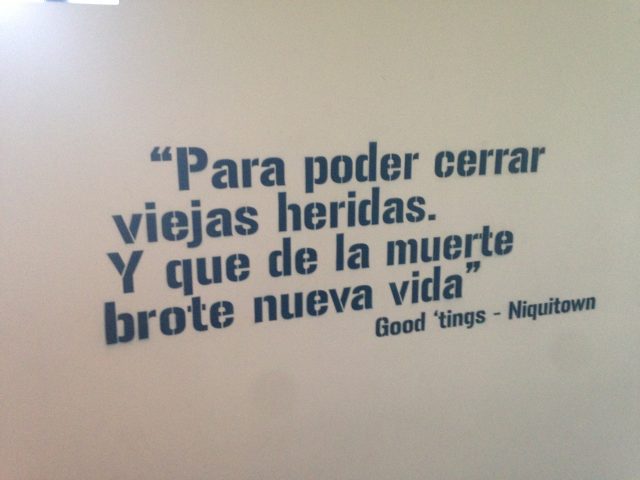

The eleventh space is a composition of 16 cases with artistic pieces in which the armed conflict is represented. They are in the middle of the permanent hall and include topics such as violence against the earth and indigenous communities. The twelfth one, Present Histories, is made of three person-size panels in which recent victims — survivors of violence, politicians, activists of human rights, and priests — give their views and experiences of war. Twenty-four different voices can be heard here. Space thirteen is a recompilation of recent songs with social meaning. Here people can stop to listen to the music, which is mainly hip-hop and rap. The fourteenth one, Art’s Point of View, is also an interactive panel that presents artistic works in which violence is depicted. The fifteenth one, Memory Enclosure, is a wall in which the viewer observes images that come and go over a black screen. The pictures allude to birthdays, baptisms, and everyday life activities and chores to remind the viewer how life was interrupted violently. The last part of the permanent exhibition is a long hall in which there are fragments of speeches of human rights activists, writers, and other people who had fought for peace in Colombia.

Medellín’s House-Memory Museum is a place intended to give voice to Medellín’s victims of violence and provide them a site to grieve, reunite, remember, and develop strategies to avoid future violence. The institution’s first director defined this mission clearly enough, however the second and current one is implementing some changes. She said publicly that the museum should not only be for victims and perpetrators but for every citizen. This statement caused uneasiness in the city’s inhabitants because the space is supposed to represent symbolically the people directly affected by violence. So, here big questions come up: How much inclusion is desirable? Which is the audience of the institution?

Another issue worth mentioning is the absence of drug trafficking victims at the museum. Even though Pablo Escobar was born in Rionegro, his business was all run in the capital of Antioquia. Escobar and his organization, the Medellín Cartel, committed 623 attacks that left hundreds of dead civilians and thousands wounded. The Cartel also was responsible for the murder of 550 policemen, 100 bombs in Bogotá and Medellín in malls, official institutions, airplanes, and newspapers. Approximately 15,000 people died due to the actions of the Medellín Cartel between 1989 and 1993. Among the deceased were presidential candidates, journalists and politicians. Kidnappings of politicians and journalists were very common as well. It is surprising that the museum does not mention these victims. This is a part of Colombian history that remains absent from most institutions, drug lords are not part of museum narratives leaving big silences that need to be filled. Perhaps telling this part of history should also be part of the healing process.

![]()

Also by Jimena Perry on Not Even Past:

Time to Remember: Violence in Museums and Memory in Colombia, 2000-2014

My Cocaine Museum, by Michael Taussig (2004)

You may also like:

Magical Realism on Drugs: Colombian History in Netflix’s Narcos

![]()

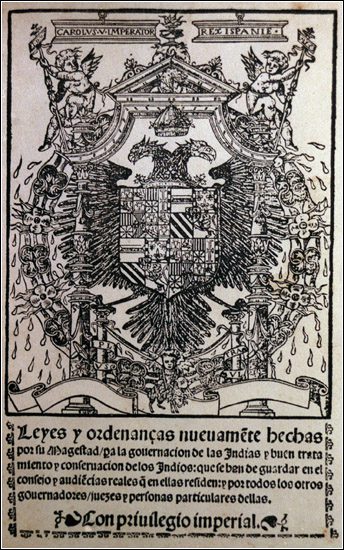

Subjugating and Christianizing these unincorporated indigenous peoples, called bárbaros (translated as “savages”) were major objectives of late eighteenth-century Bourbon reforms. David Weber concludes that “pragmatism and power usually prevailed over ideas,” with Bourbon policy usually favoring a realistic approach to dealing with these native groups, alternatively using armed conflict or negotiation when each seemed most useful. The Spanish crown was only one of several interest groups—including Bourbon officials, the military, and the colonial bureaucracy—competing for the loyalty of indigenous peoples. Indians from geographically disparate Spanish borderland regions had more in common socially and culturally with each other than with the inhabitants of nearby colonial centers, like Mexico City or Lima. Weber justifies the range of his study by contending that others have looked at Spanish and native relations only from a local perspective, failing to account for the diverse challenges these groups posed for Bourbon rulers.

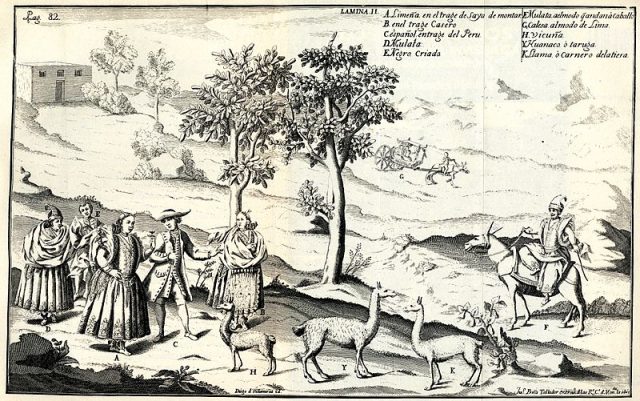

Subjugating and Christianizing these unincorporated indigenous peoples, called bárbaros (translated as “savages”) were major objectives of late eighteenth-century Bourbon reforms. David Weber concludes that “pragmatism and power usually prevailed over ideas,” with Bourbon policy usually favoring a realistic approach to dealing with these native groups, alternatively using armed conflict or negotiation when each seemed most useful. The Spanish crown was only one of several interest groups—including Bourbon officials, the military, and the colonial bureaucracy—competing for the loyalty of indigenous peoples. Indians from geographically disparate Spanish borderland regions had more in common socially and culturally with each other than with the inhabitants of nearby colonial centers, like Mexico City or Lima. Weber justifies the range of his study by contending that others have looked at Spanish and native relations only from a local perspective, failing to account for the diverse challenges these groups posed for Bourbon rulers. Weber analyzes these Indian societies based on how they defended their independence, rather than grouping them by geography. Yet, on the imperial periphery, cooperation and integration often came before conflict. Weber contends that the incompatibility between Spaniard and native was not as pronounced as other scholars have claimed. One successful tactic the Bourbons used to integrate native populations without open conflict was by taking over the independent missionaries, especially Jesuits, that operated in many peripheral areas. The book concludes by tracing the story of the indios bárbaros into the national period, a time in which the leaders of the new republics abandoned old Bourbon policies of negotiation. They came to regard independent natives as inferior peoples, and, in Argentina, the most radical case, actively exterminated the indigenous population.

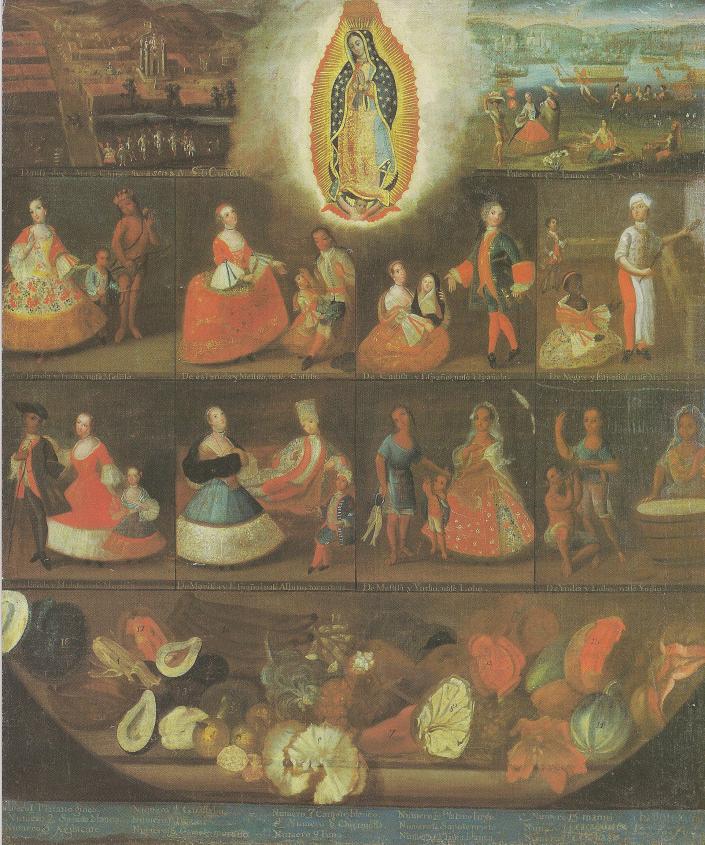

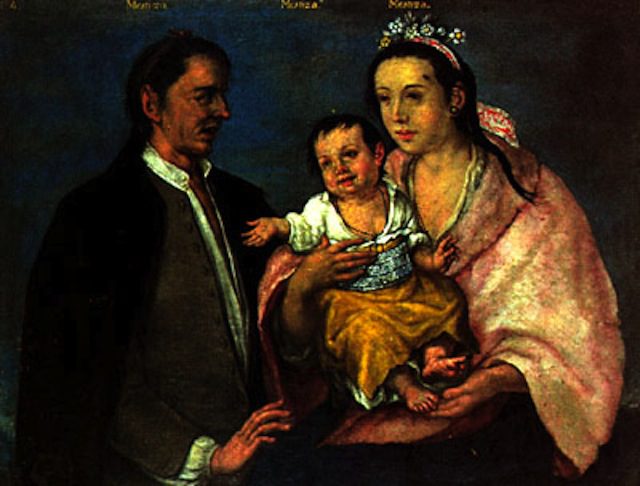

Weber analyzes these Indian societies based on how they defended their independence, rather than grouping them by geography. Yet, on the imperial periphery, cooperation and integration often came before conflict. Weber contends that the incompatibility between Spaniard and native was not as pronounced as other scholars have claimed. One successful tactic the Bourbons used to integrate native populations without open conflict was by taking over the independent missionaries, especially Jesuits, that operated in many peripheral areas. The book concludes by tracing the story of the indios bárbaros into the national period, a time in which the leaders of the new republics abandoned old Bourbon policies of negotiation. They came to regard independent natives as inferior peoples, and, in Argentina, the most radical case, actively exterminated the indigenous population. Cope overturned the idea that racial identity in colonial Mexico was “fixed permanently at birth” and argued that race was a versatile identity that could be “reaffirmed, modified, manipulated, or perhaps even rejected.” The unfixed nature of identities assumed and performed by individuals and groups in colonial Latin America beyond Mexico City is the subject of the collection of essays edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara recently published as Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.

Cope overturned the idea that racial identity in colonial Mexico was “fixed permanently at birth” and argued that race was a versatile identity that could be “reaffirmed, modified, manipulated, or perhaps even rejected.” The unfixed nature of identities assumed and performed by individuals and groups in colonial Latin America beyond Mexico City is the subject of the collection of essays edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara recently published as Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.