Scholars of the modern Middle East have long identified the region’s integration into the global economy as one of the most dramatic processes of the nineteenth century. Two recent studies – Aaron Jakes’ Egypt’s Occupation: Colonial Economism and the Crises of Capitalism and On Barak’s Powering Empire: how Coal Made the Middle East and Sparked Global Carbonization, draw on this tradition and push us beyond the traditional economic narrative to consider some wider cultural contexts. While different in scope, scale, and methodological choices, combining the two books together prompts readers to think more broadly about both the Middle East and the historical moment of the nineteenth century.

Aaron Jakes’ Egypt’s Occupation is a detailed study of the materiality of British colonialism in Egypt between 1882 and 1914. The book frames the British colonial project as one driven by economism – the assumption that certain societies are predestined to operate according to distinctive economic logic. Contrary to past narratives of modern Egypt that centered around large landowners, Jakes places the Egyptian peasant (fellah) as the main protagonist of the colonial story. British officials imagined the fellah as an economic actor that, while motivated by the pursuit of greater profits, remained inherently incapable of grasping the logic of the modern liberal economy. Materially, the logic of colonial economism unfolded in the creation of various financial institutions designed to support the individual fellah. This logic not only limited Egypt’s economic growth but also served as proof to the British that Egypt needed the occupation to move toward modernity. Needless to say, in the eyes of British officials, Egyptian modernity was ambiguously defined as it was inherently unreachable.

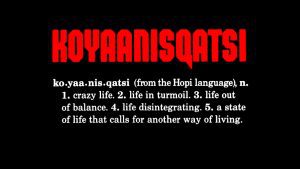

Jakes narrative concentrates on the Egyptian case to make a broader argument about capitalism. Unlike Jakes, On Barak’s Powering Empire stretches across and beyond the region and begins with an intriguing proposition: to understand our hyper-carbonized moment and begin imagining a carbon-neutral future, Barak suggests studying how fossil fuels – and especially coal – became a global commodity. Contrary to common narratives that focus on Europe, and especially Britain, as the epicenter of the rapid carbonization of the nineteenth century, Barak suggests the Ottoman empire as the space in which coal became widely consumed, traded, and utilized to various needs. Barak urges the readers to think about coal, and fossil energy more broadly, as one crucial element in a complex historical and cultural context. Coal was the driving force behind vast social changes. It allowed cooling systems that enabled better storage of meat and raised meat consumption popularity; it made trains faster and more common, changing in the process how people in the region moved; and it helped pump water and allowed new irrigation methods that transformed local agricultural techniques. Coal, in short, became popular because it was mobile, cheap, and efficient. Unfortunately, we all breath the results of this efficiency to this day.

While different in geographical focus, these two thought-provoking works complement each other while opening up important debates. One such contribution is their emphasis on the importance of the Middle East region to some of the global processes of the nineteenth century. Barak, for example, draws on Kenneth Pomeranz’s The Great Divergence to argue for the region’s importance as a bridge between Europe and Asia (p. 9-10). Jakes, for his part, suggests Egypt’s cotton market as another case study with which to rethink the spread and perseverance of capitalism. Bringing together the rich historiography that evolved around cotton production in Egypt with new studies of capitalism and nature, Jakes uses hyper-local developments such as irrigation systems and credit institutions to support Jason Moore’s call to see capitalism as a “way of organizing nature” (p. 12-13).

Emphasizing the significance of the region to the global transformation of the nineteenth century, both scholars contribute to the decolonization of two contemporary conversations. Jakes’ work is highly influenced by the new history of capitalism – a relatively fresh interpretational framework that asks to rethink capitalism beyond traditional Marxist traditions. This new field usually revolves around the American capitalist experience, and as such is organized around challenging old perceptions regarding, among else, capitalism’s connection to slavery, American exceptionalism, and westward expansion. Jakes, for his part, uses the field’s preoccupation with financial institutions and commodities to place the Egyptian case not in comparison to the US but rather to India, where many of his colonial protagonists began their careers. This is a promising move that will potentially contribute not only to the inclusion of nonwestern case studies in this new tradition but also bring the latter into conversation with Middle East studies.

Similar to Jakes’ aspirational project, Barak clearly states that one of the main goals of his book is to rethink the European origins of energy history, or, in his words, to “provincialize thermodynamics” (p. 229). To do so, Barak offers some impressive geographical maneuvers: first, he situates Europe not at the center of his argument, but rather almost at the periphery of the greater drama of energy production and consumption that took over the Middle East. He elegantly intertwines large scale spatial changes in trade and commerce roots with micro-changes in urban development and coal-mine structures. In doing so, he reveals an interconnected world that exists outside of and independently from Europe. This is not to say that Barak neglects the global in favor of the local. On the contrary, transregional connections enable his narrative to move forward. For example, he takes on Timothy Mitchell’s now-famous argument about the positive correlation between fossil energy and democratic organizations, what Mitchell calls “carbon democracy.” Barak, on the other hand, stress how workers’ rights in Europe were achieved “on the backs of colonial workers” (p. 115), thus proving that carbon democracy in one place remains desperately dependent on the existence of carbon autocracy elsewhere.

Finally, both works’ unconventional intervention in commodity history makes them appealing to readers outside the narrow field of Middle East scholars. While both examine two of the most “popular” commodities of the region – cotton and fossil fuel – they successfully created narratives that places these two commodities in a deep cultural context rather than the “traditional” economic-oriented analysis. Some may argue that the authors often overlook the material qualities of these commodities. However, I see their attitudes as an opportunity for scholars to rethink their commodity-driven narratives. Barak, traces how the expansion of the coal trade and increased consumption habits altered the everyday lives of local communities. In his discussion of meat consumption and meat’s political role (chapter 2), he urges the readers to think about meat not only as a commodity or a cultural artifact but also as an energy source. Through this intervention, he helps bring food history and energy history to the same table in what is a promising conceptual novelty.

Similarly, Jakes leans on a rich historiographical tradition that underlines the importance of cotton cultivation to economic growth in nineteenth-century Egypt and links it with new conversations. His elaborate discussion about cotton (chapters 3 and 7) explores the commodification of land and the fight against the cotton-leaf worm and connects the debate about cotton to larger conversations about legal reforms, agronomy, expertise, and environment. While some environmental historians might criticize him for not delving more deeply into the complexities of the nature/culture dichotomy and the environmental consequences of expanding cotton production, other works address this issue. I direct readers especially to Jenifer Derr’s The Live Nile (2019), which can be read as a complementary work. In any case, they (and others) will appreciate Jakes’ impressive empirical achievements in documenting changing land tenures and credit systems.

What makes these works noteworthy is their ability to talk to a wide range of readers and be interesting and deep at the same time. Scholars of the modern Middle East will surely benefit from their empirical richness and from their unique contribution to rethinking the geography of the region. At the same time, readers from outside of the field will find two fascinating, accessible, and inspiring works. Their conceptual innovation and contribution will make them staple readings for environmental historians, historians of science and technology, and curious readers.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.