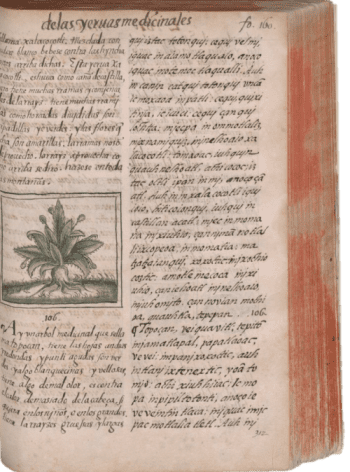

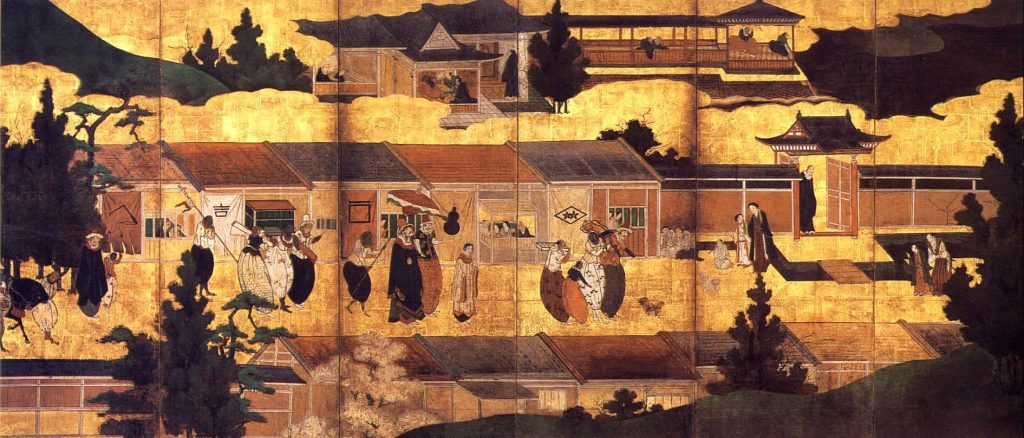

(via Wikimedia Commons)

This series features five online museum exhibits created by undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin for a class titled “Colonial Latin America Through Objects.” The class assumes that Latin America was never a continent onto itself. The course also insists that objects document the nature of historical change in ways written archives alone cannot.

John Monsour’s exhibit on Nanban screenfolds exemplify the deep connections of the colonial Americas to early-modern Japan. Portuguese Jesuits and merchants arrived in southern Japan in the mid-sixteenth century with commodities from India, Europe, and the Americas and with hundreds of Luso-Africans. The foreigners were called “Nanban” (barbarians from the south). The Jesuits gained a foothold with Japanese lords that led to the massive conversions of commoners and nobles. Jesuits and Japanese artisan established workshops that produced many Nanban objects, including screenfolds documenting new European cosmographies. The maps also document the introduction of Chinese-Korean maps. Monsour’s exhibit shows the maps on Edo workshops led by Jesuit and the new cosmographies they engendered.

More from the Colonial Latin America Through Objects series:

Of Merchants and Nature by Diana Heredia López

You may also like:

Brittany Erwin reviews The Archaeology and History of Colonial Mexico by Enrique Rodriguez Alegría

Acapulco-Manila: the Galleon, Asia, and Latin America, 1565-1815 by Kristie Flannery

Purchasing Whiteness: Race and Status in Colonial Latin America by Ann Twinam